About a year ago I was asked to prepare a short talk on the subject of socialism for my daughter’s social studies class. The lecture never took place, but it was written and shared with friends interested in their children’s education. One of them suggested recently that I rework the talk as an article.

I’m not a scholar of social sciences and only have personal observations and experiences from my time in socialist Russia—which I left at the end of its phase of “mature socialism” 40 odd years ago—and supported by my studies as a young man at a Soviet university where I formed my opinions, of which I make no secrets. I’ve believed for a long time now that parents and teachers have failed miserably in informing young people, who end up taking selfies under “Capitalism the Disease/Socialism the Cure” banners. I apologize if the reader finds the article too simplistic and its style too conversational, but it’s not for you, dear reader—it’s to be shared with your children. So here it goes…

At the university class called “Marxist-Leninist Economics”, we learned that “Socialism is a form of society where the government owns the means of production. As a result, there is no exploitation of a human by another human.”

That sounds reasonable. No good person really wants to exploit others, no one wants to be exploited. What are the “means of production”? These are the factories and farms, shops and restaurants—everything the economy actually consists of and where people work.

So, why shouldn’t the government own the factories and the fields? After all, the government is a big part of our lives. It is responsible for the economy, controls the borders, regulates banks and the environment, has an army to defend us, builds roads, and so on. Why not let it also own factories and fields?

There is an easy attractiveness in this idea: more equality (if no one owns the proverbial factory); no bosses and no servants; a heart-warming friendliness and fairness; and more moderate usage of resources (no one is cutting down primary growth forests and messing up the environment) because we are all in it together—equal friends.

It’s a lovely image and a great theory. So, what happens in reality?

Unlike theory, we don’t have to imagine reality. Canada is full of people who escaped from socialist countries. They came from Russia (the old Union of Soviet Socialist Republics), from the Republic of Cuba, from the Peoples’ Republic of China, from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea—all such grand-sounding names!—from Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and others in Eastern Europe, from Nicaragua and Venezuela in South America. “Escaped” is the key word here.

What went wrong in Russia and why? After all, socialist Russia lasted 70 years. At the time of its collapse, the Soviet Union had a population of over 300 million people. It was not a small-scale experiment.

So, back to history class: after the Great October Socialist Revolution (as it was called) of 1917 and the subsequent very bloody civil war, the Bolsheviks (later known as the Communist Party) seized power. All private businesses were nationalized. Their owners were executed, exiled, or jailed because they were understandably not keen on the idea of giving it all up.

Once the government owned all the means of production (factories, fields, stores, etc.), it had to develop massive country-wide systems to pay the workers. A huge job of equalization. All engineers with three years of experience would be paid 150 rubles; all teachers of high schools, 120; all nurses, 50, etc. I’m, of course, totally simplifying. But the main idea was “Equality”. The thinking went: once we are all relatively equalized within our work/education categories, and there is no longer an opportunity for personal financial advancement, we’ll all relax in our “living wage” paying jobs and live in a harmony of equals, with basic necessities supported by government subsidies.

But very quickly the Russians found that Karl Marx’s theory, while groundbreaking economically, was a total failure psychologically. It may sound patronizing or cynical, but people are different from each other. Some are very competitive, some are indifferent. Some are greedy, some are perfectionists, some are just lazy procrastinators. The conflicts between them are inevitable, even if they are all “equalized”. But the most important thing demonstrated by the Soviet experiment is that when the drive to succeed and outperform—to win, to excel—was removed as a motivational force, motivation went way, way down

If a class of students was to be told that no matter how well they perform on a test, they would each be given 75 percent, their incentive to work hard and study would disappear. Perhaps some people, driven by personality or interest in the subject, would continue to work hard and prepare for the test, but most people would study a lot less. Some wouldn’t study at all. Why bother, you’ll still get 75 percent. So the collective results of the entire class would deteriorate to well below the 75 percent that was promised.

That is what happened in socialist Russia. The incentive to work harder or smarter than the next person was largely removed. The production, the output, the whole economy went right down. Russia used to be a net exporter of grain to Europe. Over time it became an importer.

As university freshmen, we were sent to collective farms for all of September to help bring in the harvest. The vegetables rotted in the fields. Employment was guaranteed, and ten workers were hired to do the work of five. They were unmotivated and disheartened. Alcoholism became a national scourge. Politically appointed managers weren’t trying very hard either. Shortages of basic goods and produce became common and accepted, always blamed by the government-controlled media on weather, enemies of socialism, shortage of labour, supply chain disruptions, etc. To buy a car my parents had to sign up seven years in advance.

(As an aside, the Soviet Union didn’t have toilet paper until the ’60s since the government had other priorities, such as the arms race, having the best ballet company in the world, winning the most Olympic medals, and being the first in space.)

Also, theft and commercial crime became a real issue. Not everyone is content to be “equal”. (Karl Marx didn’t see it coming.) There will always be people looking for personal advancement, exploiting cracks in the system. They steal raw materials and sell them on the black market. They start underground businesses, which take resources. They divert manufactured products to private sales. All that further reduces the quality of goods, of food, of industrial projects. Corruption is the norm. Bribery is the norm.

Not trusting the Russian currency, the secret entrepreneurs converted their profits to dollars. The possession of foreign currency became a crime against the State, punishable by death. (Doesn’t sound very harmonious anymore, does it?)

