Welcome to The Hub’s Federal Election 2021 Policy Pulse, where we’ll be tracking all the policy announcements from the major parties, with instant analysis from our crew of experts.

With the election scheduled for Sept. 20, we’ll be monitoring 36 days worth of policy ideas, so watch out each morning for the day’s live blog where we’ll be tracking every announcement as it happens.

3:30 p.m. — Mail-in ballots aren’t as popular as predicted, but could still make for a long night on election day

By L. Graeme Smith, The Hub’s content editor

The most recent presidential election in the United States was mired by confusion and uncertainty as the final result was not fully known until days after. Election day was November 3, 2020 and most news and media organizations did not call an official winner until November 7, 2020.

This was in large part due to the surge of mail-in votes that took much longer to count and verify, the perhaps predictable outcome of trying to hold an election during a pandemic when remote voting is a more attractive option than in the past.

Canadian elections are not typically marked by such contention or chaos. But Canadians may be forced to exercise some patience as well in this federal election, as a similar delay in counting mail-in ballots may postpone the final call beyond the night of September 20th.

Voting by mail is not new in Canada. Canadians have had that ability for nearly thirty years, since 1993. It is the number of mail-in ballots being returned this year that could cause the lag.

Chief electoral officer Stephane Perrault warned of the possibility during a press conference in August: “I know that Canadians are used to getting complete results on election night but it will be different for this election.”

Advance poll votes are counted prior to election day, but mail-in vote counting does not commence until after polls close and in-person votes are counted.

“The count of mail-in ballots will start after election day. In most locations, this should be done within two days, but in some districts it could take as long as five days,” said Perrault.

This is because poll workers must perform integrity checks to verify that citizens have not voted both by mail and in-person.

Initially, Elections Canada was projecting as many as five million special ballots to be issued and returned this election, including voting kits issued to electors living outside of Canada. By mid-August they revised that estimate down to two or three million, with most to be returned by mail. By comparison, the 2019 federal election saw around 50,000 Canadians vote by mail.

At present, 985,896 special ballot voting kits have been issued by Elections Canada, with 833,597 of those issued to electors living in Canada voting by mail or at an Elections Canada office from inside their riding, 99,994 issued to electors living in Canada voting by mail or at an Elections Canada office from outside their riding, and 52,305 issued to electors living outside of Canada.

The deadline to register for mail-in voting is September 14th at 6 p.m. local time.

2:00 p.m. — Conservatives unveil plan to let new parents earn money while receiving parental benefits

Conservative leader Erin O’Toole was in Ottawa today proposing a plan to allow parents to make up to $1,000 per month in employment income without it affect their parental benefits.

O’Toole said the plan would allow for remote or part-time work while parents are on maternity or paternity leave.

The Conservatives have also pledged to allow families to receive the Canada Child Benefit starting at the seventh month of pregnancy.

1:00 p.m. — The NDP wants to lower the voting age. Here’s what happened in other countries that did the same thing

By Ian Thomson, a public policy researcher

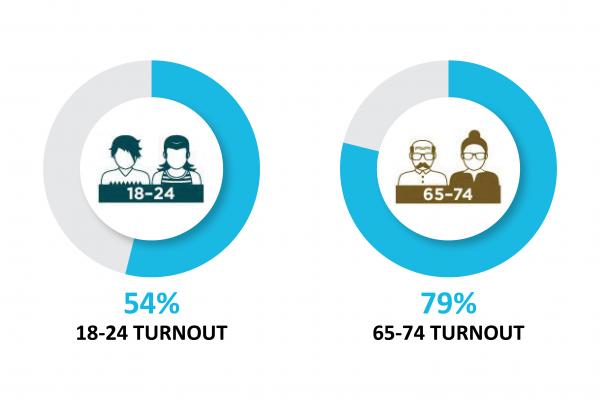

Buried in the back pages of the NDP platform is a proposal to lower the voting age from 18 to 16 years old.

Youth voting is an issue that has barely been mentioned during this year’s election campaign, except in relation to an Elections Canada decision to scrap its Vote on Campus program due to the pandemic and the prospect of a snap election.

Some critics of the program’s cancellation argued the best way to raise historically low levels of youth turnout is to engage people when they are young. The NDP platform makes a similar case.

