A recent video featuring Green Party Leader Elizabeth May—purportedly “debunking” Conservative MP Andrew Scheer on his criticism of the West Coast tanker ban—has been making the rounds online. In it, May delivers a compelling two-minute explainer for the impatient, complete with a hand-drawn coastline of British Columbia.

“Hello, lesson on geography and safe marine transit for oil tankers, especially to the attention of slow learners,” May said in the video.

Fact check: No, U.S. oil tankers do not pass through the Hecate Strait. @ElizabethMay shows exactly why the tanker ban exists, and why protecting it matters. pic.twitter.com/USzbQDYS1w

— Green Party of Canada (@CanadianGreens) November 21, 2025

But based on public records and local testimonies, her sweeping claims about tanker safety on B.C.’s North Coast appear to rely on outdated maritime imagery, selective geography, and overlook how modern commercial shipping actually works.

They imply that Canada could never safely ship oil out of a place like Prince Rupert, if a pipeline were to end there.

Here’s a breakdown of the key points.

Claim 1: Tankers would have to navigate the dangerous Hecate Strait

This is the foundation of May’s argument. It is misleading at best and incorrect at worst.

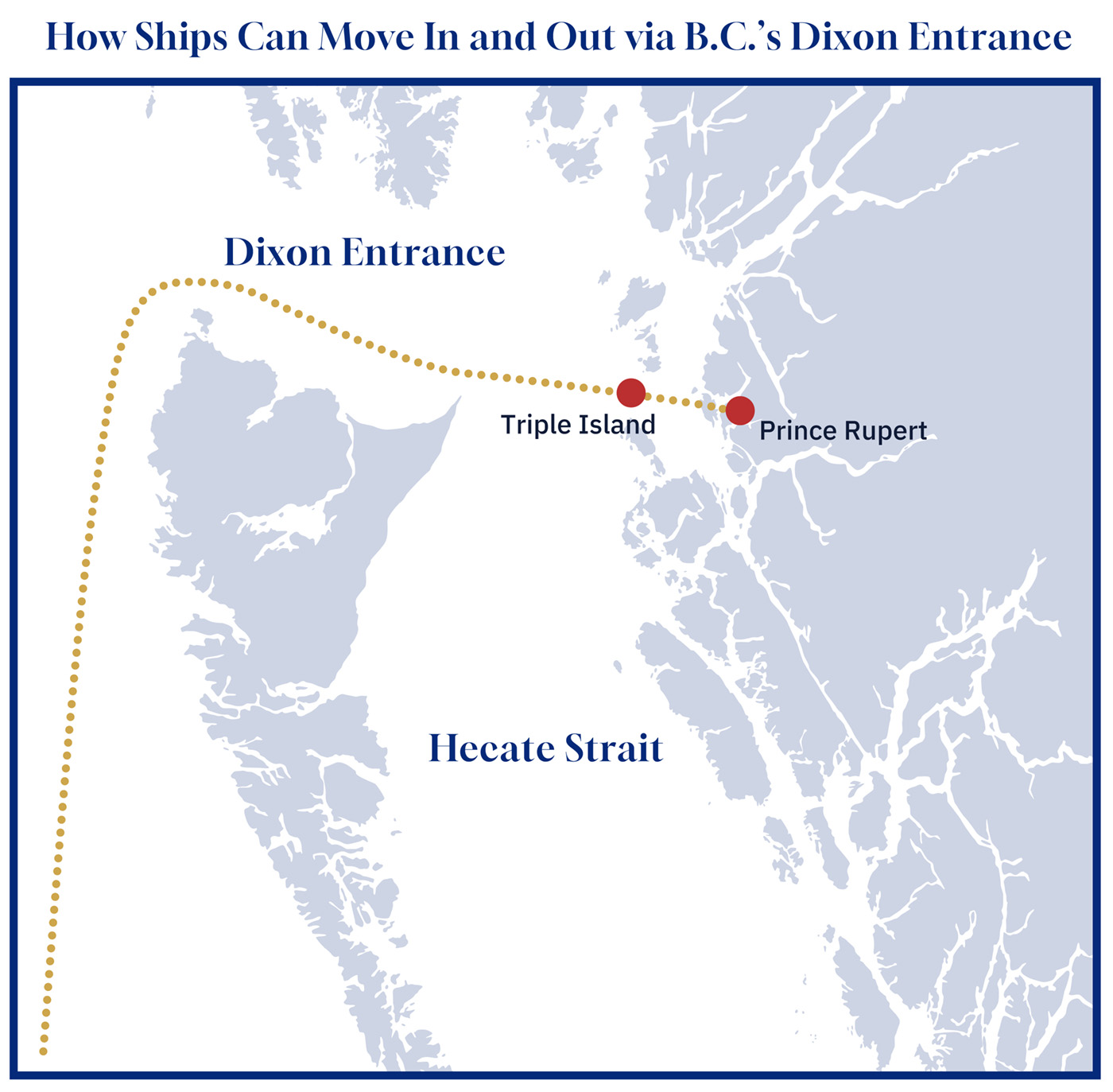

Prince Rupert’s deep-sea traffic does not enter or exit via Hecate Strait exclusively. The port’s commercial marine gateway is Dixon Entrance, a wide and deep outer channel along the Alaska–B.C. boundary.

All deep-sea vessels—bulk carriers, container ships, and LPG (liquified petroleum gas) tankers (which carry propane, by the way)—pick up their B.C. Coast marine pilots at Triple Island, which sits directly on this route. The addition of a pilot adds local expertise in seamanship to the crew and is required by law for large ships.

According to Canada’s general pilotage regulations, Triple Island is the mandatory pilot boarding station for the port. In other words, the entire navigation system assumes ships will use Dixon Entrance.

But that’s not to say nobody sails through the strait just south of it.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

In addition to a year-round passenger ferry, certain container ships operate on fixed, multi-port rotations, more like bus routes than point-to-point trips. A typical West Coast rotation might include Prince Rupert, Vancouver, Seattle, and sometimes Oakland or Long Beach.

When a carrier has multiple stops along the coast, the most efficient southbound path naturally threads through Hecate Strait toward Vancouver.

