Prime Minister Mark Carney’s keynote address at the World Economic Forum in Davos was one for the ages. Facing a global audience rattled by trade wars and geopolitical fragmentation, the prime minister offered a bold vision of Canada as a “safe harbour,” a stable, reliable partner in a chaotic world.

It was exactly the message the world needed to hear, and Canada needs to send. The country is right to rally behind this ambition. When the prime minister speaks of fast-tracking a $1 trillion investment target, he correctly identifies the scale of the challenge. He understands that for Canada to maintain and improve its standard of living, we must build.

But ambition must eventually meet reality. Parliament returns with a new session, and Carney, back on home soil, will have to turn his lofty words into tangible solutions. While the prime minister’s focus is right, the economic reality on the ground is stark. We are starting this trillion-dollar race from a deep deficit. To turn the Davos pitch into domestic prosperity, the challenge isn’t just attracting new money but stemming the structural tide of capital that has been leaving our shores for a decade. As the graphs below show, Canada faces an investment crisis and capital flight problem.

Trillion-dollar exodus

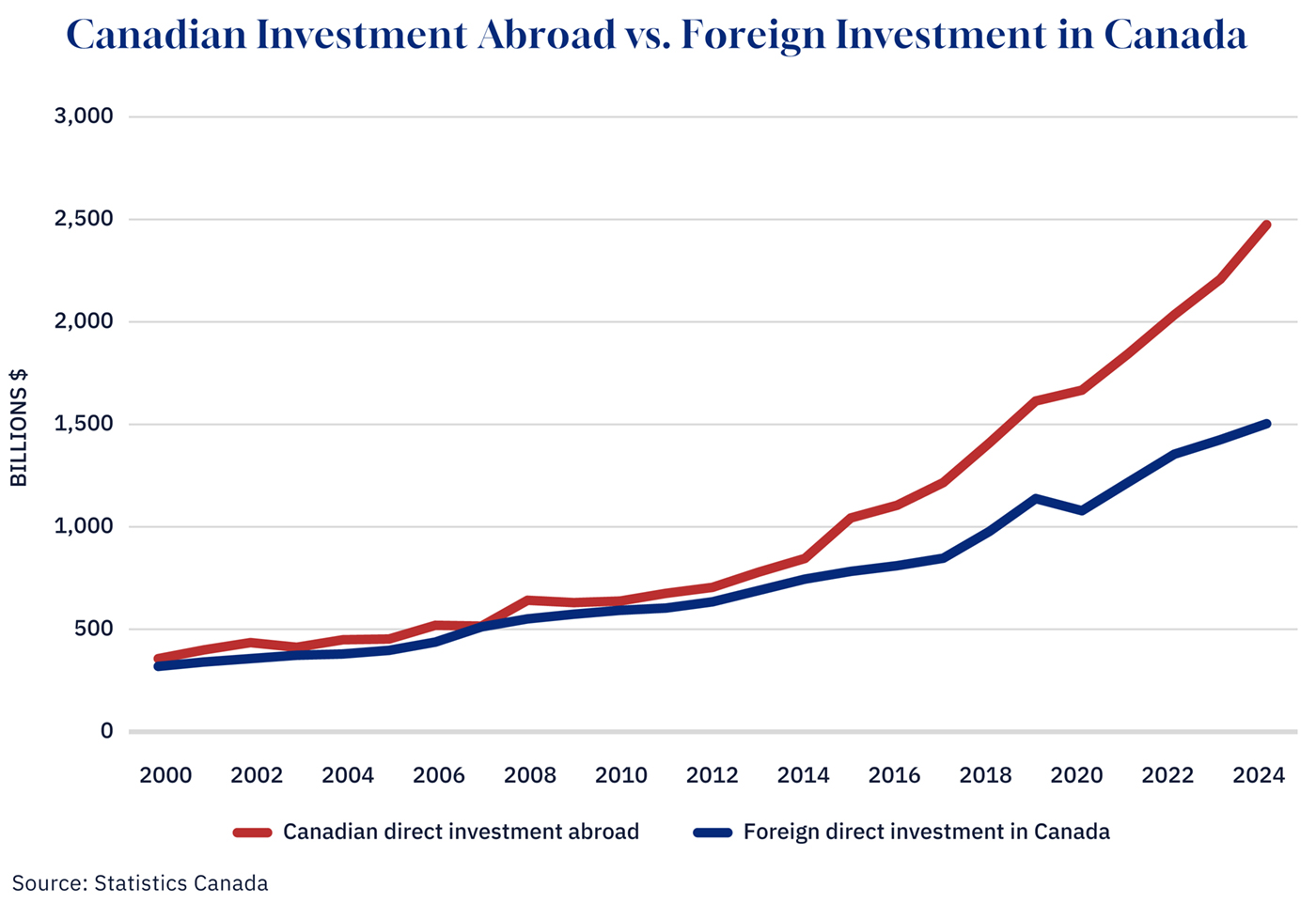

Canada’s stock of foreign direct investment tells a sobering story. This accumulated scorecard shows where capital has settled over decades, including the total value of factories, mines, and corporate divisions that foreign companies own in Canada versus what Canadian companies own abroad.

If Canada were a magnet for global capital, foreign assets here would rival or exceed our investments abroad. Instead, the numbers reveal a structural exodus. While foreign investment in Canada grew from approximately $320 billion in 2000 to $1.3 trillion in 2024, Canadian direct investment abroad surged from roughly $360 billion to $2.3 trillion.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

