The Hub launched with a core mission of getting Canadians thinking about the future. We’ve been stuck in the doldrums, pessimistic and polarized, for too long. To lay out a roadmap for the next 30 years of Canadian life, we asked our contributors to pinpoint the most consequential issue, idea or technology for the country in 2050. This series of essays by leading thinkers will illuminate Canada’s next frontier.

Any noteworthy technologist or futurist would agree that by 2050 it’s extremely unlikely that the world will be operating on a U.S. dollar reserve system. The Chinese and the Russians won’t allow it, and frankly, the limitations of this old monetary system have been showing for decades already.

Since 2009, the world has watched as Bitcoin, Ether, and other notable cryptocurrencies have grown in relevance and technological sophistication. Putting aside the obvious cynical perspectives about this new frontier of money, it stands to reason that in an increasingly borderless and digital world, we will be operating on a borderless and digital monetary system.

I’m not suggesting that sovereign monetary policy will not exist in 2050, or that we’ll be buying our groceries in Bitcoin, but I do think we will incrementally see a shift between now and then towards a system of money that is backed by assets that are globally accessible, digitally transferable, and provably scarce. The likely candidate is Bitcoin, along with a small number of others.

It’s easy to roll your eyes at this idea. But bear in mind that 2050 is three decades from now. That’s 20 percent of the age of our country. In the past three decades, technologists have invented the personal computer, the internet, the mobile phone, online video and music streaming, social networks, and so much more. There are all concepts you definitely would have rolled your eyes at in 1990.

Digital money is the next frontier. And its impact will be unevenly distributed across the world.

Countries who recognize this trend before their peers will be the first to stake their claim on these newly discovered gold deposits of the 21st century.

In other words, the first country to acquire one percent of the total supply of Bitcoin will likely be the only country ever able to do so. As with discovering the world’s rarest mineral deposit in your soil, Bitcoin has the power to make poor countries rich and rich countries irrelevant.

This policy could be responsible for the single greatest lift in Canadian wealth in our history.

In today’s dollars, acquiring one percent of all Bitcoin would likely cost between $50 billion and $250 billion to accumulate (the range is broad because this type of purchasing power has never come to Bitcoin, so it can have an enormous impact on its value).

And although 2050 may seem far away, this race has already started. Within this decade, we will undoubtedly see which countries are leading the pack and staking their claim. Although I’m convinced this list should include Canada, I’m skeptical that it will.

But let’s be optimistic for a moment. Let’s imagine that we had the guts to venture down this path as a country. How would we even get started? How would we approach this responsibly?

Before exploring the feasibility of this idea, it’s worth noting that both Mark Carney, a well-known Liberal and former governor of the Bank of Canada and Bank of England, and Stephen Harper, Canada’s former Conservative Prime Minister, have hinted at this being a direction worth exploring for the global monetary system.

Although they may not be as explicit in their vote of confidence for Bitcoin, I blame that more on their age and relative disconnect from the world of technology. Although I’ll give an honourable mention to Mark Carney for having recently joined the Board of Directors of Stripe — arguably one of the most important financial technology companies in the world today.