A crude tanker, whose job is to move a single cargo from its loading terminal to a destination overseas in Asia or the Gulf of Mexico, has no reason to take this detour.

If the intended destination were California or Washington, then yes, a tanker may want to take the southern route. But to imply tankers must travel through the strait is not true.

Furthermore, a tanker moratorium carve-out could theoretically open up only Dixon Entrance, while maintaining the ban on Hecate Strait.

Claim 2: Alaska tankers already go through the same waters. So why can’t Canada?

Scheer’s argument—which kicked off this spat—contains its own misleading premise.

“Why are the Liberals keeping in a law that prevents Canada from exporting our oil while U.S. tankers travel through the exact same place?” the Conservative MP asked in the featured snippet in May’s video.

But Scheer’s claim is only true if you zoom out far enough.

Alaska’s crude tankers from Valdez do not run through Dixon Entrance or Hecate Strait. They sail far offshore down the Gulf of Alaska, then along the outer edge of Haida Gwaii. On a map, that looks like a short distance, but in practice, a tug dispatched from Prince Rupert would take a good part of a day to reach it.

In short, those tankers from Alaska only come inshore when approaching refineries in Washington state. They are not transiting B.C.’s coastal channels, and they are certainly not using the approaches that a hypothetical Canadian oil export terminal would rely on.

Therefore, Scheer’s claim only works if you ignore the details.

An aerial shot of Fairview Container Terminal, a key hub in Prince Rupert’s port network. Credit: Prince Rupert Port Authority.

Claim 3: The North Coast is one of the most dangerous waterways on the planet

This statement from May shows up frequently in environmental campaigns, but not in hydrographic publications, pilotage manuals, or Transport Canada risk assessments.

Yes, Hecate Strait can present choppy seas in certain wind and tide combinations. But so can the Cabot Strait, the Bay of Fundy, and the Juan de Fuca Strait.

The frequently quoted line about Hecate Strait being “the most dangerous body of water in Canada and fourth most dangerous on the planet” appears to come from an Environment Canada reference made popular by Paddling Magazine detailing a story about a stand-up paddleboard enthusiast who embarked on such a journey.

One industry source who spoke with The Hub, who is familiar with vessel traffic in the region, said they’d never heard the waterway being described in those “most dangerous” terms in all the years of their career.