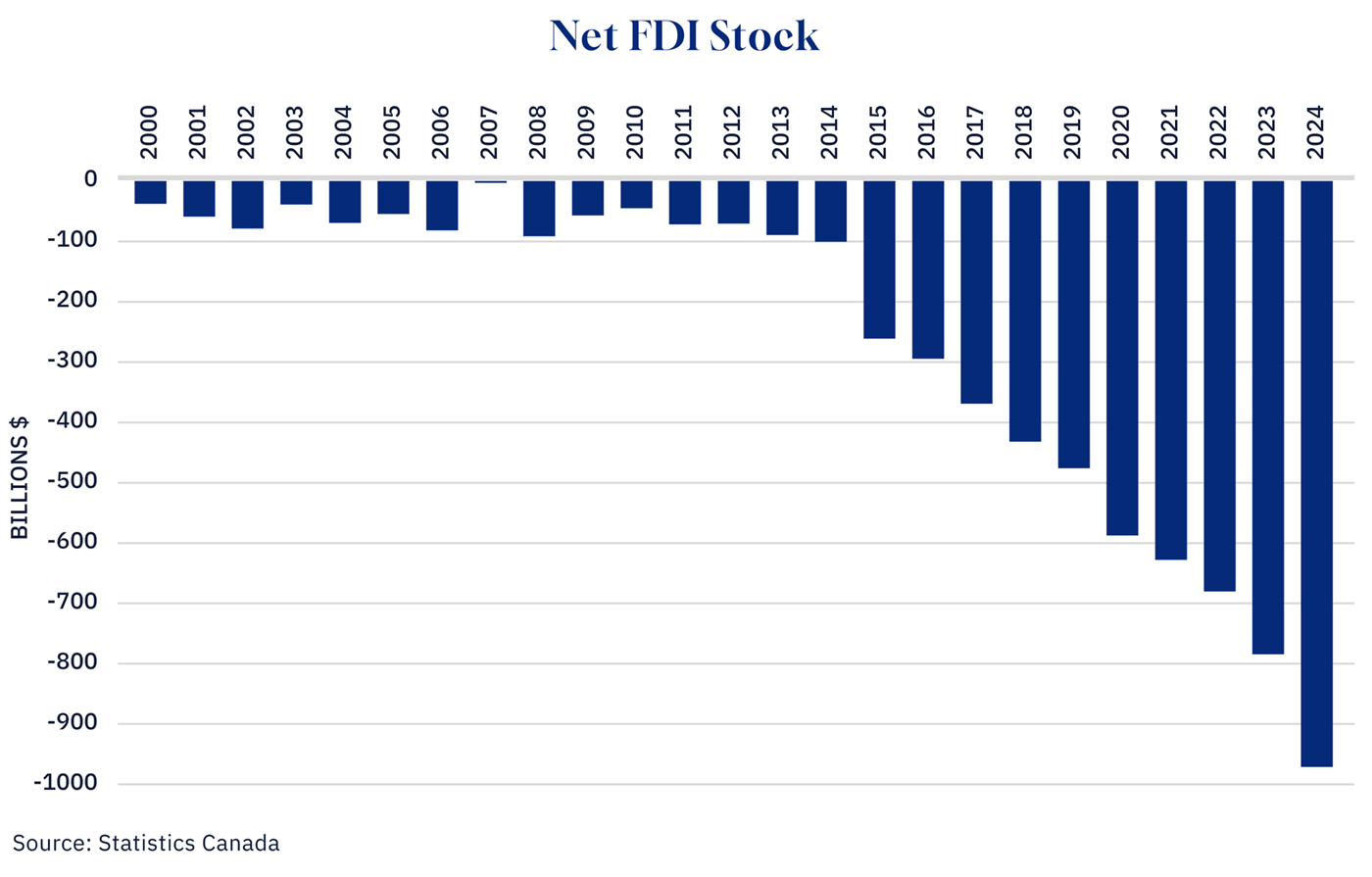

The gap has widened dramatically since 2014. We have become a massive net exporter of capital. As of 2024, our net FDI stock position stands at roughly negative $1 trillion—ironically, the government’s target for new investment.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

In simple terms, Canadian individuals, companies, and pension funds have invested a trillion dollars more abroad than the world has invested here. When our own Maple 8 pension funds and corporate champions deploy capital in the United States and other countries outside Canada, they are voting on Canada’s competitiveness.

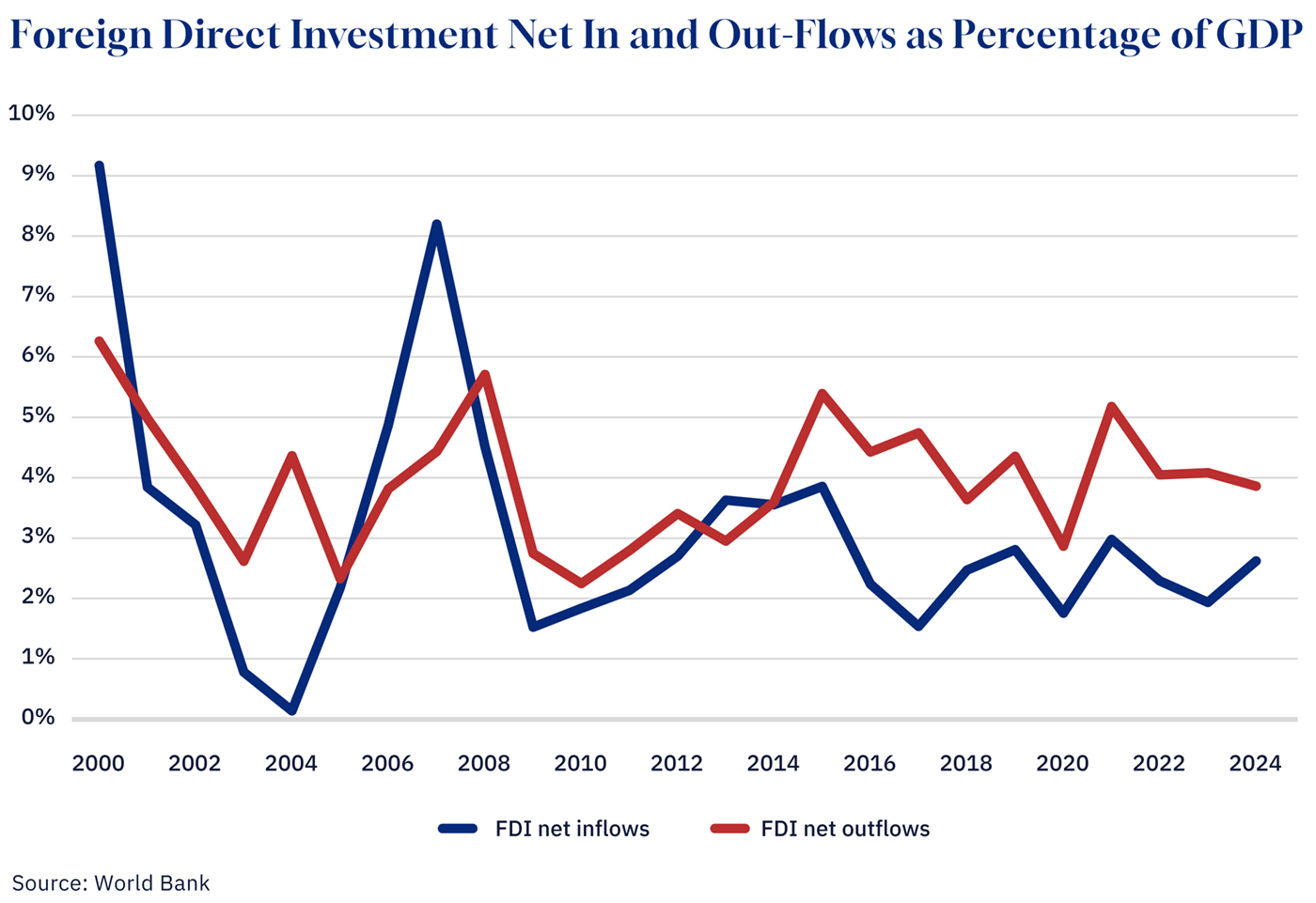

Since 2014, net FDI outflows have consistently outpaced inflows. In 2024, outflows hovered near 4 percent of GDP, while inflows barely exceeded 2.5 percent. The prime minister’s sales pitch is essential, but it fights a current that has been flowing against us for 10 years.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Eroding capital stock