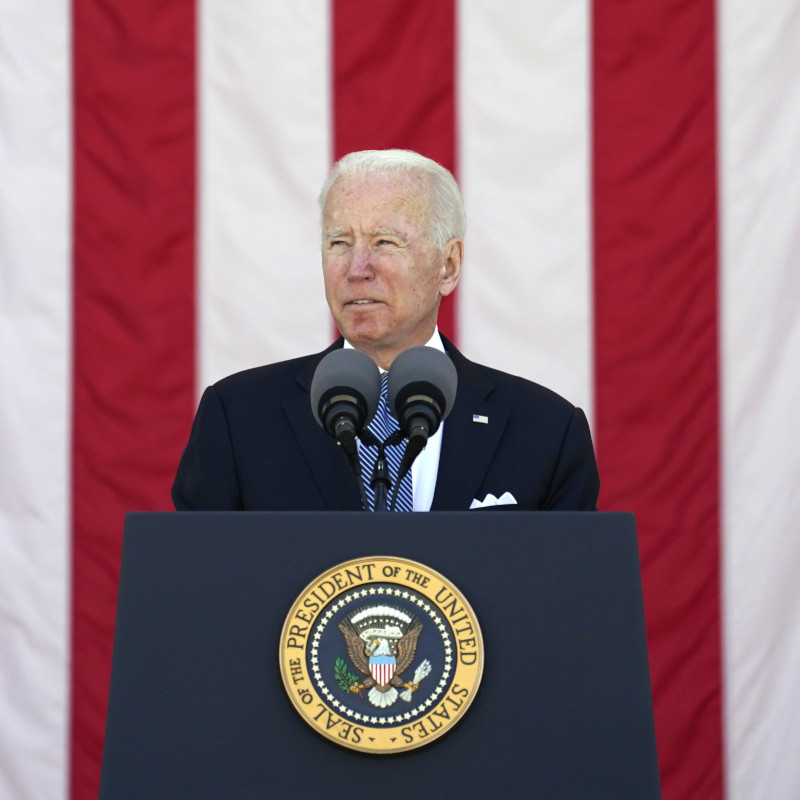

Meanwhile, U.S. President Joe Biden has asked the IRS to start cracking down on the American crypto industry, likely causing a significant slowdown in their national adoption. This could lead to a huge opportunity for Canada to differentiate itself and attract a growing industry to its shores.

In terms of simple policy, there are likely many paths to consider, but two that seem like obvious low hanging fruit would be, one, the creation of a Canadian Bitcoin sovereign wealth fund and, two, a tax incentive for Canadian individuals and corporations to add Bitcoin to their balance sheets.

Part one could be accomplished with a nominal budgetary commitment of 0.5 percent of national expenditures each year going to accumulate Bitcoin into this sovereign wealth fund.

Part two, for individuals, could be accomplished with a “little brother” to the TFSA program designed specifically for individuals to accumulate up to $5,000 in Bitcoin each year in a tax-free account. This would have the opposite effect of what is transpiring in the U.S. where citizens are being penalized for owning Bitcoin.

Similarly, for corporations, a capital gains exemption policy could be created, limited to a certain amount of Bitcoin value acquired each year. Say $50,000 for small businesses and up to $5 million for larger businesses.

Within one year of passing this policy, Canada and its citizens (both individual and corporate) would likely control more than 0.5 percent of the global Bitcoin market, which is roughly proportionate to our population as a percentage of the world. Within years two to five of this policy, Canada would have moved beyond one to two percent of Bitcoin ownership.

What excites me most about these ideas is that they’re intentionally different from American policies in this area. If we want to start outperforming our southern neighbours, we need to be willing to make different bets.

By conservative estimates, after year five, this policy could be responsible for the single greatest lift in Canadian wealth and GDP per capita in our history. By the end of the decade, Canadians would, on average, be the wealthiest people in the world, unblocking us to accelerate our history of world-leading innovation, enable our entrepreneurs to take worthwhile ambitious risks, provide much needed capital to families and small businesses, and play an incredibly important role in improving wealth inequality.

By 2050, Canada would have cemented itself as the small but mighty country to be reckoned with in economic might.

The impact of cryptocurrencies on the world economy are still underappreciated, even though they now represent an economy the size of Canada’s — and growing.

Some countries will see this change as a threat to their sovereignty, others will see it as an opportunity to change their fortunes. I hope Canada can prove itself a frontier nation once again.

Recommended for You

Canada’s health-care status quo is ‘nonsensical’: What’s behind Alberta’s reported health-care reforms?

Can David Eby be brought onboard an oil pipeline? Two former NDP staffers weigh in

‘A new industrial revolution’: Meta’s Kevin Chan on why an open approach to AI could be transformative for Canada’s economy

Overstuffed and unnecessary: It’s time to downsize the House of Commons

Comments (0)