We tell ourselves a few different stories about the question of progress: the Enlightenment, the Marxist, and the Postmodern prominent among them.

All boats have been steadily rising, unevenly, and in fits and starts over time, but exponentially so after the Enlightenment. This is the view of progress as improvements in quality of life.

To others, progress is a bit of a mirage. Yes, we are healthier, wealthier, and safer, but the core of what it means to be human, and its challenges remains unchanged — we are selfish, cruel and domineering. The strong oppress the weak in a new guise.

You might also think, who’s to say? Isn’t talk of progress really a non-starter? There’s little meaning to life beyond what we make up in our own little heads. Self-actualization and determination are the only games in town.

Though onto something, there are problems with each.

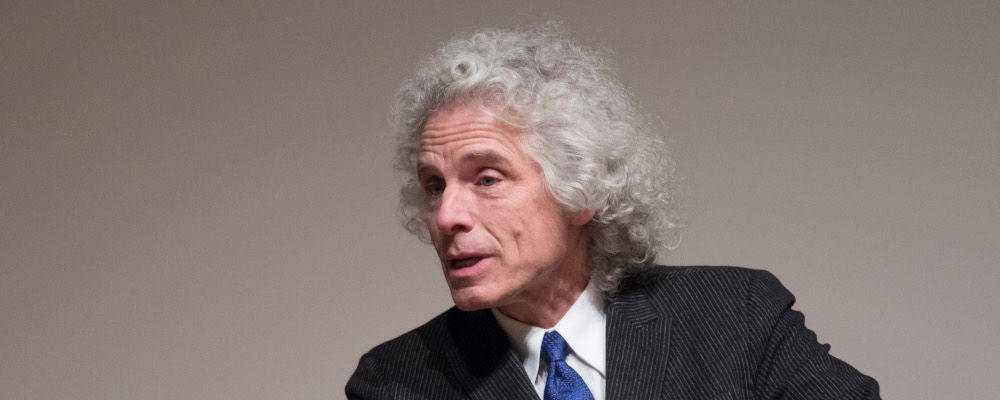

For all the data points and statistical arguments marshalled in Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now, Max Rosen’s Our World in Data, and Marian Tupy’s Human Progress, the problem is one of method. You’ll never find wood with a metal detector, and you just can’t smell a sight.

Through our own experience, we can all come to realize that happiness and fulfilment are much more than improvements in quality-of-life indicators. As we know, after a certain threshold of meeting basic needs and income security, there are diminishing returns. A troubling realization that even yuppies and social climbers inevitably stumble upon is that many people who are considered poor and unsuccessful — by the standards of quality-of-life metrics — are actually happier than themselves, and even significant portions of people in wealthy countries.

The gap in the Enlightenment story is that the good things in life are not found in the amount of a thing possessed, or the raw, abstract ability to choose from a dizzying array of possibilities, but in the quality of a life lived.

The Marxist-tinged accounts view social life as antagonistic, an ever-changing landscape of oppressive dominance between groups.

Like a virus that moves from host to host, the activist spirit spreads from cause to cause, seeking equalization of power, material differences, status and recognition through ever more coercive measures. Ironically, it achieves the opposite by spawning a growing web of regulatory, legal and organizational structures that concentrate power among large organizations and governments, the very cause of pernicious imbalances, stifling and smothering those whom it aims to uplift and protect. It is neglectful of the fact that life’s goods, both personal and cultural, are the fruits of agency, something that cannot be socially engineered, or ‘redistributed’. As the saying goes, equal at all costs — equally poor, unfree, unemployed and unfulfilled.

The problem with the postmodern view is that at its heart lies contradiction: creating and living by values that one believes to be fictitious, contingent and somewhat arbitrary, and yet also affirming and practicing them — a self-deception that is hard to sustain. The result is often cynicism, sarcasm and an ironic distance, supposedly the signs of superior wisdom, but really covers for a deeper malaise.

Quantity over Quality

Rather than pure progress characterized by quantities and abstractions, the unjust dominion of the rapacious west, or heroic relativism, we can have a much more nuanced view.

Advances in science and technology enable the skillful manipulation of the natural world to achieve things that were unthinkable to previous generations, from wealth and health to a capacity for — but not necessarily achievement of — richer, more fulfilling lives.

Our institutions have developed to such an extent that we are protected from the great harms and evils that were more commonplace in times when life was more dangerous, resources were more scarce, and collective wisdom was more diffuse.

Without the scaffolding of institutional wisdom and stability — the inheritance of civilization — we wouldn’t be able to replicate and improve upon successes with each passing generation. Nor would we have the connection to a past, and an ideal of the future, which are essential to human life.

