DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Centre for Civic Engagement.

Canadians witnessed an unusual spectacle in November 2021: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Alberta Premier Jason Kenney making a joint policy announcement. The Liberal prime minister and Conservative premier had long been political enemies, yet there they were, giving a COVID-era “elbow bump” and (nearly) putting aside their political differences to sign a $3.8 billion agreement to bring $10-a-day childcare to Alberta.

By March 2022, every province and territory signed a bilateral childcare agreement with the federal government, which earmarked $27 billion over five years to achieve $10-a-day childcare across the country. In 2025, every province and territory except Alberta and Saskatchewan agreed in principle to sign on for five more years. Federally subsidized childcare has become part of the Canadian policy architecture, having already outlived the political tenures of Trudeau and Kenney.

More than four years after the first bilateral agreement was signed, this DeepDive explores these agreements’ effect on the Canadian childcare landscape. While fees have been reduced for families lucky enough to secure a regulated space, the agreements have contributed to swelling waitlists as most jurisdictions have failed to meet their space creation targets. By favouring credentialized workers and not-for-profit providers, the federal government’s childcare policy has contributed to policy inflexibility and accelerated the shift away from home care and towards centre-based care. As the promise of $10-a-day care has collided with limited supply, the price tag for governments will only increase.

The slow march to a national childcare framework

For decades, Canadian activists and childcare scholars (often the same people) persistently but unsuccessfully sought a national childcare policy. Yet due to provincial jurisdiction over childcare, the federal government’s role was, until recently, primarily limited to indirectly funding childcare through block grants like the Canada Social Transfer, tax credits for childcare expenses, and directly sending “child benefit” money to parents.

The victory of child benefits over a national childcare system was cemented in the 2006 federal election, when Liberal director of communications Scott Reid apologized after saying the Conservatives’ proposed child allowance would allow parents to “blow” the money on “beer and popcorn.” Although childcare policy “experts” uniformly supported the Liberals’ plan for a national childcare program, Stephen Harper’s rebuttal—“There are already millions of childcare experts in this country. Their names are Mom and Dad”—effectively settled the debate for a generation. After winning the 2015 election, the Trudeau government moved quickly to expand Harper’s cash benefits into the Canada Child Benefit while dragging its feet on a national childcare policy.

The Trudeau government’s policy changed—first slowly, then all at once—around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Freed from the (already limited) pre-COVID fiscal restraints, between 2021 and 2022, the Trudeau government signed bilateral agreements with every province and territory to create the Canada-wide Early Learning and Child Care framework (CWELCC, pronounced “kwelk”).

In 2024, Parliament passed An Act Respecting Early Learning and Child Care in Canada, which set out principles to maintain long-term childcare funding for provinces and Indigenous Peoples. Then, one week before he left office, Trudeau reached agreements with every province and territory except Alberta and Saskatchewan to spend an additional $36.8 billion to extend CWELCC for five more years (Ontario signed an in-principle extension but has not yet formally signed its agreement).

The federal government has modelled its desired policy on Quebec’s childcare system, which has had fixed fees for publicly-subsidized childcare since the 1990s (initially $5/day, now $9.35/day). Because Quebec’s system was deemed to have already accomplished the goals in CWELCC, Quebec’s initial “asymmetrical” agreement with the federal government involved an unconditional transfer of $6 billion, and it will receive an additional $9.8 billion over the next five years. For the remaining provinces, the bilateral agreements are conditional on working towards targets related to fees, spaces, and credentialization.

Children are comforted as they play at the Blessed Chiara Badano Child Care Centre in Stouffville, Ont., Friday, May 2, 2025. Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press.

The impact of CWELCC: Fees, spaces, and credentialization

Federal and provincial childcare policies relate to three types of pre-Kindergarten care: centre-based care, primarily daycare centres and preschools; licensed home care, where a caregiver provides for children in their home in accordance with provincial regulations; and unlicensed home care, where the caregiver is subject to more minimal standards (in Ontario, these mainly concern the number of children in the home). In 2023, 56 percent of children aged 0 to 5 were in some form of licensed or unlicensed childcare, an increase from 2020 (52 percent) but still below pre-pandemic levels of 60 percent in 2019.