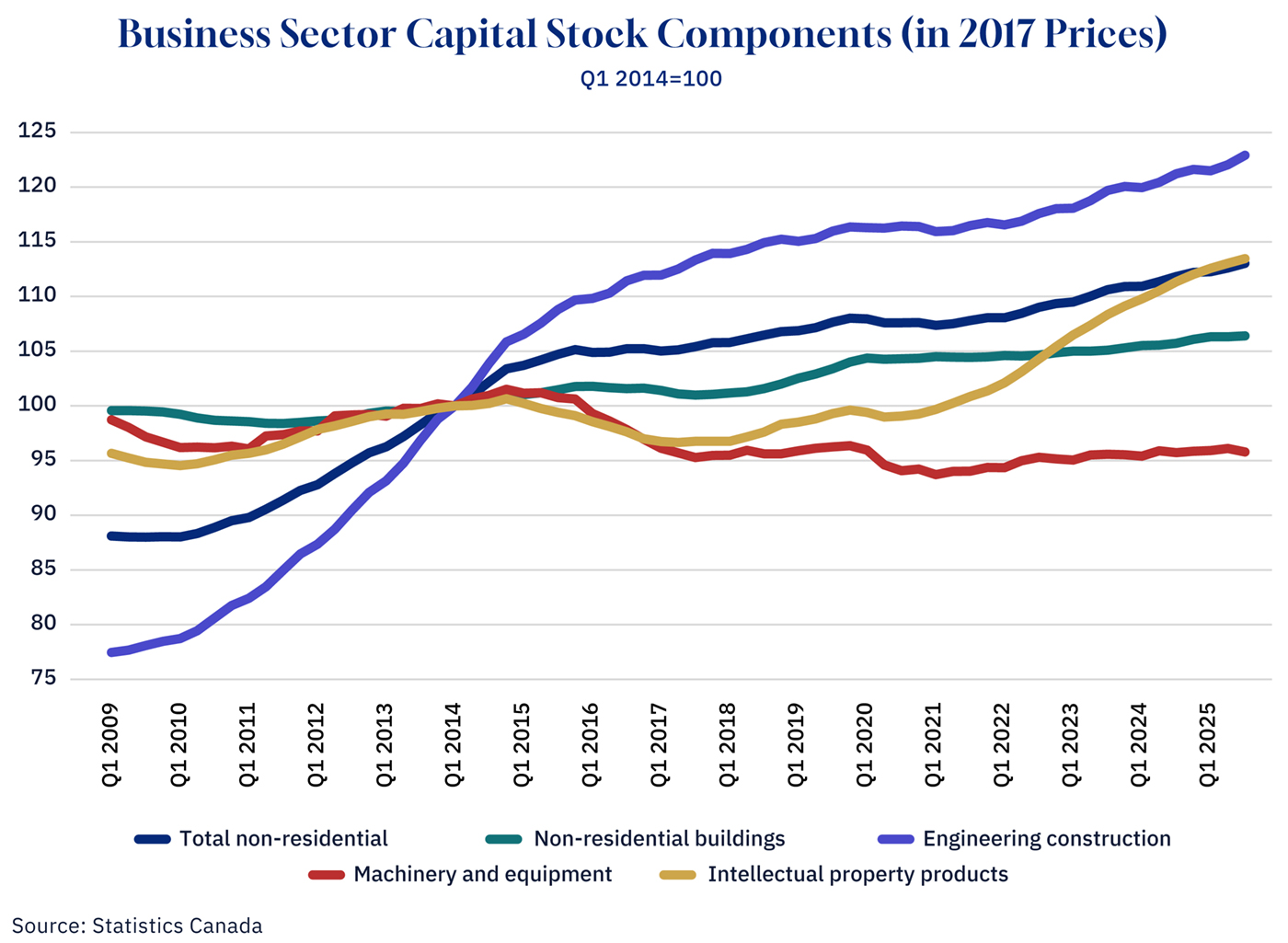

If the flow of foreign money is slowing, the accumulated stock of domestic tools and technology is actually shrinking where it counts most.

The business sector capital stock reveals a crisis in our industrial capacity. Between Q1 2014 and Q1 2024, total non-residential capital stock (measured in constant 2017 prices) grew by just 10.9 percent over the entire decade.

But the details are damning. While engineering construction grew by 20 percent, the stock of machinery and equipment (the actual physical tools, robots, and assembly lines that drive productivity) declined by 4.6 percent, dropping from roughly $370 billion to $353 billion.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Canadian businesses today operate with less machinery and equipment than they did 10 years ago. Meanwhile, our stock of intellectual property products (software, R&D, databases) grew by just 9.8 percent over the entire decade, an anemic pace for a country competing in the knowledge and intangibles economy.

We are not just failing to modernize. In some sectors, we are de-capitalizing.

