For many Canadians, it was hard to see Hudson’s Bay lock its doors for good. Those empty spaces are a reminder of the jobs and heritage that Canada lost with its closure.

But business closures like this are also a part of how economies grow. When companies fail to innovate or adapt, they make room for those that do. A steady flow of business openings and closings signals a dynamic economy—one where people and capital consistently move toward more productive and innovative businesses.

That idea was the foundation of what just earned Canadian economist Peter Howitt and co-author Philippe Aghion the Nobel Prize. Their 1992 paper showed just how central “creative destruction”—the process of old firms being replaced by new and growing ones— is to long-term prosperity.

Yet since they published their paper, Canada’s economy has grown less, not more, dynamic. Since the mid-1980s, when good data became available, the healthy churn of businesses has steadily declined. The slowdown leveled off in the mid-2000s but hasn’t reversed.

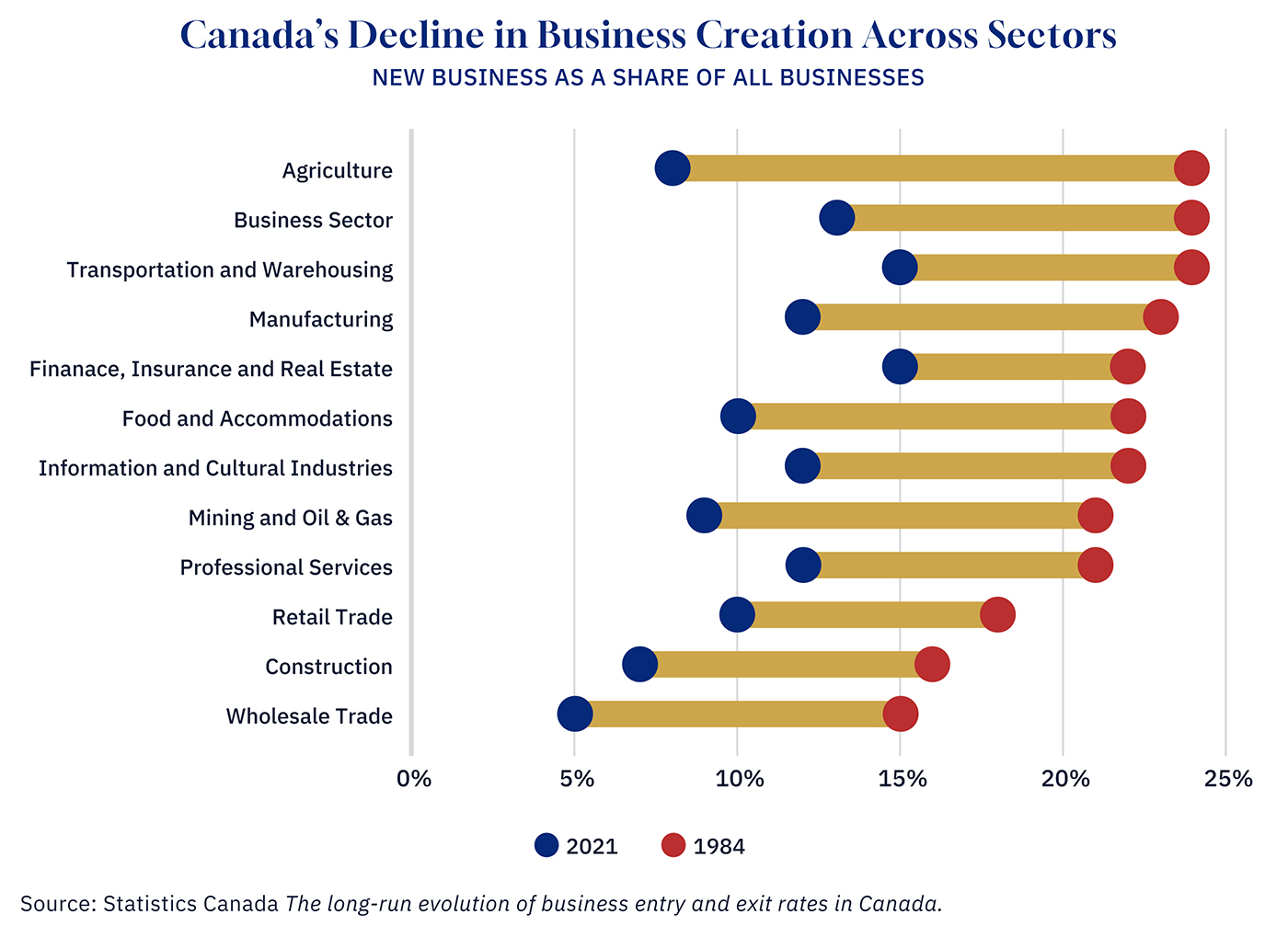

This isn’t just a Canadian issue. Business dynamism has collapsed across advanced economies. But the drop has been especially steep in Canada. While business turnover in the U.S. declined by 23 percent since the mid-1980s, Canada’s fell by 38 percent.

But while closures have also slowed, the bigger problem is the collapse in new business creation. Closures are down by about a quarter, but new openings are only half what they once were.

What’s behind this? Recent research rules out some plausible explanations. The decline isn’t confined to any one industry—manufacturing, retail, and services have all seen similar declines. Nor is it just a matter of market concentration. While telecoms and banking have become more dominated by a few big players, other less concentrated industries show the same trend. Meanwhile, the OECD’s Product Market Regulation index suggests that Canada has actually made progress in improving regulations to enhance competition over this period.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

There are, however, two other domestic factors that could help explain Canada’s sharper decline in new businesses.

The first is the country’s growing regulatory burden. Even if competition-related regulations have improved, the overall regulatory burden has undeniably increased. For entrepreneurs, that means higher costs and more red tape before a business can even get off the ground. One study estimates that added regulation has reduced new business entry rates by roughly 10 percent, and that’s just since 2006.

Second is Canada’s weak innovation ecosystem. Limited access to financing, poor policy incentives, and weak returns on R&D investments are a clear drag on innovation. These gaps prevent good ideas from turning into real products and businesses. While this has long been a disadvantage, it has likely become more problematic as innovation becomes more central to business creation and growth.

Building a more dynamic economy, where entrepreneurs are eager to take risks and enter new markets, needs to be a central focus for policymakers. After all, destruction without creation isn’t growth; it’s decline.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta. To learn more, read the commentary here.

How does 'creative destruction' relate to Canada's declining economic dynamism?

What are the two main domestic factors contributing to Canada's reduced business dynamism?

If business dynamism is crucial for long-term prosperity, what should policymakers prioritize?

Comments (0)