The “Great Resignation”—the new buzzword referring to a surge in people quitting their jobs—gets no shortage of attention these days. In just the past month alone there were nearly 11,000 news articles mentioning it, according to Google.

Is this attention misplaced? Should Canadians be concerned?

Let’s look south of the border first. In the United States, over 4 million people each month quit their job—according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s approximately three percent of the entire labour force. That is a notable increase in the U.S. quit rate compared to pre-pandemic rates, which were closer to two percent, and close to double the rates that prevailed a decade ago.

In Canada, however, there is a very different picture.

It’s unfortunately tricky to easily compare—since our data is not as good—but we do have enough from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey to draw some conclusions.

In August, for example, approximately 0.5 percent of workers quit one job to start another (so they remained employed). This is slightly below the average pre-pandemic level of 0.7 percent. Add to this the less than 0.6 percent of workers who I estimate quit into unemployment or who left the labour force altogether, and only roughly one percent of workers left their job in August.I estimate this directly using the LFS Public Use Microdata File. The monthly average since 2017 is 0.3 percent who quit into unemployment or left the labour force. The higher rate in August is seasonal. The average monthly quit rate for all reasons from 2017 to today is one percent.

This is no higher than the normal pre-pandemic rates, and starkly lower than the U.S. If there is a Great Resignation, it can’t be found here.

But even if quit rates were rising, that shouldn’t itself necessarily be a cause for concern. After all, people leave their jobs for many reasons. Returning to school is a very common one, with over 200,000 Canadians leaving a job for this reason over the past year. Personal or family reasons are also common.

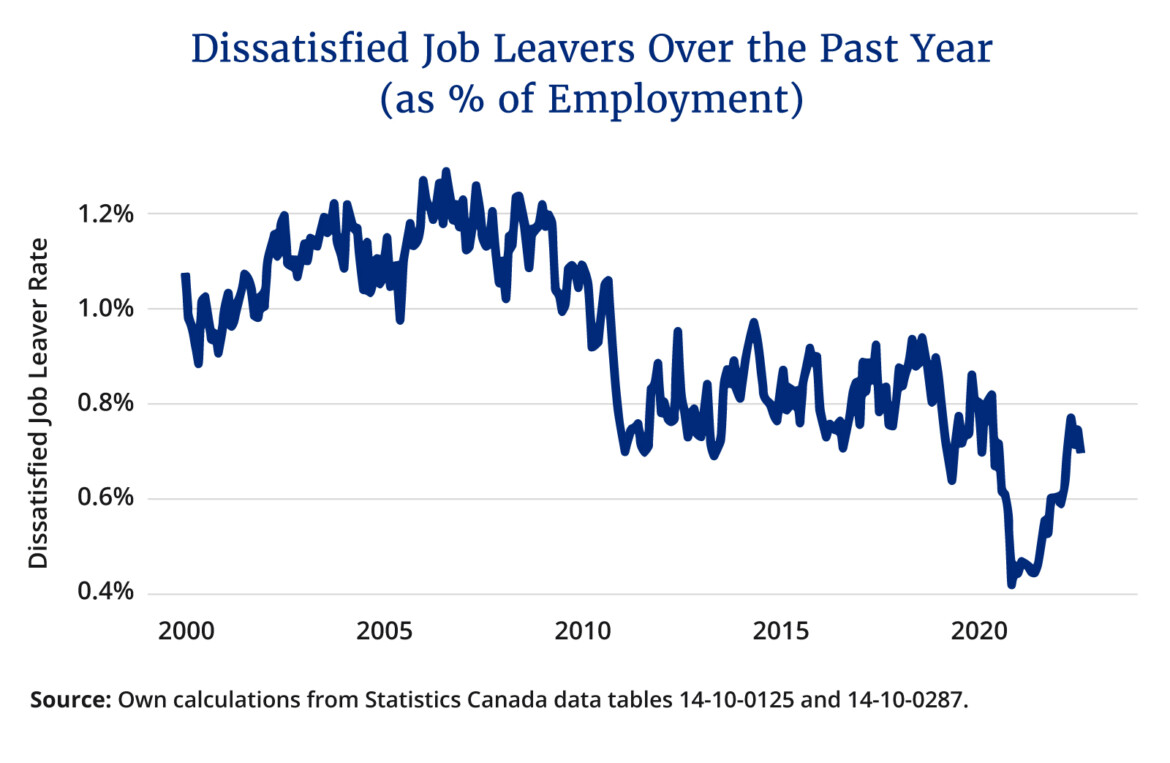

So consider another measure: the number of people who were so dissatisfied with their job that they preferred no work at all. We have pretty good data on this, as Statistics Canada regularly asks people without work whether they left a job in the past year for various reasons.