Shrinking toolkit

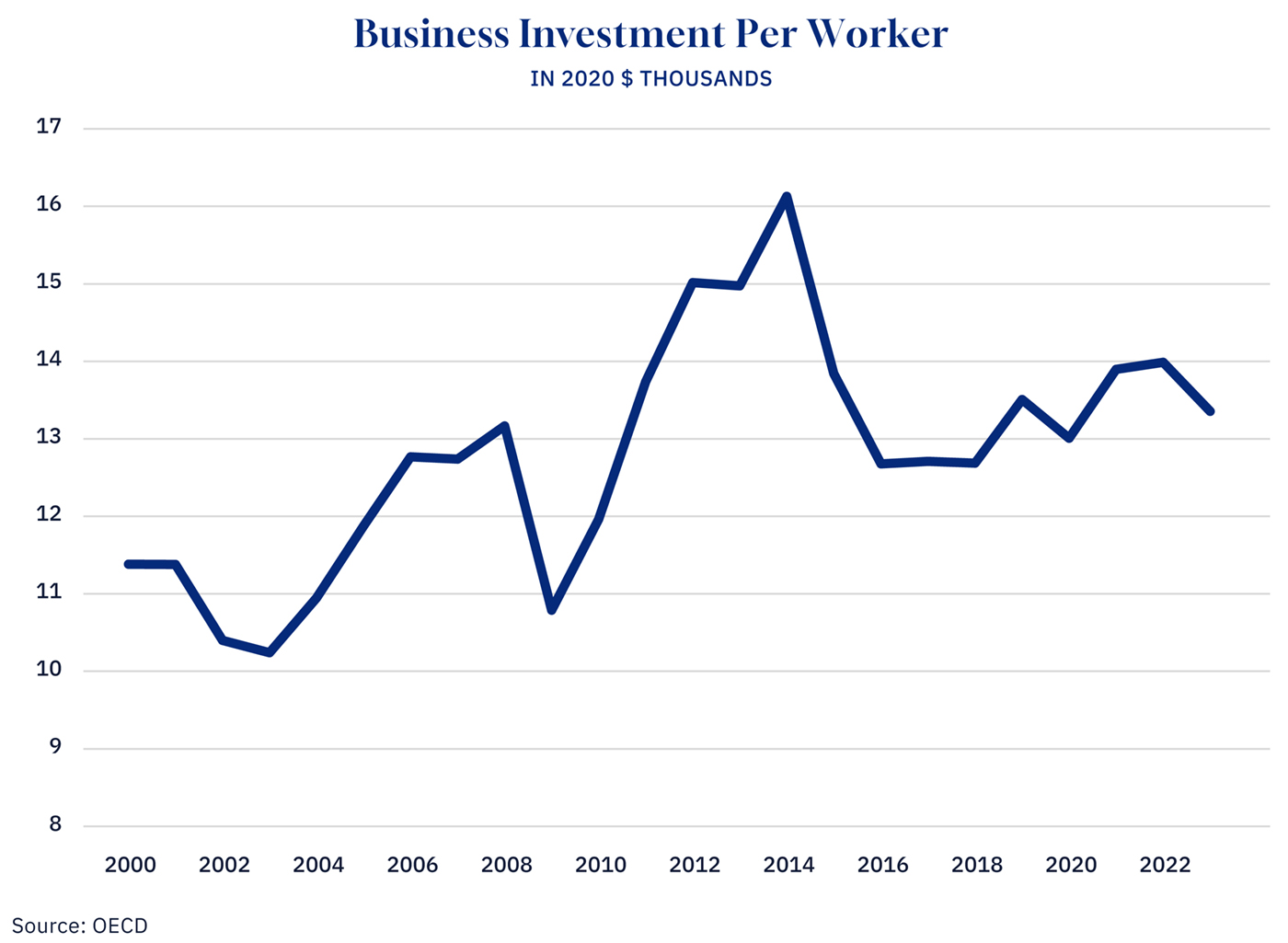

Perhaps the most troubling metric is the one that impacts workers’ paycheques: business investment per worker.

The reliable path to higher wages is higher productivity. But in Canada, we are asking our workforce to do more with less. Since peaking in 2014 at approximately $16,100 per worker (in 2020 dollars), business investment per worker has been on a persistent downward slide, falling to roughly $13,400 by 2023.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

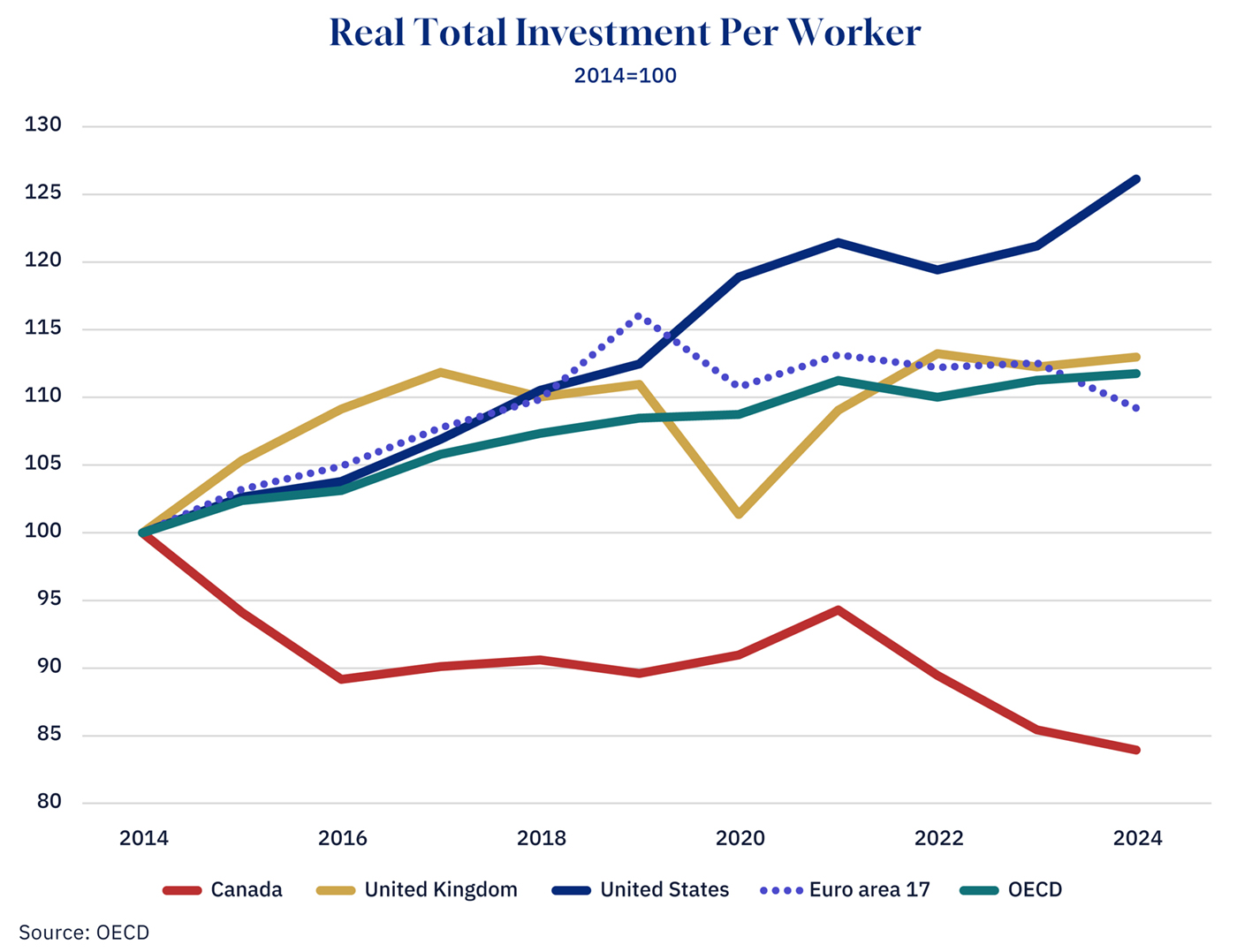

The gap becomes starker when examining total investment per worker across countries. As Canada’s real total investment per worker has collapsed by 16 percent since 2014, over the same period, the United States has seen investment per worker rise by more than 26 percent. The gap between Canadian and American workers is widening, along with workers in the United Kingdom, the Euro area, and the broader OECD.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Global investment laggard

