“Defund the CBC.”

It’s the one line that never fails to elicit applause in a room full of Conservative voters. And, for all the discord that’s marked the Conservative Party leadership race so far, it’s one thing that the contenders seem to agree on.

Pierre Poilievre regularly leads “defund the CBC” chants in his packed rallies; Leslyn Lewis has called CBC an “arm of the Liberal government”; and in the leadership debate Roman Baber went so far as to compare the national broadcaster to Soviet newspaper Pravda. Former party leader Andrew Scheer later riffed on Twitter that “[at least] Pravda never pretended to be independent”.

Of course, these attacks refer to CBC News, just one of the national broadcaster’s many divisions, and its perceived pro-Liberal editorial bias. Nevertheless, by attempting to delegitimize one of Canada’s most venerable cultural institutions, leading Conservatives are turning a blind eye to the important historical role the CBC has played as a shaper of Canadian popular culture, an outlet for Canadian stories, and an incubator of some of the world’s most elite musical, theatrical, and behind-the-camera talent.

Thanks in no small part to the CBC and other publicly funded cultural organization, Canadians punch above their weight in virtually every facet of the entertainment industry. Three of the top ten most-streamed recording artists of the 2010s were Canadians.1Canadian Invasion: Why Drake, The Weeknd And Justin Bieber Rule The Streaming World https://www.forbes.com/sites/zackomalleygreenburg/2017/06/14/canadian-invasion-drake-the-weeknd-and-justin-bieber-rule-the-streaming-world/?sh=648354d92408 CBC-produced sitcom Schitt’s Creek steadily grew into a global phenomenon over its six-season run, sweeping the comedy category at the 2020 Emmy Awards. Filmmaker Denis Villeneuve, who cut his teeth in Quebec’s heavily subsidized francophone film industry, landed one of Hollywood’s most sought-after projects when he was tapped to direct the latest adaptation of the classic science fiction novel Dune. The first installment of Villeneuve’s Dune saga, released last year, was one of the year’s biggest commercial and critical successes, despite the unwieldiness of its source material (some of Hollywood’s biggest directors have tried, and failed, to bring author Frank Herbert’s vision to the big screen over the years). These are just a few examples of how Canadians can be found at the highest echelons of global popular culture.

Canadians love to rattle off the names of famous people who hail from the Great White North (just ask my long-suffering friends down here in the states), but we are less supportive of the cultural institutions that create opportunities for Canadian artists in the first place. A good number of Canada’s biggest global celebrities would still be toiling in obscurity in a world without the CBC.

Insulated from the quarter-to-quarter financial pressures that face commercial broadcasters, the CBC can support projects that would never see the light of day in a free market. Again, take Schitt’s Creek, for example. What other television network would have green-lit an ostensible Arrested Development clone anchored by Eugene Levy, a sixty-something C-lister best known to American audiences as the dad who walked in on Jason Biggs violating the titular pastry in the 1999 teen sex romp American Pie? The series also took a few seasons to find its footing—time it likely would not have been granted from a commercial network.

Of course, there’s no intrinsic reason for Canadians to care about the international success of Canadian entertainers and made-in-Canada TV shows, especially when their global visibility has no discernible effect on how Canada is perceived by other countries. Drake and Justin Bieber may be household names all over the world, but this doesn’t change the fact that Canada is less globally relevant today than its been at any point since the end of World War II.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is regularly greeted by half-empty rooms at the United Nations and is openly ignored by other world leaders. Canada badly lost its bid for a UN Security Council seat in 2020, despite shelling out more than $10 million in a futile attempt to buy votes. Just last year, Canada was left on the sidelines of a blockbuster security deal signed by the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Once a widely respected middle power, Canada has been reduced to a minnow in the global food chain.

We have more than just national pride at stake; a Canada that’s out of sight on the world stage is also one that is out of mind. This is not a great place for us to be in an increasingly dangerous world. Russia has shown unequivocally (and violently) in recent years that it has no regard for the territorial integrity of its neighbouring countries. Putin’s next major play could be in the Arctic, a region where Russia has a number of unresolved territorial disputes with Canada. Even our “best friend” the United States will eventually look to the north once it starts to exhaust domestic reserves of oil, potable water, and other critical natural resources. Without a substantial reservoir of goodwill at its disposal, Canada will struggle to rally the global community to its side in a time of crisis.

Fortunately, Canada can look to another country for guidance on how to use our abundant creative talent to raise our global profile: South Korea.

South Korea and Canada are similar in many respects. The two countries have comparable populations and almost identical GDPs.2Country comparison Canada vs South Korea https://countryeconomy.com/countries/compare/canada/south-korea Much like Canada, South Korea is sandwiched between two Great Powers—it sits precariously between China and Japan and has a fraught history with both countries. Like Canada, South Korea would be badly outmanned and outgunned in the event of a conflict with one or both of its larger neighbors.

But South Korea has one crucial advantage over Canada: it’s pound-for-pound the world’s biggest exporter of popular culture today.

K-Pop, a uniquely infectious mishmash of EDM, hip hop, and R&B, among other musical genres, is enjoyed by over 150 million listeners worldwide. Dystopian Korean drama Squid Game was the single most streamed series on Netflix last year. The equally bleak Parasite took home four awards at the 2020 Academy Awards, including the Oscar for Best Picture (it was the first non-English language film ever to win in the category). Korean popular culture is now a truly global phenomenon.