With respect to childcare, governments in Canada tend to do three things: run it (rarely), fund it (increasingly), and regulate it (almost always). Canadian childcare is not typically run by governments: in 2022, 51 percent of childcare centres were private, while 49 percent were “not-for-profit or government-run.” While Statistics Canada does not provide a breakdown between the “not-for-profit or government-run” category, most of these centres have traditionally been run by non-profits, not governments (unlike in Sweden or France).

The CWELCC bilateral agreements have shifted the way childcare is both funded and regulated. Under CWELCC, the federal government contributes funding to provincial childcare systems, as provinces send funds to childcare centres, home care providers, home-care agencies, and municipalities. For licensed (regulated) childcare centres and home care providers, parents pay a fixed fee, with the rest of the cost subsidized by government. CWELCC does not apply to unregulated home care providers, to whom parents must pay the full (unsubsidized) cost.

By virtue of this funding, CWELCC has enabled the federal government to create goals that influence how provinces regulate childcare. After analyzing the many federal frameworks, backgrounders, and bilateral agreements, I have identified six distinct goals that inform the CWELCC framework:

- Affordability: Bring the costs of childcare down to $10-a-day.

- Accessibility: Increase the number and percentage of children in childcare.

- Flexibility: Make childcare available to parents working non-traditional hours and tailored to different provincial and territorial needs.

- Inclusion: Make childcare available to children with varying abilities and who are experiencing vulnerability.

- High-Quality: Ensure learning is delivered by a qualified and trained workforce.

- Indigenous-led: Ensure Indigenous childcare is led by Indigenous Peoples and informed by Indigenous knowledge, culture, and languages.