And even some conservatives have argued that the voting age should be even lower — in fact, all the way down to zero. The demographer Lyman Stone imagines a world where parents make the decision for their children until the kids are old enough — likely in their pre-teens — to do it themselves, increasing civic literacy and leading to a more forward-looking government.

The platform highlights how young people are both increasingly engaged in the world and worried about the effects of climate change and rising inequality. Young people “often see themselves paying the biggest price for the decisions government are making today,” and if they are old enough to work and pay taxes, they should also be old enough to have a say in who forms government.

Arguments both for and against the idea often reference the responsibilities of being a voter in relation to other markers of adulthood, such as being legally and financially independent and/or being married. Furthermore, Canadians in recent years haven’t been particularly supportive of the policy: a 2016 Angus Reid poll found that 75 percent of Canadians oppose lowering the voting age. Interestingly even among younger Canadians (18 to 35 years old), 66 percent opposed lowering the voting age.

However, in the last few years, more jurisdictions have lowered their voting age to either 16 or 17. If such a policy was established, Canada would be following the steps of such jurisdictions as Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador, Austria, Scotland, Wales, Estonia, and several German states. In these jurisdictions, 16- and/or 17-year-olds can vote in some or all elections.

This table, taken from Jan Eichhorn and Johannes Bergh’s 2021 paper, details the countries where the voting age is below 18 across the entire country.

| Country | Minimum Voting Age (years) | Type of election |

| Argentina | 16 | All |

| Austria | 16 | All |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 16 (if employed and paying taxes) | All |

| Brazil | 16 | All |

| Cuba | 16 | All |

| East Timor | 17 | All |

| Ecuador | 16 | All |

| Estonia | 16 | Local |

| Greece | 17 | All |

| Indonesia | 17 (Anyone below 17 years can vote if they are married) | All |

| Israel | 17 | Local |

| Malta | 16 | All |

| Nicaragua | 16 | All |

Eichhorn and Bergh could not find negative effects for lowering the voting age on young people’s engagement or civic attitudes. In many instances, “[e]nfranchised 16- and 17-year-olds were often interested in politics, more likely to vote and demonstrated other pro-civic attitudes (such as institutional trust).” This finding bodes well for the policy, particularly in increasing voter turnout and establishing greater faith in democratic institutions.

Eichhorn and Bergh’s research also examined young people’s voting attitudes and political behaviour. When the voting age is lowered, voter volatility increases as young voters are more often to switch their vote than older voters. For instance, 16- and 17- year old’s voting in the 2014 Scottish referendum were initially less supportive of Scottish independence. Yet by the time of the referendum, this voting group had changed their views embracing independence at a greater rate than Scots overall. Additionally, while young people tend to support centre-left parties, Eichhorn and Bergh note that this is by no means always the case, given youth support for centre-right parties observed in Austria’s 2019 last election. Lastly, lowering the voting age also shifted public views. In places where the voting age was lowered for specific elections, support grew for the voting age to be lowered for all elections.

11:00 a.m. — The only thing clear in this noisy, messy campaign is our lack of unity

By Ray Pennings, the executive vice-president of Cardus

Back in May, I outlined a Liberal playbook which I suggested provided a blueprint for progressives to win elections in Canada. Recognizing that Canadian values are more progressive than conservative, it seemed a prudent projection of where Canada might be heading.

I was riffing from a four-country research project which suggested that progressives succeed when they combine authentic leadership, a sense of insurgency, an ability to unify, and superior organizational innovation. For better or worse, it is clear that the Liberal strategists have not adopted this strategy.

It is the (lack of) a sense of insurgency and a clear articulation of purpose which has left the Liberals most vulnerable. For months in advance of the election, political insiders, including the highly regarded trio of David Herle, Scott Reid, and Jenni Byrne, argued that if the Liberals took advantage of the polls and called an election with an ambitious platform to change the subject from why the election was being called, they would be in the driver’s seat and maintain their strong pre-election polling. For whatever reason, they haven’t done so.

It’s not that the Liberal pitch launching this campaign — “the most significant since 1945” — was entirely disingenuous. The role of government during COVID has grown exponentially. Getting voter input on what should be the new normal could have made for a compelling issue. Instead, the opening day slogans have been followed up with a platform that could just as easily have been a throne speech and legislation, which the NDP almost certainly would have supported.