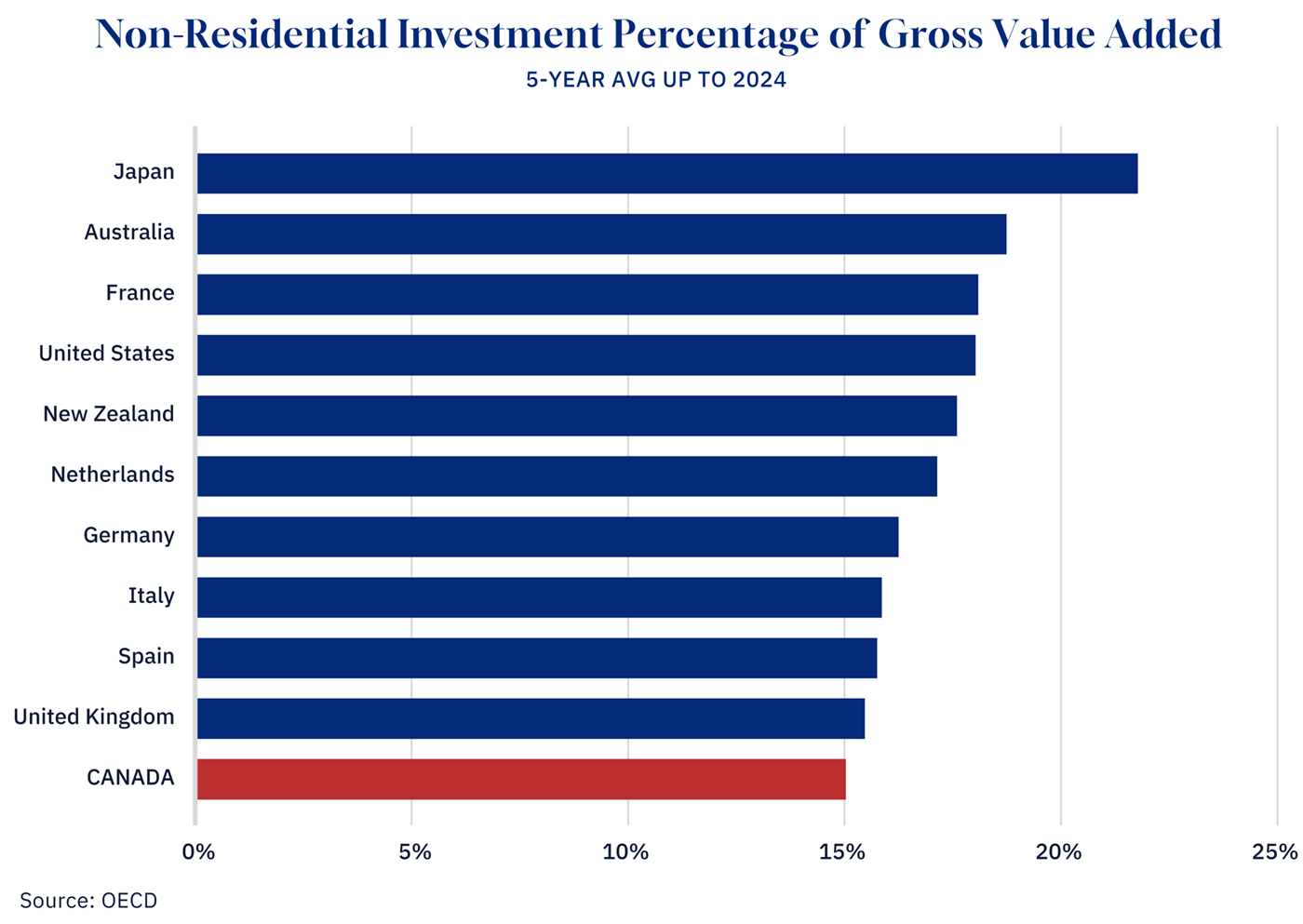

Canada fares no better among G7 and Commonwealth peers. Non-residential investment as a share of gross value-added shows Canada ranks at the bottom among our major competitors.

Based on the five-year average up to 2024, Canada is investing just 15 percent of its gross value added in non-residential assets. Compare that to the United States at 18 percent, Australia at 18.7 percent, and Japan at 21.8 percent. We also trail France, New Zealand, and the Netherlands.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