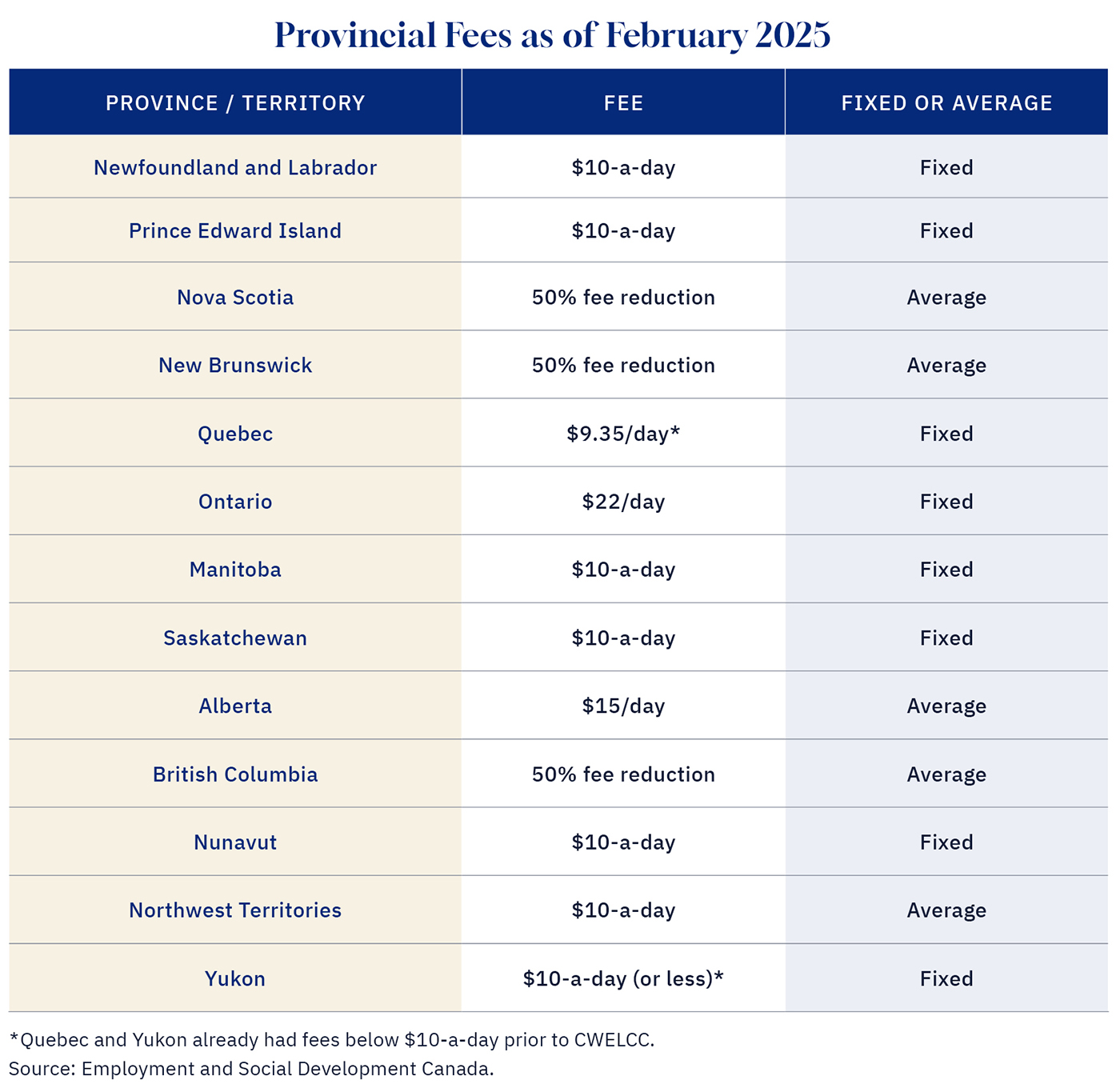

The most prominent goal of the bilateral agreements is affordability, by bringing parental fees for regulated care down to $10-a-day by 2025/26. The federal government claims that eight of the 13 provinces and territories had met this goal as of February 2025 (though one childcare research agency pegged the number at six, not eight), while “all other jurisdictions have reduced parent fees by at least 50%.”

As the table below shows, Ontario’s $22/day rate—which, full disclosure, I am currently paying—is the outlier among provinces with a fixed rate (Ontario’s Auditor General estimated it would cost an extra $2 billion a year to get down to $10/day). CWELCC has almost certainly contributed to a reduction in the average fees parents pay for full-time childcare, which, according to Statistics Canada, decreased from $649 to $544 a month between 2022 and 2023.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