The results are striking.

Today, roughly 0.7 percent of the workforce left their job over the past year due to dissatisfaction with their job. This is below the pre-pandemic level, and notably lower than the 1.2 percent that prevailed before the financial crisis.

This is a clear improvement, but there might be risks this trend does not hold.

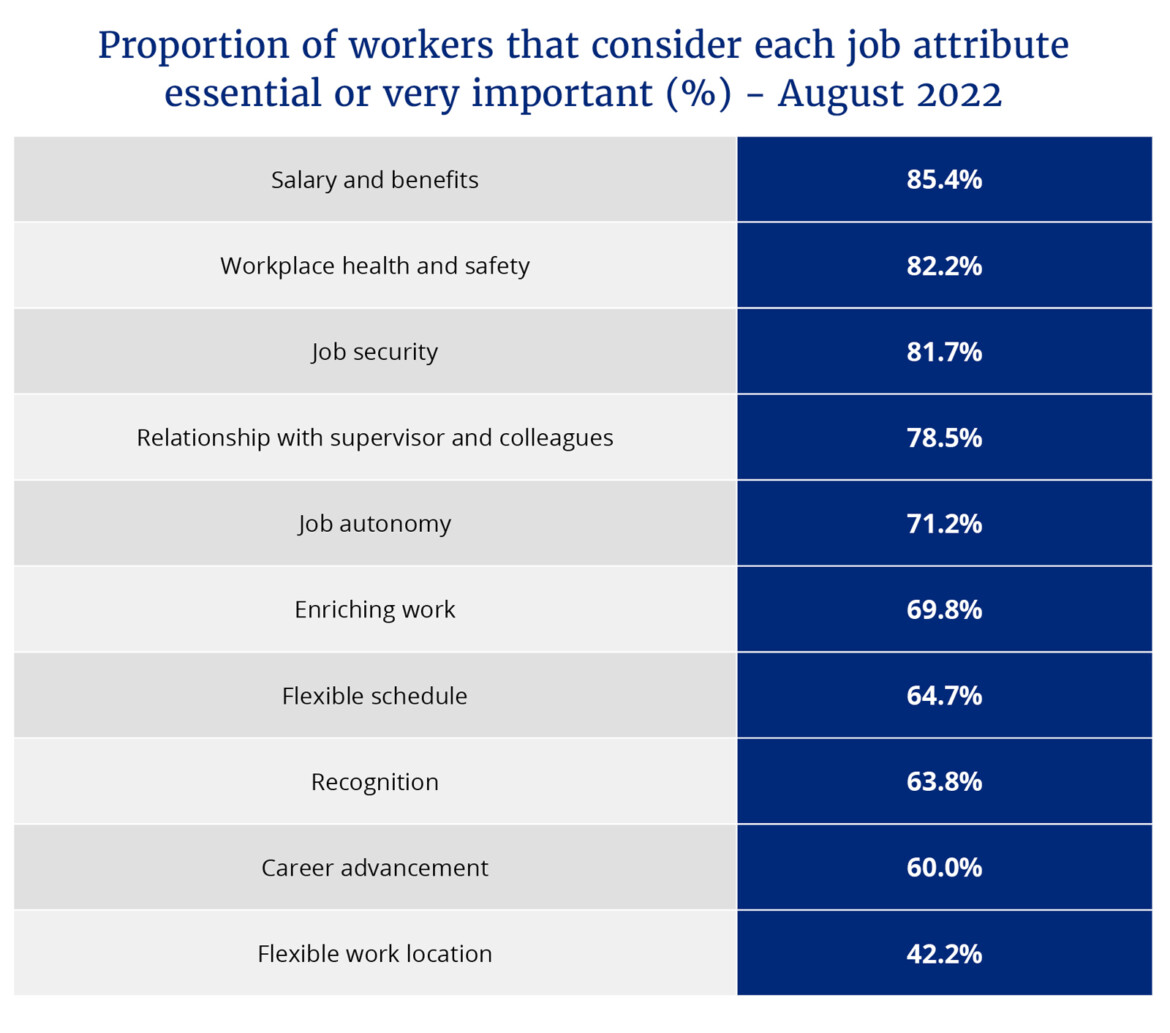

For example, Statistics Canada recently asked what employees considered most essential in their job. Not surprisingly, salary and benefits topped the list. So as high inflation continues to erode the real value of pay, job dissatisfaction and quits may rise. And while a flexible work location was not listed as very important by most workers, those workers that now normally work at least partly from home—which is just over one-quarter of workers today—a flexible work location was listed as essential or very important by over two-thirds. As an increasing number of employers seek to return to the office, job dissatisfaction—at least among some—may rise.