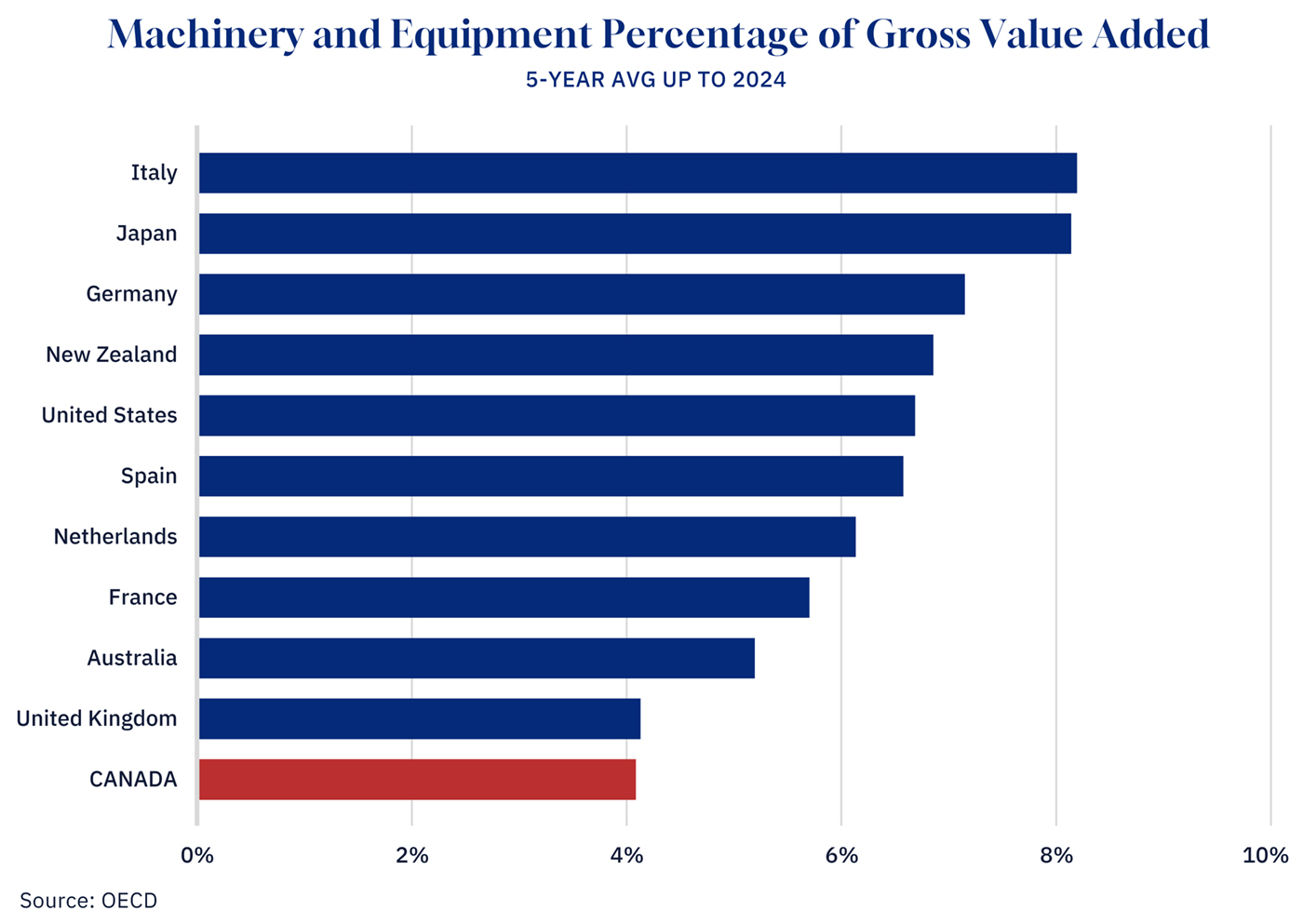

The composition of that investment is equally concerning. Canada invests just 4.1 percent of gross value added in machinery and equipment, placing us at the bottom of our peer group and well below the United States (6.7 percent), and leaders Japan and Italy (both over 8 percent).

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

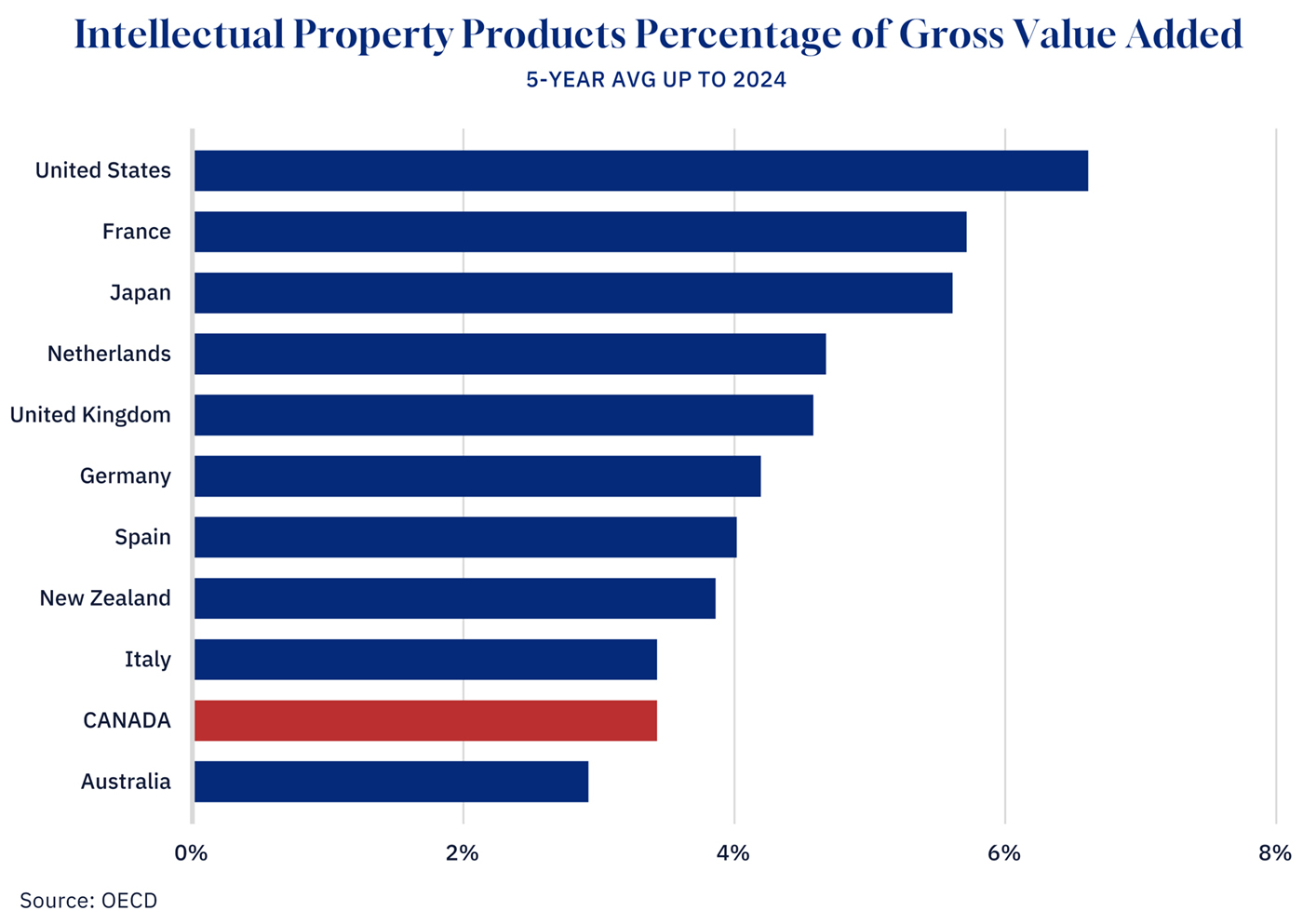

In intellectual property products (the software, patents, and R&D that define competitiveness in the modern economy), Canada invests just 3.4 percent of its gross value added, roughly half the American rate of 6.6 percent. We are trying to compete in an innovation economy while under-investing in the very assets that define it.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Widening innovation gap

If the decline in physical machinery is worrying, the collapse in our capacity to innovate is catastrophic. According to the latest report from the Council of Canadian Academies, Canada continues to suffer from a deepening “innovation paradox”: we have world-class university research, but our businesses fail to commercialize it.