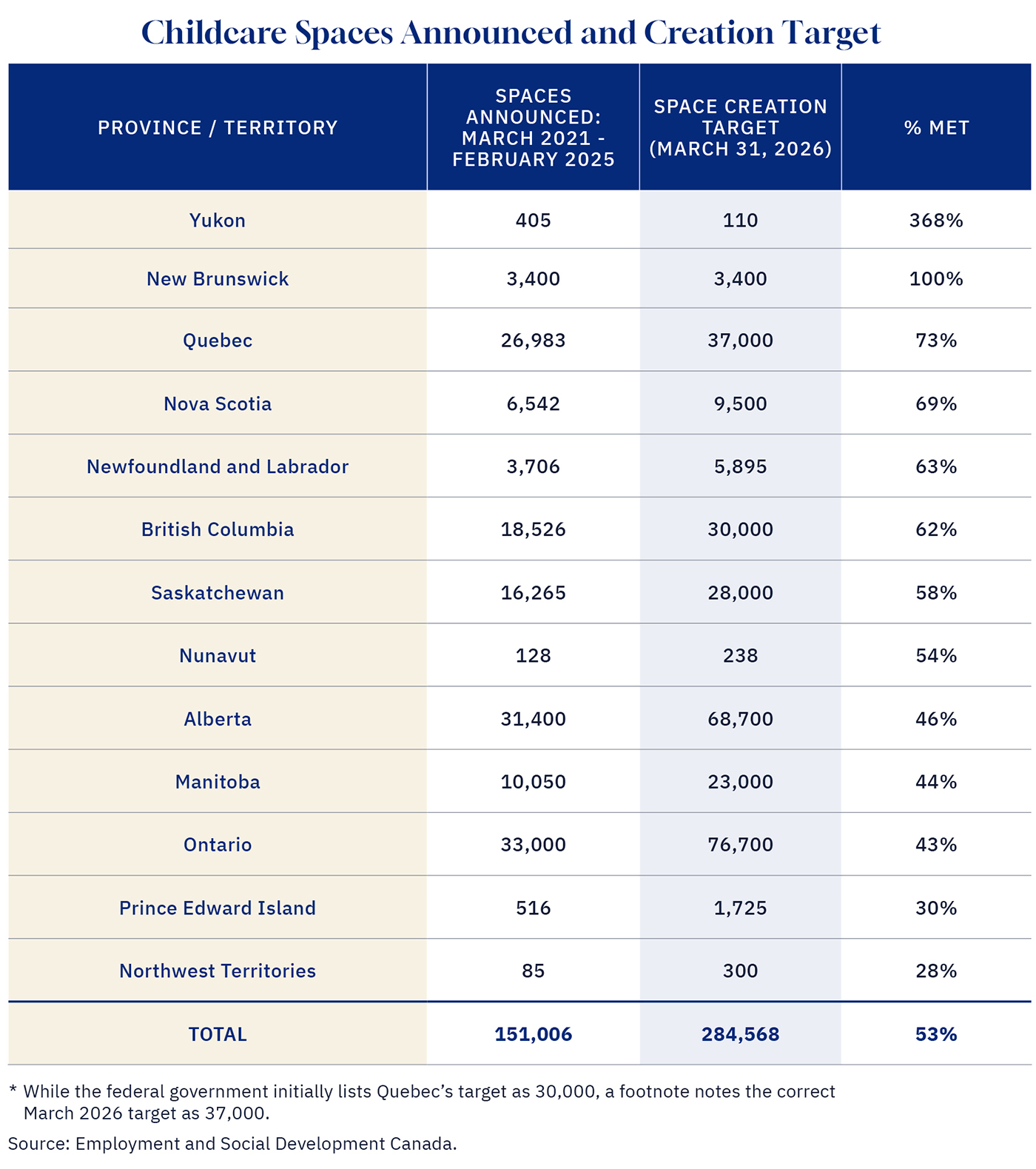

The CWELCC agreements also specify jurisdiction-specific “space creation targets” for more than 250,000 new childcare spaces by March 2026. While individual agreements make allowances for some for-profit spaces, they tend to emphasize that spaces created should be “predominantly” or “primarily” in not-for-profit centres or licensed home care.

Earlier this year, the federal government provided an update on the “spaces announced” since 2021. With the caveat that the government’s figures rely on shifting definitions—this number only includes “announced measures to create” new spaces, which does little good to a parent on a waitlist—the table below compares these announced spaces to each jurisdiction’s space creation target. Because these data were from February 2025 (47 of 60 months into the federal timeline), any jurisdiction above 78 percent is, in theory, on track to meet its target. However, as of February 2025, only Yukon and New Brunswick had met their space announcement/creation goals, with Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, PEI, and the Northwest Territories below 50 percent of their target.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Through the bilateral agreements, the federal government has clearly linked the goal of “high-quality” care to credentialized staff such as Early Childhood Educators (ECEs) and Child Care Assistants (CCAs). The agreements include targets to train and hire more childcare workers through aspects such as a minimum wage grid employees, funding for curriculum re-development, and tuition reimbursement.

Critics have noted how this credentialization of childcare has crowded out the supply of non-credentialed childcare, further contributing to a cramped labour market for childcare providers. Statistics Canada data from 2024 show that more than 86 percent of child care centres reported “experiencing difficulties when trying to fill vacant positions”; the most common difficulties were “applicants’ lack of skills required for the job (66.7%), having few or no applicants to choose from (62.3%) and applicants’ lack of related work experience (53.3%).”