But there’s little evidence of this picture changing anytime soon. When asked whether people are planning to leave their jobs, Statistics Canada again finds no Great Resignation in sight.

Specifically, in August, they found that just under 12 percent of Canadian workers said they were planning to leave their job at some point over the next year. This is higher than the roughly 6 percent who said they were planning to leave the last time Statistics Canada asked the question in January. But is roughly consistent with the normal churn rate of one percent of workers leaving their current job per month. It is also far below the one-third of U.S. workers who say they plan to within the next six months, according to the Conference Board.

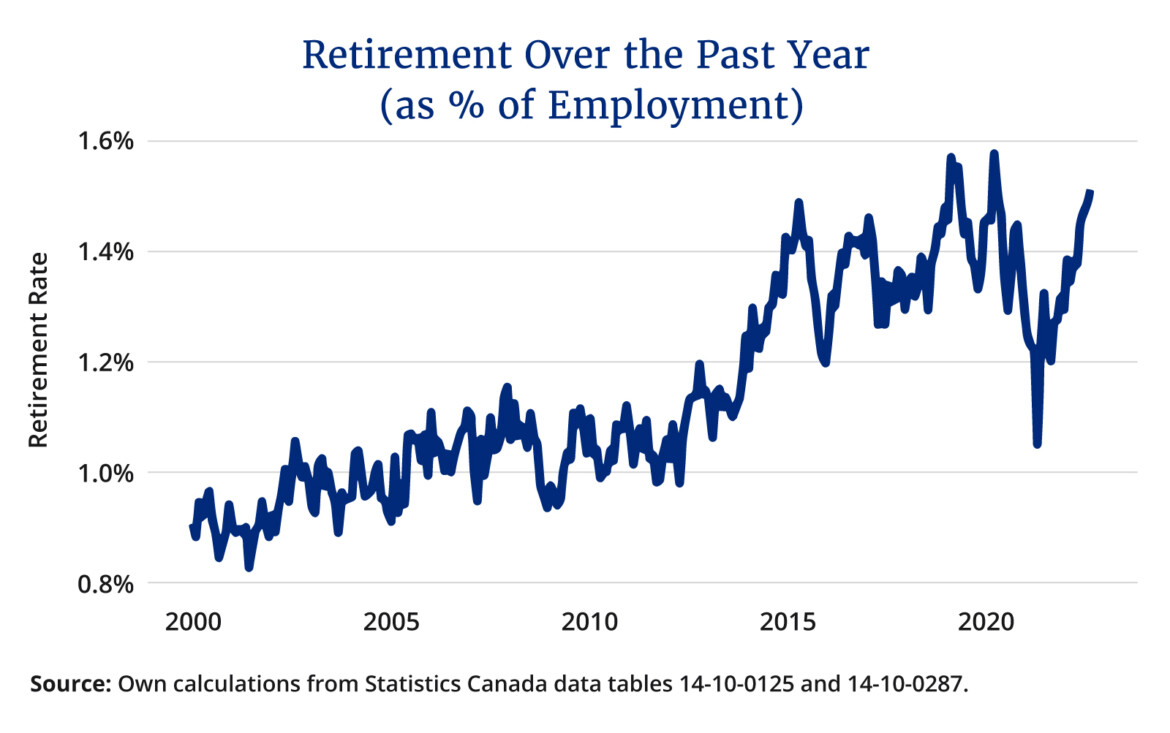

While Canada appears to be avoiding the Great Resignation, there is another potentially more serious source of concern. And one government may not be ready for: surging retirements.

Over the past year, the equivalent of 1.5 percent of Canada’s workforce retired. This is one-third above the roughly 1 percent that retired a decade ago. And it will only grow much larger from here.

This will have massive implications for Canada’s economic future. With a smaller share of its population working, overall productivity will be lower. For context, the latest projections suggest the national working-age population share may fall from its current 66 percent to nearly 62 percent by 2040. I estimate this would reduce the average annual rate of economic growth over this time by over 0.3 percentage points. This is large. Very large. In effect, it shrinks the size of Canada’s 2040 economy by more than 6 percent relative to a situation where there is no aging—that’s equivalent to nearly $170 billion today, or $4,500 per person.

It is the rising wave of retirements—rather than the not-so-Great Resignation—that deserves our attention.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes

Stephen Staley: Widespread deregulation is Canada’s golden ticket for economic growth

Stephen Staley: Canada’s economy is trapped in a tangled web of over-regulation. Growth and prosperity demands we cut ourselves free