Another popular claim about the waves reaching 10 to 20 metres to “expose the sea floor” also appears to come from a non-scientific source—John Vaillant’s 2005 literary nonfiction The Golden Spruce.

In its own description of the harbour, the Prince Rupert Port Authority calls it a “deep, ice-free inlet with easy access and can be entered at all times and in all seasons.”

The port authority declined to comment on this story.

If the region were truly as uniquely hazardous as claimed, it’s a wonder BC Ferries manages to run a scheduled passenger service between Prince Rupert and Haida Gwaii year-round.

And if a paddleboarder can make the crossing, commercial ships certainly can (not that a tanker must, as explained earlier).

Claim 4: Oil tankers introduce risks that bulk carriers or LPG tankers do not

This claim ignores both modern tanker design and what is already operating safely in Prince Rupert.

The port already handles LPG carriers, which operate under strict, customized safety and tug escort requirements, often tethered through the narrowest channels. Crude tankers would face similar or stricter rules, shaped by their own risk assessments.

Modern tankers are double-hulled, have redundant power systems, use advanced GPS-aided navigation, and operate under mandatory pilotage.

Globally, the most consistently cited leading causes of major marine accidents for large commercial vessels are collisions and groundings. Both are more common in congested ports like Singapore, Amsterdam, and Los Angeles than in Prince Rupert’s relatively empty approaches.

In fact, in its submission to a Senate committee on the issue of C-48, the Prince Rupert Port Authority emphasized that multiple independent assessments have ranked its approaches among the lowest risk marine corridors on the West Coast—significantly safer than the confined, high-traffic port areas around Vancouver.

Propane moves through Prince Rupert via the Ridley Island Propane Export Terminal. Credit: Prince Rupert Port Authority.

What’s in the tanks matters enormously for the consequences of a spill, to be sure, but to pretend crude is the only hazardous cargo on the coast makes little sense. Beyond propane, LNG is supposedly a big part of Prince Rupert’s export future.

On a smaller scale, commodities like methanol, gasoline, and diesel also move up and down the coast, mostly for domestic use in B.C. and Alaska, often on barges or small cargo vessels.

Claim 5: The tanker ban proves it’s dangerous

As May correctly noted, the original 1972 tanker moratorium was a voluntary arrangement. It emerged from a mix of political and environmental pressures at the time, including growing tensions with the U.S. over the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and the subsequent expected surge of tankers.

What followed was a series of policy choices that eventually pushed loaded tankers far offshore, based on worst-case drift scenarios—when a vessel loses propulsion due to engine failure or otherwise, and how long it would take for rescue tugs to reach it.

View reader comments (15)

Debates about whether that framework still makes sense today are worthwhile, but they should start with an honest accounting of how conditions have changed in the years since.

It’s worth remembering that the tanker ban 1.0 dates back more than half a century, long before the development of today’s safety practices, the invention of GPS navigation, AIS tracking, real-time weather modelling, and even cellular and satellite phones.

If May wanted to prove her point, she should’ve sent it by telegram rather than a video on the internet.

Honest debate and policies needed

None of this means marine transport is risk-free, even in 2025.

But any discussion about a carve-out of the tanker ban should be grounded in good-faith arguments. It’s in everyone’s interest to prevent a spill. Scare tactics and a scribbly line down a whiteboard just won’t do.

If May really wanted to pour some cold water on the idea of exporting oil via B.C.’s North Coast, she could’ve easily made an economic case against it.

The higher costs of mandatory tug escorts, the constraints of running smaller tankers, the real operational challenges posed by the geography, the limited time and tide windows, and the need to formally integrate Indigenous marine guardians and coastal pilots into any future traffic regime are all real hurdles.

Perhaps they’re just not the ones that appeal to environmentalists.

Do oil tankers have to navigate the Hecate Straight if Canada wants to export crude from Prince Rupert?

Are claims about the Hecate Strait as “the most dangerous waterway in Canada and fourth most dangerous in the world" grounded in marine safety assessments?

Andrew Scheer argues that U.S. oil tankers already sail “through the exact same place,” so Canada should too. Does he have a point?

Comments (15)

Great analyses!