The quality of industrial projects became so problematic that environmental disasters were common. Regulations were in place, but there was no capacity to enforce them and no capacity to fix the problems. Deteriorating pipelines spewed lakes of oil. Similarly for chemical factories. In one Siberian town, the air was so polluted that orange snow fell.

Remember, everything was owned by the government, and one government entity is hardly going to charge the other. As a proud industrial achievement, two rivers were diverted for irrigation of crops. As a result, the Aral Sea disappeared completely. The same goes for the fishing villages around it. Of course, these disasters were hushed up, victims silenced, media lied, foreign information was suppressed.

But then again: papers lie, TV lies, everybody lies. Public lying from necessity became the national character. Everyone was thanking the government, declaring devotion to the Party, denouncing politically-incorrect “enemies”, spouting slogans and common sense defying nonsense. Some actually believed in it, but many didn’t. Underground resistance started and took many forms. Unwillingness to live in that soul-deadening swamp of pretense was the primary reason for my emigrating.

Also important to note is that the power struggle in the government started on day one, if not before, and the same has happened in every socialist country. While you could not personally own the means of production (factories and fields) and become rich, you could still become very powerful in the ruling party and that’s when you’d get what you need, what you want. You’d shop at special stores, live in special apartments, stay at special secret resorts, travel abroad, etc.

A new ruling class appeared at the very top of the government. Compared to the rest of the people, its members got phenomenal privileges and enjoyed a phenomenal lifestyle. Basically, they owned the government while the government owned the country. Naturally, you’d have to eliminate your opponents, your comrades/competitors.

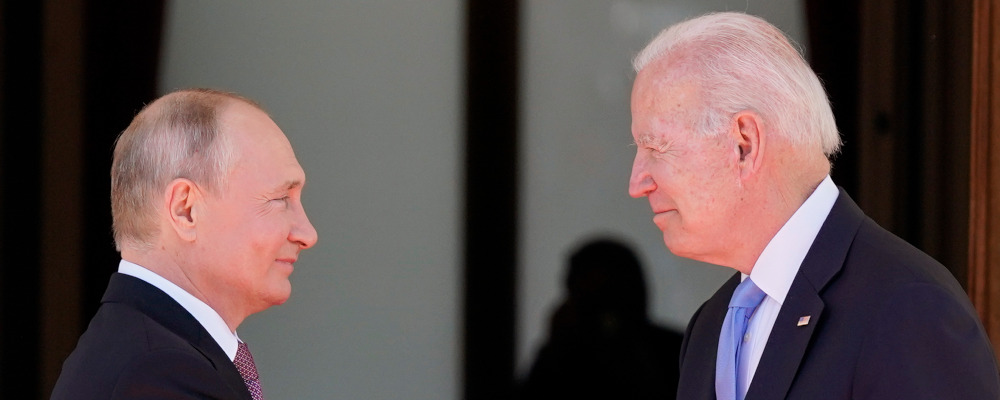

Democratic elections became a total sham. In socialist Russia, voting was mandatory, but every voting district had only one candidate. They were voted for by 99.9 percent of the people (funny how that works!), and invariably some kind of dictator rises to the top of the pile. Like Stalin. Like Putin in Russia now.

The stakes were very high indeed and the power struggle was totally vicious and bloody. Crimes against the State were invented. People were tortured to extract confessions. High-ranking government competitors got exiled or executed. Yesterday’s heroes became enemies of the people overnight.

Regular folks disagreeing with the party line or the ruling class privileges were thrown in jail, into gulag work camps, or, as they call it today in China, “re-education camps”. A great number of them died there. Public denouncements and public apologies for political errors became routine, as well as citizens snitching on their politically-incorrect neighbours. Millions of people were arrested on ridiculous trumped-up charges and executed. Children as young as 12 were shot. Luckily for me, the worst of that horror came to an end with Stalin’s death in the late 50s.

According to The Black Book of Communism written by a number of European academics, the Marxist-Leninist death toll in the 20th-century was as follows: China—65 million; North Korea and Cambodia—2 million each; Vietnam and Eastern Europe—1 million each; and about 3.5 million in Latin America, Africa, and Afghanistan. Professor Rudolf Rummel in his book Death by Government finds that from its 1917 inception until its collapse, the Soviet Union murdered or caused the death of 61 million of its own citizens.

To conclude: 70 years of socialist experiment in Russia was not a barrel of laughs. The country still has not recovered, and it’s hard to say when and if it ever will. Not just the economy, but the moral fabric of society was severely damaged.

Here in North America, which hasn’t lived through any of that horror, a young generation of misinformed revolutionaries now carry pro-socialist banners, cancel debates, denounce disagreeable writers and professors, and demand public apologies from podcasters and scientists. They have been fed some easy soundbites of Marx’s theory, and it speaks to their youthful idealism. Like the ones before them, they also want kindness, fairness, a clean environment, and a “brotherhood of men”.

They ask: why can’t the horrible mistakes be avoided? Why can’t we do the same equality thing, only better? Manage it better? Use computers?

Well, computers have improved, but human nature hasn’t changed. People aren’t wiser or kinder than the ones who went before you, who tried and perished. So beware. Think hard, and protect your great country.