Progress entails, as we have seen, destruction of capital values in the strata with which the new commodity or method of production competes. In perfect competition the old investments must be adapted at a sacrifice or abandoned; but when there is no perfect competition and when each industrial field is controlled by a few big concerns, these can in various ways fight the threatening attack on their capital structure and try to avoid losses on their capital accounts; that is to say, they can and will fight progress itself.

– Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy

A recent Hub Dialogue between Robert Atkinson and Sean Speer championed the imperative of scale in Canada’s private sector. This discussion, however, considered issues of enterprise scale out of context. It’s true that large companies have many scale advantages for themselves, their shareholders, and their employees. But Canada’s biggest businesses have, at best, found no way to contribute to arresting the country’s declining economic dynamism. At worst, their dominance may contribute to its ongoing fall.

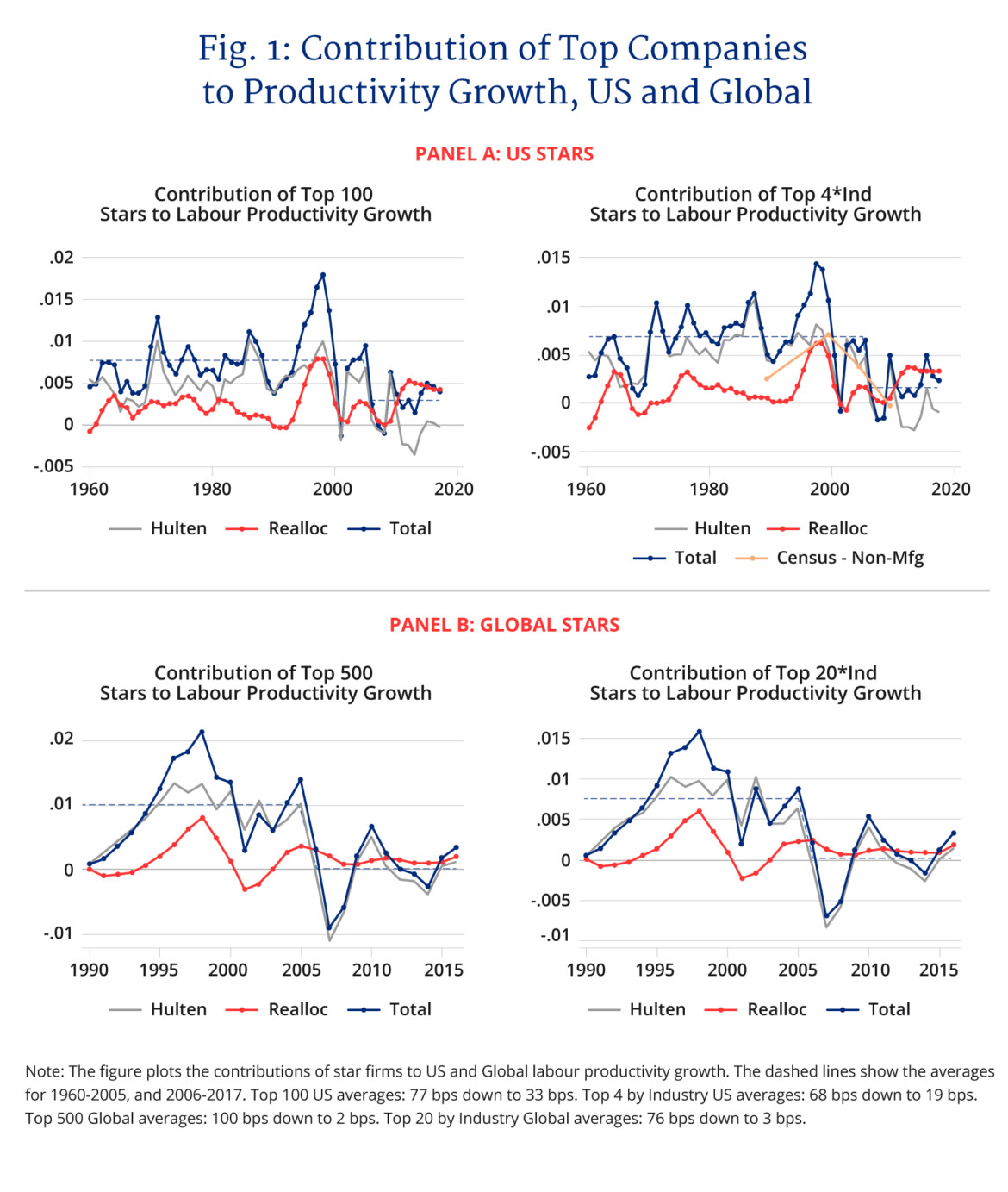

When you dig a bit deeper into the data, the glamour of bigness wears away quickly. A recent NBER working paper, “Some Facts on Dominant Firms,” outlines how the social and economic returns to scale and dominance have been shrinking for some time. Top firms contributed meaningfully to productivity growth in the postwar period, but, since 2000, they have not become larger or more productive, and their contributions to aggregate productivity growth have decreased dramatically.

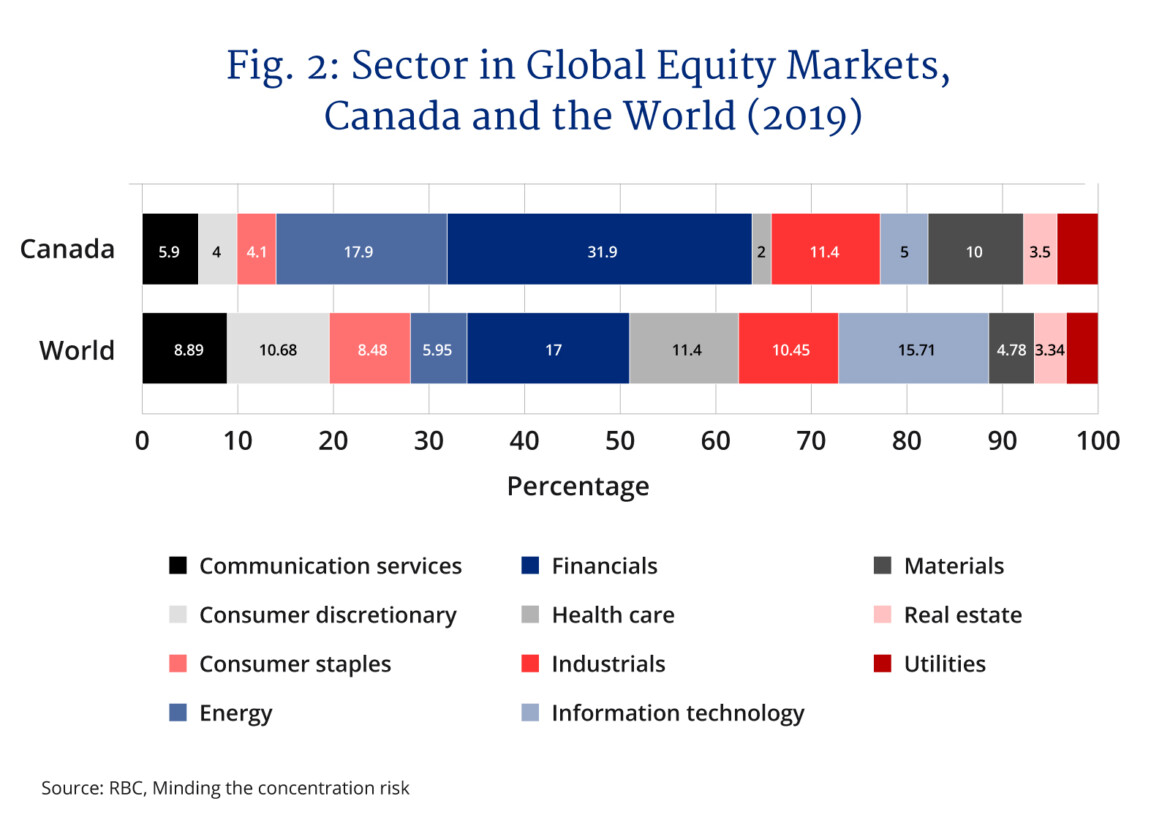

Returns to scale are particularly high for companies in high-tech and intangible sectors. These sectors, which have been responsible for remarkable broad-based gains in productivity over the past several decades, have also led equity markets in growth for a long time. Regrettably, Canada has among the smallest representation in these sectors among advanced economies—below global equity market averages and well below comparator nations.