The shift towards centre-based care

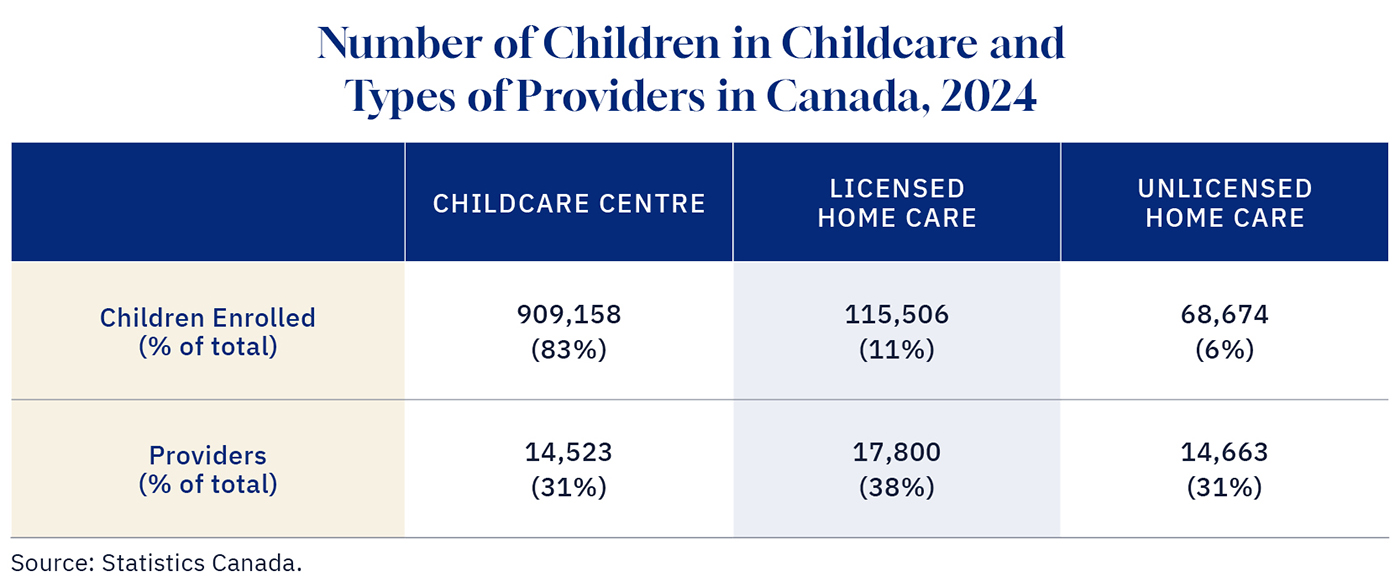

Although CWELCC subsidies are available for licensed centre- and home-based care, the post-CWELCC era has coincided with a shift away from home care. The table below, using Statistics Canada data from 2024, shows that the vast majority of children in childcare (83 percent) were in a centre rather than a home. Of those in home-based care, 63 percent were in licensed care, with 37 percent in unlicensed care. While unlicensed homes are ineligible for CWELCC funding, it is unclear precisely how many licensed homes received funding; according to Statistics Canada, only 36 percent of licensed homes across Canada had confirmed receiving CWELCC funding compared to 36 percent who had not, with 29 percent unknown.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