Superior on-the-ground organization is a core component of a winning strategy. The extent to which the Liberal Party is ahead of its competition (or not) is impossible to assess until after the election. The only thing we can be sure of is that the Green Party has squandered whatever organizational strength it had in 2019 when it fielded an almost full slate of candidates who collectively garnered 6.5 percent of the vote. In this campaign, voters in almost 100 ridings won’t have a Green candidate. This may end up being a significant factor in many local races, depending on how those who voted Green in 2019 decide either to stay home or to cast a ballot for another party’s candidate in 2021. It will be worth watching what happens in closely contested ridings with no Green Party candidate this time around.

Finally, unity hasn’t featured highly at any point in this campaign. Noisy protests have especially disrupted the Liberal campaign, possibly distracting Trudeau and keeping him from getting his message out. Alternatively, they could be a useful foil for him to campaign against. Regardless, it is clear that there is anger is boiling over among some portion of the electorate. The rise in People’s Party popularity is an expression of disunity and frustration, not ambition or hope.

The formula I prescribed back in May may or may not prove accurate. Based on a study of modern progressive movements in western democracies, it still seems to be the most likely way for Liberals to achieve their progressive ambitions. They didn’t follow the pattern, though. Based on polling with 10 days left in the campaign, it appears that a Liberal majority government, almost a foregone conclusion in the spring, is an unlikely outcome.

9:00 a.m. — Most Canadians think Canada’s standing in the world has gotten worse

By Stuart Thomson, The Hub’s editor-in-chief

Canadians are taking a dismal view of their country’s place in the world with a majority agreeing it has gotten worse and only a tiny percentage saying Canada’s global reputation has gotten better, according to an exclusive new poll conducted for The Hub by Public Square Research and Maru/Blue.

Only six percent of Canadians think Canada’s place in the world is better than before the COVID-19 pandemic, with 33 percent saying it’s the same, 39 percent saying it’s somewhat worse and 22 percent saying it’s much worse.

Canadians are also extremely uncertain about the course of the pandemic and their own future, the poll shows.

Many Canadians still fear the worst is yet to come from the COVID-19 pandemic and even more say they are unsure about whether things will get better or worse, despite at least one dose of vaccine reaching nearly three-quarters of people in the country.

One-third of Canadians agree that the “worst is yet to come” in the pandemic and only 19 percent say the worst of COVID-19 is over. Forty-seven percent of Canadians are not sure.

Answering a separate question, about their specific fears about the pandemic, 31 percent of Canadians said they worry that we will never be safe from COVID-19.

This bleak outlook seems to have affected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s standing with Canadians, as he leads his Liberal Party into the final week of a campaign that opinion polls say is deadlocked.

Only 36 percent of Canadians rate Trudeau’s leadership during the pandemic as a good or very good and nine in 10 say he called the election simply because he thought he could win it right now. Nearly three-quarters agree that it was unsafe to call an election now.

The pessimism, about Canada’s place in the world and about one’s personal circumstances, is worst in Alberta.

Forty-two percent of Albertans think Canada’s place in the world has gotten much worse, compared to nearly half of that for the rest of the country. Canadians aged 18 to 34 are the most optimistic about Canada’s place in the world, with only 15 percent agreeing it has gotten worse compared 22 percent nationally.

On how Canadians feel about their own prospects, six in 10 say they worry about their position in society, with the number rising to 66 percent for people under the age of 35.

Albertans are more likely to be extremely worried than other Canadians about their position or their children’s position in society. In Alberta, 23 percent of people say they worry a lot about the future and 35 percent say they worry somewhat. In terms of the total amount of people either worried a lot or somewhat worried, Alberta is about the same as the other provinces.

Three in 10 Canadians say they are doing somewhat or much worse than two years ago and only two in 10 say they are doing better than two years ago. Fifty-one percent of Canadians say they are about the same.

This research was conducted with an online survey of 1,500 Canadians from Sept. 3 to Sept. 6 who were selected from the Maru Voice panel. Although the data have been weighted to reflect the make-up of the country, no estimates of sampling error can be calculated because the respondents originally self-selected for the panel.

7:00 a.m. — Where the leaders are today

Liberal leader Justin Trudeau will make an announcement at 1:30 p.m. in Vancouver.

Conservative leader Erin O’Toole will be in Ottawa to make an announcement at 11 a.m.

NDP leader Jagmeet Singh will be in Sioux Lookout to make an announcement at 9 a.m.