And it may not just be which sectors dominate Canada’s economy but how concentrated they are. A 2019 SSRN paper “Are Industries Becoming More Concentrated? The Canadian Perspective,” finds that Canadian firms have also exhibited signs of consolidation.

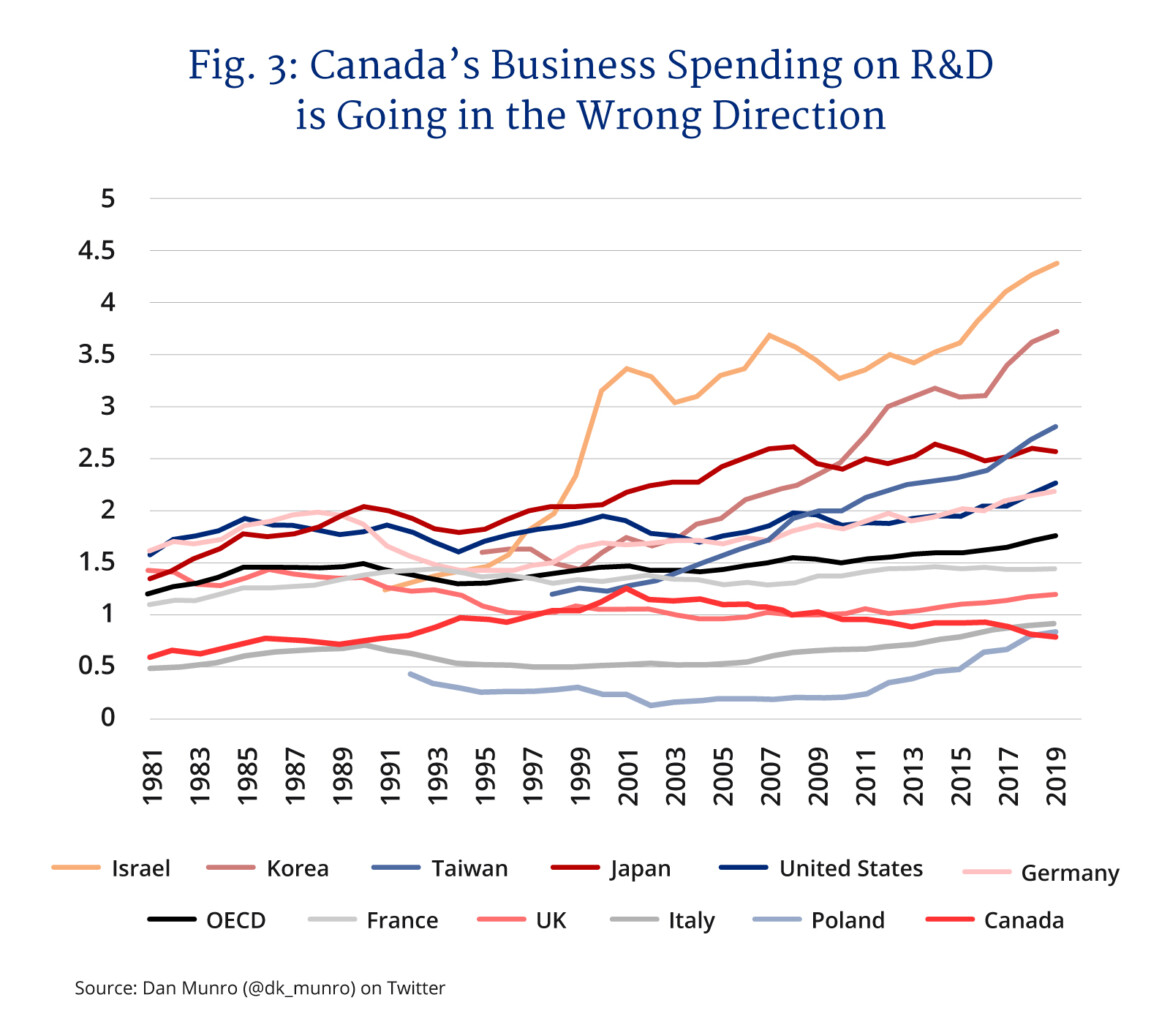

If there is a problem with big business in Canada, it’s not that big business is “too big.” After all, in most countries, large companies are disproportionately responsible for spending on research and development, and Canada is an advanced economy with plenty of large companies. So what are Canadians to make of a continuing two-decade decline in business and enterprise R&D spending (now among the lowest in the OECD), while every comparator country has seen meaningful increases over the same period?

