Now that Rex Murphy’s gone, Canadian originals are thin on the ground. We used to specialise in the type. Hugh MacLennan; Mordecai Richler; Ian Tyson: men of very different backgrounds who, for all their occasional international acclaim, could not be mistaken for anything but Canadian. There aren’t many left and likely there won’t be any more: the internationalisation of mass culture militates against it. Generations raised on globalised cultural slop will struggle to root themselves in a specific place and past.

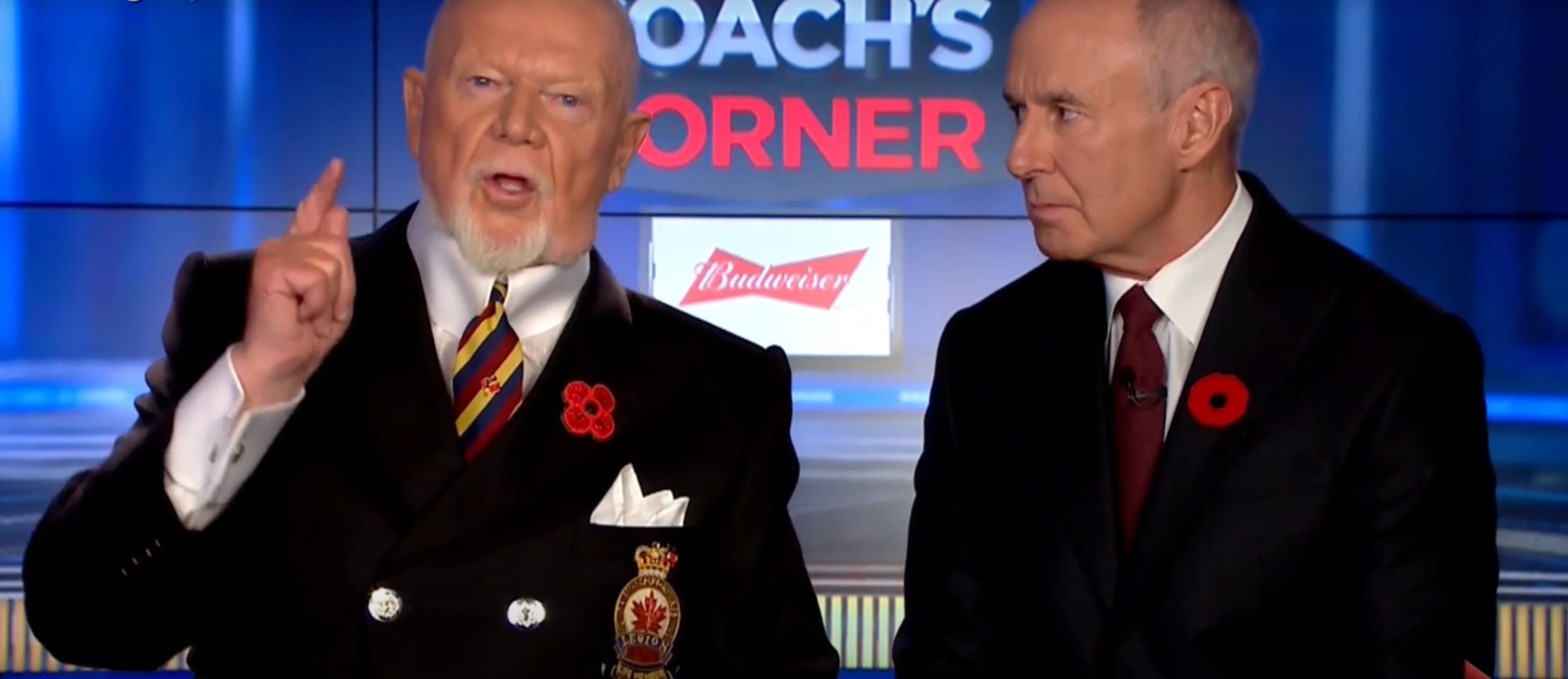

What qualifies Don Cherry as the last Canadian original?

For one, he grew up in a Canada that was distinctly Canadian in a way it is hard for anyone born since the advent of cable television to appreciate. The Canada of Cherry’s childhood was a loyal Dominion whose young men were overseas fighting for King and Country while he was memorising maps of the Empire at Kingston’s Rideau Elementary. Culturally, the Canada of the 1940s was only a half-degree removed from the Old Country, but that half-degree mattered. It marked us as something different—not-quite British but assuredly not American either. Cherry’s grandfather, Jack, a North-West Mounted Policeman who busted American bootleggers on the prairies, embodied the national character.

By the time Cherry came of age in the 1950s, Canada was evolving from an outpost of Empire into an independent country, legally and culturally. Already, for more than half a century, we had been assimilating the children of immigrants and making loyal Canadians of them. Nowhere was this new Canada more evident than on the rinks of the country’s amateur and professional hockey leagues. Look at the roster of Cherry’s Barrie Flyers in 1953, and amidst the Smiths, Whites, McNeils, MacQueens, Robertsons, and Cherrys, you’ll find a Poliziani, a Ranieri, a Stankiewicz, and a Hiironen.

This wave of non-British Europeans shaped Canada, but more importantly, the children of these newcomers were shaped by the Canada they joined—a country whose institutions, education system, and social habits were still overwhelmingly British and assured enough in their imperial identity to accommodate newcomers just enough to assimilate them. Canada offered its new citizens the same deal it offered its working-class native sons like Cherry: work hard, earn your way, love your country—and fight for her if necessary—and you will have a place here.

Is Don Cherry's 'Canadian original' status tied to a specific historical era?

How does the article define 'Canadian original' in contrast to modern identity?

What role did immigration play in shaping the Canada of Cherry's era?

Comments (26)

Don was a classic. He deserves the Order of Canada and a proper apology from the CBC.