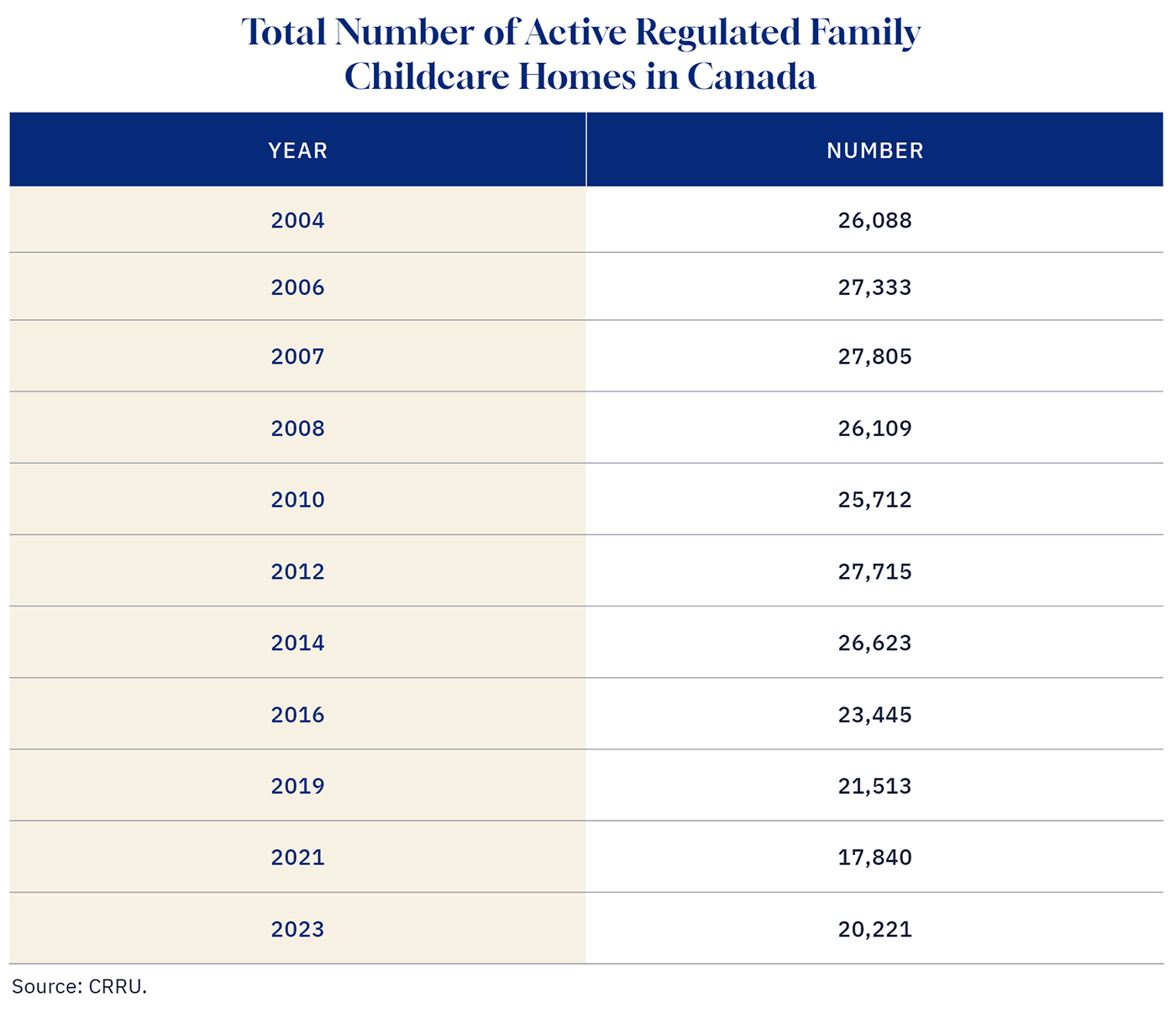

The table below shows that there has been a steady decrease in the number of regulated (licensed) childcare homes since 2012, well before CWELCC began. Part of the drop between 2019 and 2021 was due to the COVID-19 pandemic; during those years, there were “477 fewer centres and 3,673 fewer active family child care homes.”