Yet, the boons of progress have come at the expense of a proper understanding of human dignity and the inherent value in things, in favour of injections of artificially induced highs and a shallow vision of life.

Our civilization has lost the sense of the true, the beautiful and the good. The zeitgeist is characterized by a paradoxical turn inwards. Subjectivity determines every person’s ‘truth’ and as such, is the most important value in our society, yet we collectively refer to value judgments as mere preferences, or tastes because they are supposedly subjective.

Blotches on paper are called art. Choices are deemed good if they are the product of crude autonomy, whether they lead to health, wisdom and fulfilment over time, or temporary flashes of excitement in the pan and isolated, lonely, adult children later in life.

The cultural declines evident in stale, empty, repetitive forms of life that valorize work and consumption more than family and friendship are recognizable to all. Signs, to be sure, that have been seen many times before in Greece, Rome, China, and Mesopotamia at their apexes – civilizations who slowly decayed and imploded from within, under the weight of their own contradictions. Unlike Yuval Noah Harari’s vision of Homo Deus, we may be entering a state of cultural devolution, as our upright homo-sapiens begins to slouch into her desk chair, hunched over a screen — homo-docilis.

Characteristic of our age is a truncated vision of the good life stemming from a narrow view of what counts as knowledge, how we know it, and the extent of our powers of reason, confined to the physical and the mathematical, for instrumental and theoretical purposes alone.

Consequently, we’ve adopted the technocratic approach to problem-solving in every domain and even to the art of living itself, conceiving of happiness and fulfilment as outcomes that require the inputs of the rational application of technique and choice in piecemeal fashion.

The perspective is ubiquitous. In economics and public policy, what is thrift and saving, when you can finance growth by debt-leveraged consumption? Having trouble sleeping? Don’t change your habits, take a pill. Trouble finding a mate? There’s pornography for that. Balancing family and a career? Freeze your eggs and put off marriage. Need to get out of the hustle bustle? Listen to some nature sounds and practice mindfulness for a few minutes a day. Want to learn about something? Read the summary, watch a video, or ask google.

By finding technocratic fixes to every problem, the underlying causes are swept under the rug, stymieing the cultivation of the very things we are ultimately trying to foster — personal character, and social capital. Simply, they cannot be had without commitment to friends, family, place, purpose, a belief in and practice of morality as standards discovered outside of one’s self, including a sense of, and devotion to that which is transcendent.

Much of this is found and nurtured in a community. It is a word used so frequently today, not because it is descriptive of any given situation, but because it is aspirational. There are so few genuine communities to speak of — just a vague sense of sharing characteristics with members of a group that one will never see, and who probably, one does not even engage in shared projects with. The irony is that seeking them online or at a distance further undermines their quality, and the ability to make and maintain lasting connections.

Progress is much more than just outcomes — it is the quality of life lived. In this regard we are declining at an accelerating rate and our ability to respond to the challenges of life is dependent upon our personal and social capital, which are being eroded by technocracy, restless and misguided activism, and libertine liberalism. While there is a story of continuing technological progress, that is not the case insofar as human wisdom is concerned. More and more, there is less wisdom to be found from the latest book by a New York Times columnist, top academic, or entire University departments than there is around a Bingo table at a retirement home.

It is really this worldview that holds such power over us — the delusion that salvation lies in the application of technical rationality for instrumental purposes. To be cured of it, people do need a new common-sense revolution but not of the public policy sort. A true return to the obvious, and the everyday. As we are all fatigued by polarization and isolation, it means stepping away from toxic spaces online, spending time with family and friends, and those who don’t think like you or share the same background, in places where different social classes sit with one another, side by side — places of worship and community groups are good places to start.

We can build on the strengths of the Enlightenment, address the wrongs of the past, and attempt to quell the spiritual malaise of this era of decadence and relativism, but it requires a little less of the social engineer, the radical, the yuppie and the hippie, and a little more back to basics.

In this era of Promethean self-assertion, we must ask ourselves if our flourishing is dependent upon our ability to improve upon our natures, or whether it comes from accepting, celebrating and developing ourselves within those natural limitations? In this age more than ever, we risk emphasizing the former at the expense of the latter, missing the forest for the trees.

Recommended for You

Canadians are drinking the least amount of alcohol in the last 20 years on average: Statistics Canada

Auston Matthews doesn’t owe Canada a thing

The great fiscal–economic decoupling of Alberta

If Canada wants stronger communities, it must make volunteering easier

Comments (0)