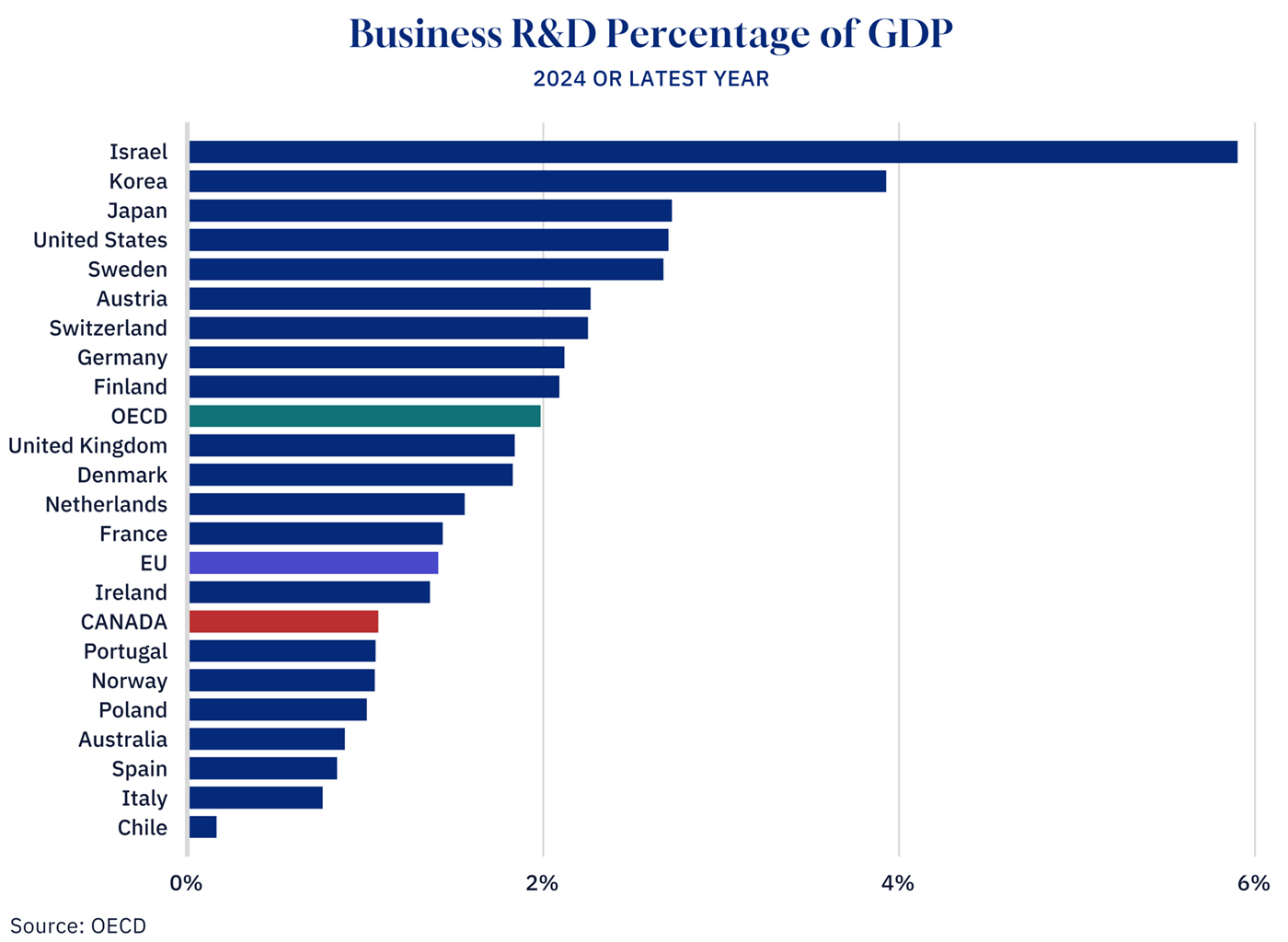

Canada’s business expenditure on research and development (BERD) intensity fell from about 77 percent of the OECD average in 2000 to just 57 percent in 2023. While our global peers race to compete in the knowledge economy, Canadian business R&D spending as a share of GDP sits at just 1.1 percent, well below the OECD average of 2.0 percent.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

To put this in perspective: a single American tech giant like Amazon now spends nearly three times more on R&D than the entire Canadian business sector combined. When Canadian companies do not invest in R&D, they do not own the intellectual property of the future. They merely pay rent on it.

Venture capital paradox

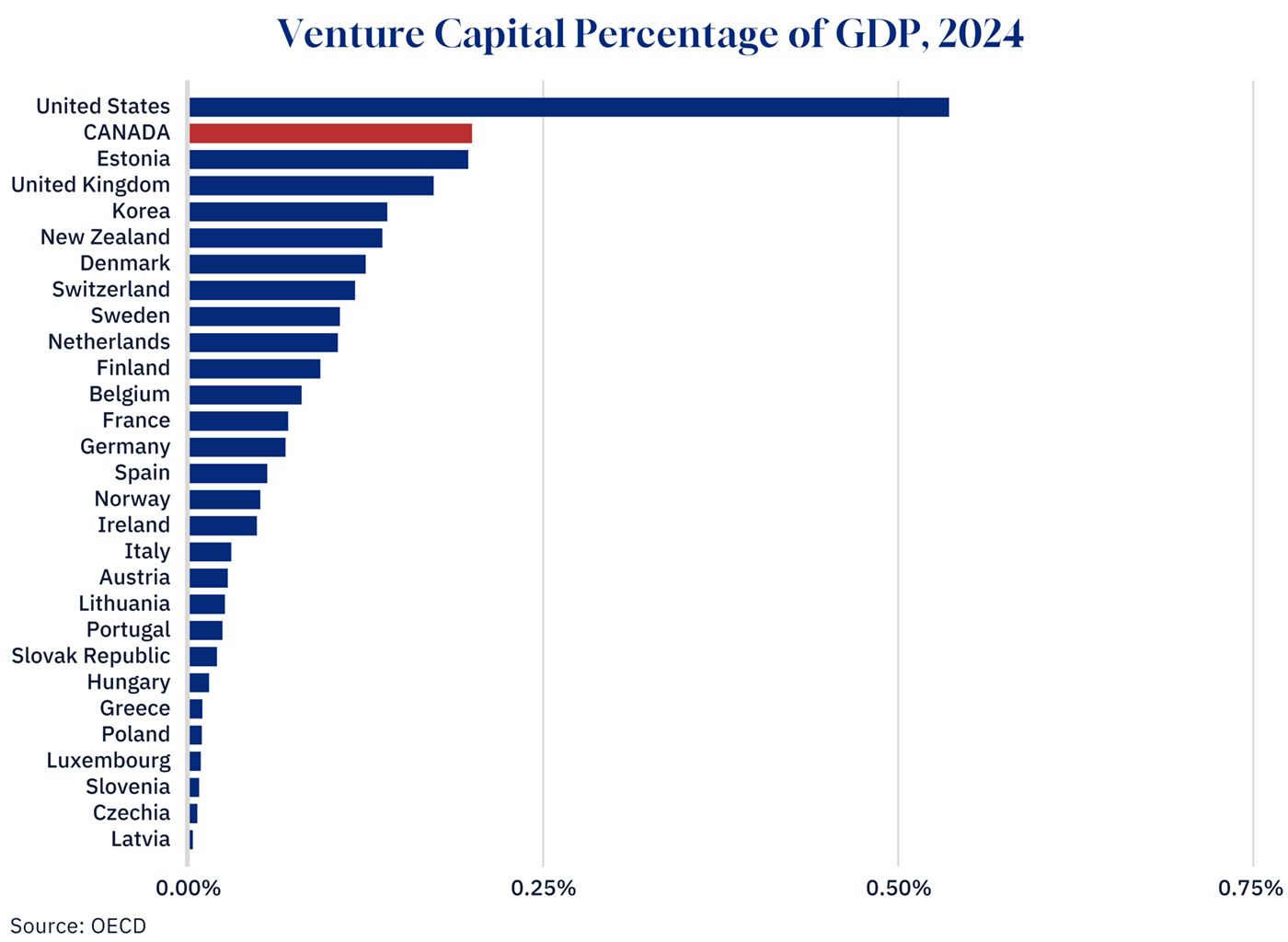

The venture capital landscape presents a more nuanced picture. On the surface, Canada’s venture capital investment as a share of GDP appears relatively strong at 0.2 percent in 2024, tying us for second with Estonia among OECD countries. Only the United States, at 0.86 percent of GDP, significantly outpaces Canada among large developed economies.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