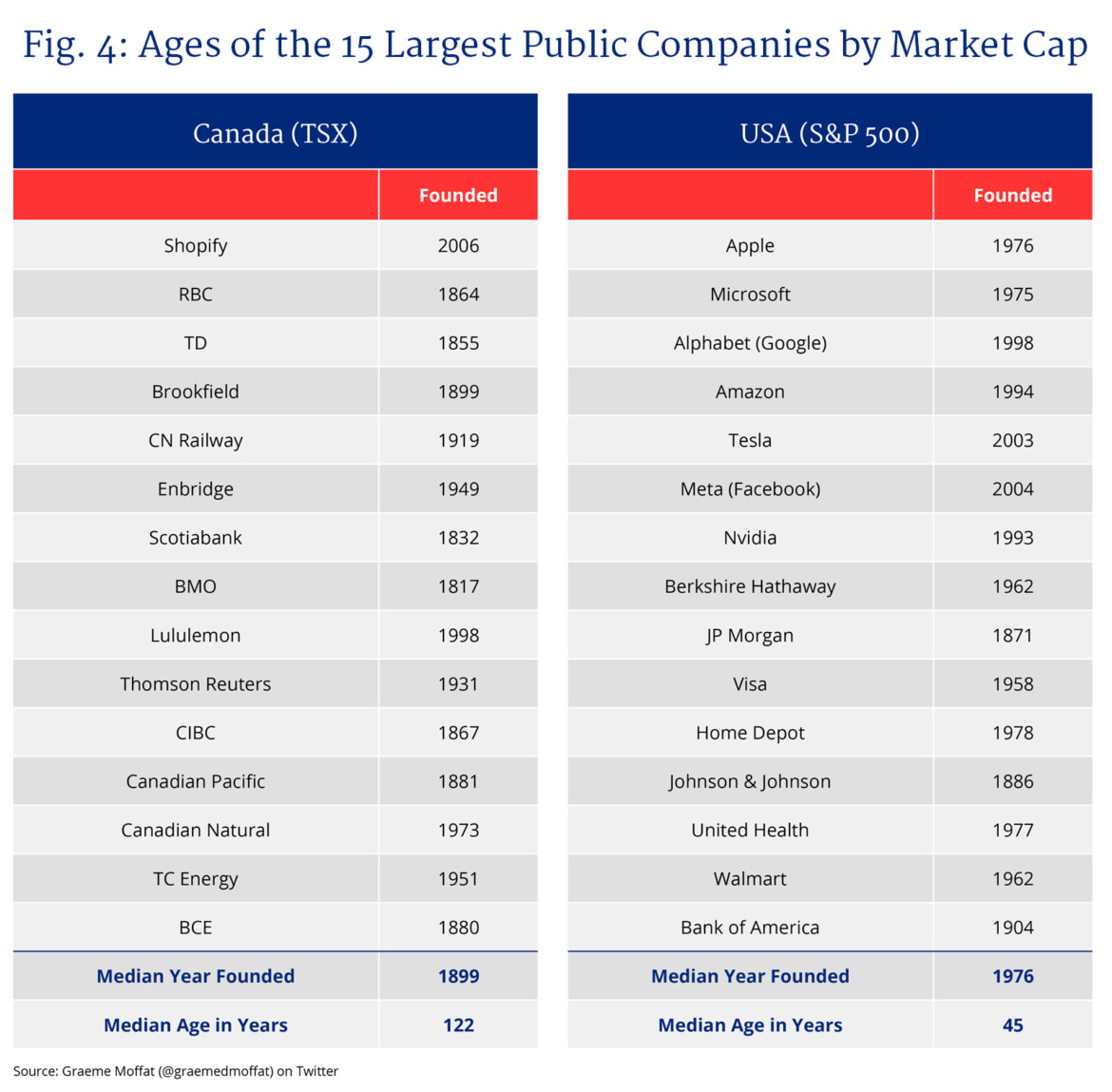

One answer might be to examine the composition of the top of Canada’s equity markets, which are dominated by old financial firms and resource companies.