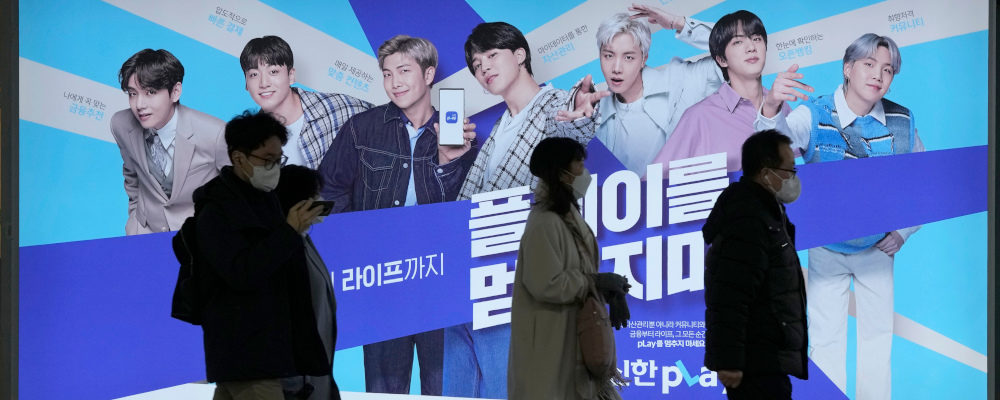

And there’s a lot more to the story than the superficial glitz and glamour. South Korea has channeled the popularity of its cultural products into abundant soft power, which it now exerts at both a regional and global level. For instance, in the fall of 2020, Chinese state media unsuccessfully attempted to “cancel” Korean boy band BTS over the group’s omission of China’s contribution to World War II in a speech they made to the New York City-based Korea Society. The campaign was abandoned after only a few days, once it became clear that state propagandists were no match for the Mainland China division of the BTS ARMY (note to readers: the acronym ARMY, which officially stands for Adorable Representatives for M.C. Youth, refers to BTS’ global fanbase). This was a nontrivial setback for a state media apparatus that’s accustomed to exerting its will against major global brands like the NBA. (BTS accompanied South Korean President Moon Jae-in to the UN General Assembly this past fall).

The so-called Korean Wave (Hallyu)3“The Korean Wave (Hallyu) refers to the global popularity of South Korea’s cultural economy exporting pop culture, entertainment, music, TV dramas and movies. Hallyu is a Chinese term which, when translated, literally means ‘Korean Wave’. It is a collective term used to refer to the phenomenal growth of Korean culture and popular culture encompassing everything from music, movies, drama to online games and Korean cuisine just to name a few.” https://martinroll.com/resources/articles/asia/korean-wave-hallyu-the-rise-of-koreas-cultural-economy-pop-culture/#:~:text=The%20Korean%20Wave%20(Hallyu)%20refers,literally%20means%20%E2%80%9CKorean%20Wave%E2%80%9D. that’s now sweeping the world did not happen overnight, nor was it the product of spontaneous coordination among private market actors. On the contrary, Hallyu is the culmination of a decades-long strategic initiative to cultivate global influence through the appeal of South Korean popular culture. The state has played an important facilitating role in this process by making substantial investments in the promotion of culture in the arts. In 2020, South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism received just under $5 billion USD from the government, a sum that amounted to nearly 10 percent of the annual budget.4South Korea gets record-breaking culture budget https://www.internationalartsmanager.com/news/arts/south-korea-gets-record-breaking-culture-budget.html The Ministry houses a specialized Cultural Content Office, which oversees the development of K-Pop, fashion, televised entertainment, and other key cultural products.

By comparison, the $1.4 Billion that the CBC receives from Ottawa each year (0.3 percent of the last federal budget) is small potatoes. The Department of Canadian Heritage, which oversees the promotion of “Canadian identity and values” via the arts, claimed just over 1 percent of the federal budget last year. The Heritage portfolio has not been helped by a series of bumbling ministers who have repeatedly bungled important files like the regulation of internet content (under the Trudeau Government, the only two qualifications needed to become Heritage Minister appear to be a seat in Quebec and great hair).

By failing to adequately support our cultural institutions, we are squandering one of our best assets—the dominance of Canadian performers on the stage and screen (and in the recording studio). The rise of streaming services has greatly reduced barriers to the global dissemination of Canadian content. Audiences in the United States and beyond have shown a massive appetite for lighthearted Canadian sitcoms and Toronto’s Caribbean-infused brand of hip hop and R&B. South Korea provides us with a blueprint for how to parlay the appeal of these Canadian cultural products into global influence.

The first step is to change the conversation surrounding the CBC and other publicly funded cultural organizations. Rather than dismissing these entities as a waste of taxpayer dollars, we should acknowledge them as critical incubators of soft power—a currency that’s more powerful than ever before in a global landscape dominated by social media and streaming platforms.

Rather than defunding the CBC, Canada should double down on supporting its cultural industries. We already have the creative talent to follow in South Korea’s footsteps; all that’s needed is stronger and more strategic support from the CBC, Heritage Canada, and other cultural agencies. Opening the public purse to channel the widespread appeal of Canadian cultural products into soft power would be one of the smartest and most cost-effective investments we could make in securing our place in the world.