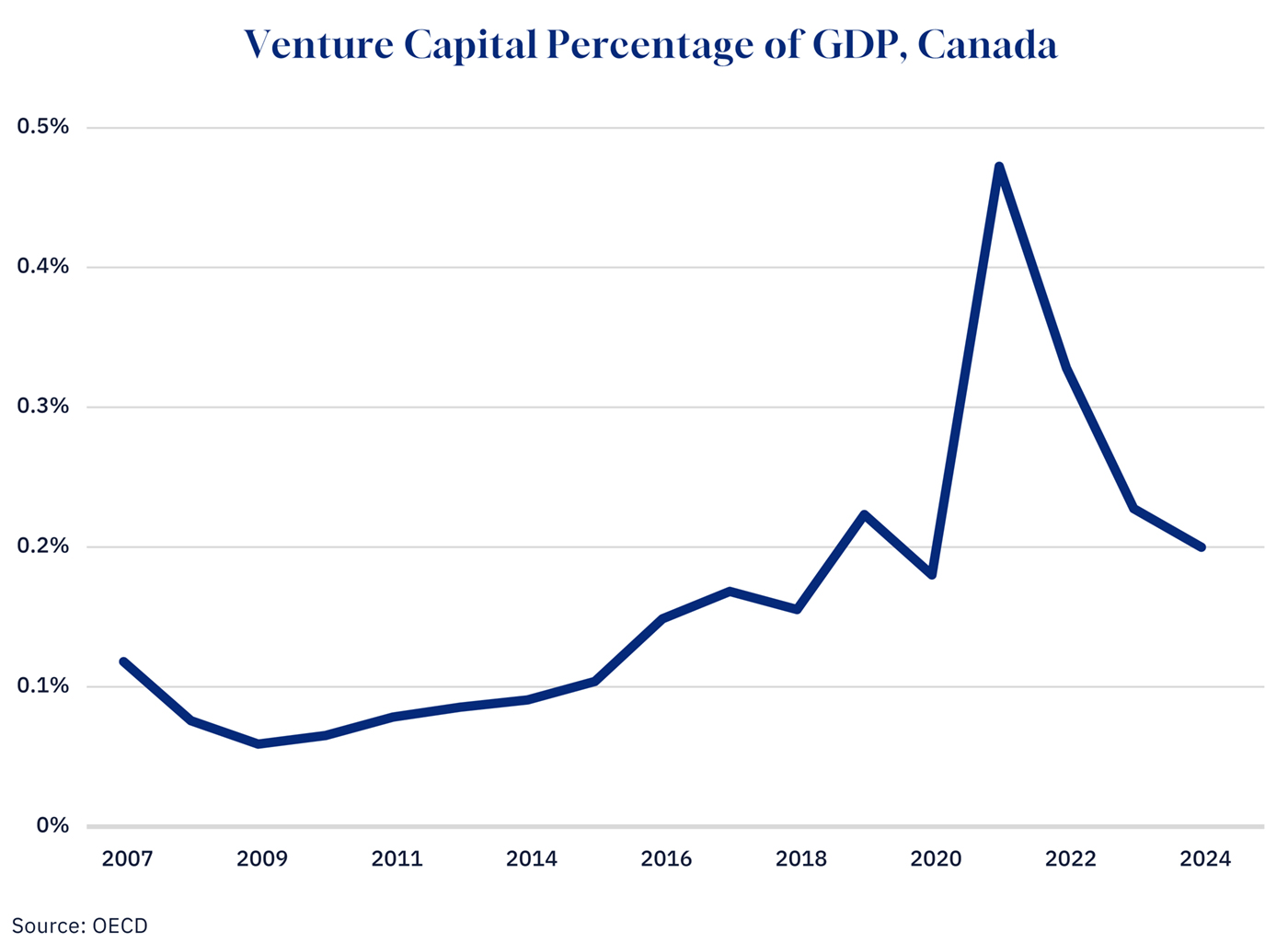

However, the trend over time is less encouraging. After hitting a peak during the pandemic boom, venture capital intensity has been declining. As a share of GDP, the intensity fell by more than half, from nearly 0.5 percent in 2022 to 0.2 percent in 2024.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

This decline matters given the global competition for innovation capital. According to a recent BDC report, Canadian venture capital is increasingly concentrated in later-stage deals while early-stage funding (the oxygen that fuels startup ecosystems) has contracted sharply. We risk creating an environment where Canadian entrepreneurs secure seed funding to prove their concepts, only to be forced south of the border to scale.

Matching policy to the pitch

Prime Minister Carney’s diagnosis at Davos was correct: the world is fracturing, and Canada has a unique opportunity to be a reliable partner and home to investment. His ambition is exactly what the moment demands.

But a sales pitch, no matter how compelling, cannot override the fundamental economics of return on investment. Canada has become a harder place to invest, scale, and justify deploying capital compared to our peers.

Talk alone won’t fill the trillion-dollar hole. It will require bold, structural policy reform to buttress the prime minister’s state-to-state diplomacy. We need to make Canada investable again, not just for foreign capital, but for our own pension plans, entrepreneurs, and growing companies. The “safe harbour” the prime minister described is within reach, but we must build it on a foundation of competitive taxes, streamlined regulation, competition, and a relentless focus on productivity.

Canada faces a significant “capital flight crisis,” with a trillion-dollar gap between Canadian investment abroad and foreign investment in Canada. Despite Prime Minister Mark Carney’s “safe harbour” pitch, Canada is coming off a decade-long trend of net capital outflows. This is exacerbated by declining business investment per worker, a shrinking stock of machinery and equipment, and underinvestment in R&D, leading to lower productivity and wages. Canada lags behind global peers in key investment metrics, particularly in machinery, equipment, and intellectual property. To achieve its investment targets, Canada needs structural policy reforms to become more investable.

Canada's 'safe harbour' pitch: Can words alone fix a $1 trillion capital flight crisis?

Why are Canadian businesses investing less in machinery and equipment?

How does Canada's declining business R&D spending impact its global competitiveness?

Comments (35)

Canada is, has & always will be a resource rich country, that is one of our main strengths

Unfortunately, due to over a decade of Liberal feel good policies, “Net Zero” rhetoric & just plain mismanagement, those strengths have been terribly under utilized.

Horrible Bills like C-69 & C-48 & Canada’s massive red tape bureaucracy have scared away investment who left for more hospitable & profitable pastures.

The Canadian Government seriously needs to get the H*LL out of the way & prove to potential investors that they can be profitable in Canada without waiting the decades necessary for various permits & approvals