However, the post-pandemic (and post-CWELCC) period has seen a movement away from all forms of home-based care. Between 2019 and 2023, Statistics Canada reported a growth in the proportion of children aged 0-5 who were in centre-based child care, from 31.0 percent to 34.3 percent. By contrast, during this same period, the proportion of children in home-based care declined from 12.2 percent to 9 percent—a drop of more than one quarter. This period also saw a large decline in the proportion of children who were cared for by a non-relative in the child’s home (such as a nanny), from 3.0 percent of all children to 2.1 percent.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

CWELCC’s desired “flexibility” has also not come to fruition. On the one hand, unlicensed home care providers were the most likely to provide “flexible care” (overnight, evenings, and weekends) for parents, with 17 percent compared to 11 percent of centres and 5 percent of licensed homes.

On the other hand, much of this “flexible care” will soon be disappearing: nearly 43 percent of unlicensed home care providers “reported not intending to continue providing child care services in their home in three years,” compared with just over 16 percent of licensed home care providers. While CWELCC may not be the sole cause, its emphasis on credentialized care has coincided with a growth in childcare centres and a decline in home-based childcare, especially unlicensed care.

Finally, the CWELCC era has also seen a sharp rise in the number of parents on childcare waitlists. The supply of childcare spaces has failed to keep up with CWELCC’s subsidy-induced demand: in 2023, among parents of children aged 0-5 who were not using childcare, 26 percent had their child on a waitlist, compared to only 19 percent in 2022. For parents of infants under 1, the number was a staggering 47 percent, with reports of parents putting unborn children on waitlists. Statistics Canada’s 2024 survey of childcare providers found that 77 percent of centres had a waitlist, compared with 62 percent of licensed homes and 38 percent of unlicensed homes. Most venues were operating at maximum capacity, including 60 percent of centres, 81 percent of licensed homes, and 76 percent of unlicensed homes.

Canadian childcare policy’s shifting Overton Window

My undergraduates are often surprised to learn that there are serious debates about whether the federal government should be involved in childcare policy. I believe there are two reasons why. First, most prominent Canadian childcare scholars and policy experts are themselves strong advocates for a more expansive federal role in the funding, regulation, and provision of childcare. One of the main sources of childcare data, the Childcare Resource and Research Unit, describes its mandate as working “towards an equitable, high quality, publicly funded, inclusive early learning and child care (ELCC) system for all Canadians.” There is little sustained criticism of a national, subsidized childcare system outside of The Hub, the National Post, or Cardus; there is essentially none within Canadian academia. With advocacy and scholarship so intertwined, Chrystia Freeland’s claim that “early learning and childcare is an investment in social infrastructure that pays for itself” is often taken as a given by students and professors alike.

Second, childcare activists have decisively won the political debate. CWELCC agreements were signed with every province, including those governed by conservatives; while Alberta, Saskatchewan, and (formally) Ontario have held out on signing new agreements, it is difficult to see them turning down additional federal money in the long run. The 2025 federal Liberal platform vowed to “protect and strengthen” the CWELCC system and to “Require provinces, territories, and municipalities to expand child care in public infrastructure.” Federal Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has criticized the program’s implementation and promised to loosen restrictions on for-profit funding, but has said he would honour existing agreements. Perhaps most importantly, Canada’s national childcare policy remains popular, with a YMCA-commissioned survey finding 68 percent national support just last month.

At the political level, there is no longer a question of whether the federal government should be involved in childcare funding and standard-setting. Instead, political debates primarily concern how much and to what extent, such as whether more CWELCC funding can be given to for-profit centres. And although critics have convincingly argued that a flat $10-a-day fee disproportionately helps wealthy parents (who are more likely to work 9-5 jobs and have the resources to navigate the waitlist bureaucracy), Alberta’s pleas for a more means-tested system have fallen on deaf federal ears. The goal of $10-a-day childcare appears politically untouchable for now.

Children’s backpacks and shoes are seen at a daycare franchise, in Langley, B.C., on May 29, 2018. Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press.

In this policy context, there are nevertheless potential reforms that could realistically increase the supply of childcare spaces. One reform would be to reduce the reliance on labour credentials that have been so ingrained into CWELCC agreements. As Ginny Roth has noted in The Hub, it has never been adequately explained “why Early Childhood Educator, a designation that didn’t even exist in Ontario until 2007, is the pinnacle of quality care.”