For emphasis: the median age of Canada’s fifteen largest public companies is 122 years. Canada’s Fathers of Confederation might have been shareholders in many of today’s largest Canadian companies. Many of the largest U.S. public companies, in contrast, are younger than their average shareholder.

Is dynamism important? Of course it is. What should Canada make of a 2021 Toronto Stock Exchange that would be largely recognizable to a Bay Street broker from 1921?

We should, of course, want companies to reach scales that benefit consumers, investors, and Canadians in general. Yet those returns to scale are not just hard to find in R&D spending but in market metrics as well.

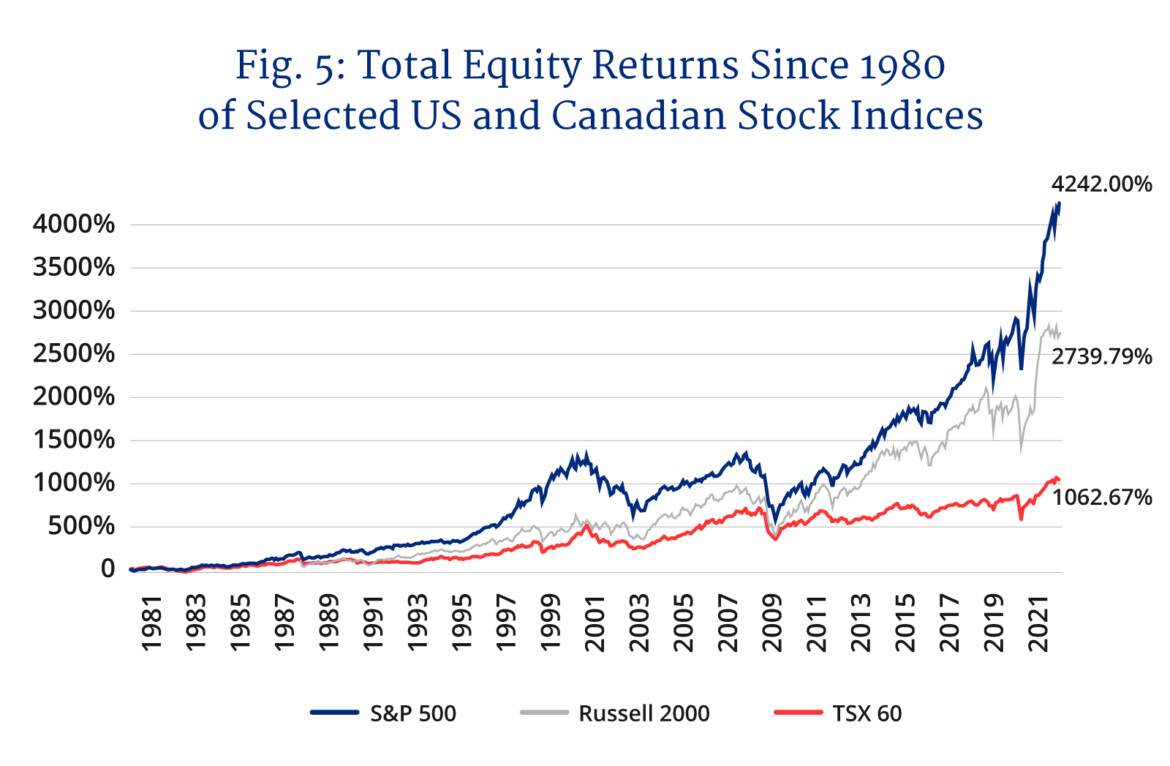

Consider the return on $100 invested in equities in 1980: if you chose an index of Canada’s largest public companies (the TSX 60), at the end of 2021 you’d have just over $1000. Not bad, certainly, but disappointing compared to the $2700 you’d have earned if you’d invested that same $100 in the mix of small and mid-cap U.S. companies that comprise the Russell 2000 index. And your returns are embarrassing compared with the $4200 returned by the S&P index of the 500 largest U.S. companies.

The 500 largest U.S. companies meaningfully outperform the next 2000 small and mid-caps, so there are obvious returns to scale. This raises an important question: why aren’t there equivalent returns to scale in Canadians’ retirement portfolios?