A second reform would be to permit more funding to for-profit centres. CWELCC frameworks prioritize non-profit space creation and typically lock in a maximum proportion of funds for for-profit spaces. This squeezes out (primarily female) entrepreneurs and further constrains supply. However, because CWELCC agreements do fund some for-profit spaces—as well as licensed home care providers, who profit from their labour—the expansion of for-profit spaces under new agreements should be politically feasible (indeed, even the Quebec government has funded more for-profit daycares in recent years).

A major sticking point for both these reforms is that childcare activists vehemently oppose for-profit care nearly as much as they support childcare credentialization (and, unsurprisingly, unionization). However, sustained pressure from governments such as Alberta and Ontario, particularly concerning for-profit care, could help bring about reform and increase supply. Most parents would agree that a spot at a for-profit centre—or with a non-credentialed caregiver—is certainly better than a spot on a waitlist.

Key takeaways

Several conclusions can be drawn about the implementation of Canada’s national childcare framework:

- The framework has received widespread buy-in from provincial and territorial governments, notwithstanding the current reluctance of Alberta and Saskatchewan to sign on to another five years.

- Fees have come down for parents who can get their child into a regulated space.

- Almost every province and territory is behind on their space creation targets.

- The agreements have sped along the credentialization of childcare, producing labour shortages and accelerating a shift away from unlicensed care, home care, and for-profit care towards a regulated centre-based model.

- This combination of capped fees, increased demand, and limited supply has led to growing waitlists.

This, for better or worse, is the new childcare policy status quo in Canada. How did we get here? I identify three main reasons. The first is sustained advocacy from the childcare community. Scholars and activists—often the same people—have spent decades championing a federally-funded childcare system that prioritizes not-for-profit care by credentialed workers. After decades of frustration, these scholar-activists changed the hearts and minds of policymakers, entrenching their vision and achieving widespread political consensus among federal, provincial, and territorial governments. Regardless of whether one agrees with its policy prescriptions, the perseverance of the childcare lobby has been impressive.

Second, the COVID-19 pandemic provided the impetus for more comprehensive government intervention in childcare. The combination of employment disruptions during lockdowns, families avoiding childcare to limit their exposure, and closures of childcare facilities brought the issue of childcare to the national agenda. Increased federal spending during the pandemic also removed expectations that the federal government would ever balance its budget, which made $27 billion over five years look like a drop in the bucket.

The third and final factor is the Trudeau government’s approach to federalism and spending more broadly. Justin Trudeau’s willingness to expand the use of the federal spending power into further areas of provincial jurisdiction, alongside his abandonment of any pretense of fiscal restraint once COVID began, made it possible to continue the ($31.5 billion annually and growing) Canada Child Benefit and create a national childcare framework. Likewise, Trudeau’s decision to seek individual bilateral agreements with provinces and territories in 2021 and 2022, rather than seek a unified comprehensive agreement, made it increasingly difficult for the holdout provinces to refuse the money, even when those governments didn’t agree with the strings attached.

In the end, a national, federally-funded childcare framework—even one clearly failing with respect to flexibility and accessibility—looks like it is here to stay. While there was once debate about whether the federal government should fund child benefits or childcare, a new political consensus has emerged that it should do both, regardless of the cost. Even in the forthcoming age of fiscal austerity, childcare will remain yet another area of provincial policy where federal requirements loom large.

Has the $10-a-day childcare promise truly benefited all Canadian families?

What are the unintended consequences of prioritizing credentialized childcare workers?

Given the challenges, is the national childcare framework sustainable in the long term?

Comments (3)

It’s disgusting to think we need to have government funded workers raise our children. We have so many reports, and studies indicating how bad this is for children, yet we persist. I don’t believe parents need assistance in raising their children, but if there must be funding given, then give it directly to the parents, not the system. We’ve seen the breakdown in our public school model with this mentality, don’t make the same mistake twice.