From the modest body of research that does look at competition issues in Canada, what do we know about the competitive environment? Discussions of “competitiveness” framed in terms of Canada’s poor performance relative to peer countries may miss links to domestic competition. One popular view holds that Canada cannot afford strong domestic competition policy and that our firms require special accommodation at home (in the form of lax enforcement of domestic competition laws) in order to compete effectively abroad. This thinking is flawed: Canada’s low-competition environment and concentrated domestic sectors reduce productivity and stifle the growth of new Canadian growth champions, and our markets may need more competition to help newer companies achieve scale.

Michael Porter famously addresses the importance of domestic competition in Competition and Antitrust: A Productivity-Based Approach and The Competitive Advantage of Nations:

“When local rivalry is muted, a nation pays a double price. Not only will companies face less pressure to be productive, but the business environment for all local companies in the industry, their suppliers, and firms in related industries will become less productive. This demonstrates in particular the danger in arguments about the creation of ‘national champions’ in an industry in the home country in order to gain the scale to compete internationally. Unless a firm is forced to compete at home, it will usually quickly lose its competitiveness abroad.”

Despite disquieting indicators of the persistence of large, old firms, falling business investment, capital flight, and declining corporate R&D, recent consolidation trends in Canada are not well characterized. We need a better understanding of the dynamics and implications of concentration in Canada, especially in a post-pandemic recovery.

Competition Commissioner Matthew Boswell recently delivered a scorching address to the Canadian Bar Association, noting: “Money alone will not solve Canada’s competition challenges, which include high levels of business concentration, weak business dynamism and widespread regulatory barriers to competition.”

Economist Stephen Tapp explored the “start up slow down” in a 2015 Policy Options piece, wherein he warned Canadians that the research shows Canada has seen declining entry of new firms, fewer start-ups, and no increase in job turnover relative to past performance.

When it comes to firm size, “big” must be recognized as a means, not an end. Big can be “beautiful“ if it enhances growth, if it increases productivity, if it raises wages, if it lowers costs to consumers, if it grows exports, and if it delivers prosperity to Canadians. When small companies grow into mid-sized companies, and mid-sized companies grow into large companies, employment and productivity increase markedly, as Viet Vu, Steven Denney, and Ryan Kelly recently demonstrated in their report on Canadian scale-up companies. In fact, productivity gains seem to be far more concentrated in fast-growing mid-sized companies than in large ones, at least in Canada.

The next 50 years will see the advent of new industries that will spawn large, globally competitive companies in sectors including virtual reality and the metaverse, electric vehicles, nuclear power, orbital industries, biotechnology, and others. Given that Canada’s largest companies have barely turned over in more than a century, and given our historic and ongoing weakness in intangible-dependent sectors, our participation in and prosperity from these growth sectors is anything but guaranteed. We must get our act together and determine what forms of competition and economic policy will allow Canada to grow into something more than a land of mortgages and minerals.

We deserve a comprehensive review of the Competition Act, much more research on the dynamics of competition and concentration in the country, and a real discussion about business dynamism. Canadian equity markets have underperformed balanced international portfolios for more than four decades.

Canada’s present large-scale enterprises have collectively failed to change the country’s downward trajectory in productivity growth. If present (or larger) enterprise scale is the solution to this country’s economic doldrums, it falls to advocates of big business to demonstrate not just that large companies pay higher wages, but how Canada’s large companies can drive real growth beyond what the country has achieved in the past few decades. It’s nearly 2022, and despite international consolidation and ever greater scale in the beverage industry, Mexicans still don’t drink Molson.

We should have more scale-up and growth companies, and we should have big businesses with returns to scale that benefit consumers, investors, employees, and Canadians more broadly. But let’s acknowledge, first, that what we’ve got now has driven us through decades of low capital investment, declining R&D spending, and crummy equity returns.

Big businesses may yet set Canada on a new growth trajectory. Those big businesses will almost certainly be newer and younger big businesses, though. If past performance is any indication, new dynamism won’t come from the old low-growth, low-innovation, low-tech big businesses that have dominated Canada’s markets for too long.

Recommended for You

Is Canada an easy place to do business? The World Bank says not really

What Canada must get right in its AI strategy: DeepDive

‘The world is not going to eat less meat’: Bruce Friedrich on how lab-grown meat could save the planet

Why AI governance needs the moral vocabulary of the oil patch