As the Russian military continues its assault on Ukraine, casual observers no doubt view the ultimate outcome as inevitable given the reputation of Russia as a formidable military and world power.

Along with its nuclear arsenal, the Russian military machine is a behemoth compared to that of Ukraine, with 850,000 active-duty troops to Ukraine’s 200,000 and 772 fighter aircraft to Ukraine’s 69. Not to mention over 12,000 tanks to Ukraine’s 2,596. Indeed, the Global Firepower Index places the power of the Russian military second out of 140 ranked countries, with only the United States ahead of it and China right behind in third place.

Maintaining a massive military machine is ultimately an economic undertaking. In U.S. dollars, Russia is the fourth biggest spender in the world after the United States, China, and India, and just ahead of the United Kingdom. That an army marches on its stomach is a quote long attributed to Napoleon. In the modern world, that includes massive quantities of supplies and materials as well as the energy needed to power movement. All of this takes money. While Russia is a big spender with the military as its priority, it remains that the resources to pay for all this military infrastructure are not as abundant as one may think.

Of course, Russia is a large country with abundant natural resources and a skilled and relatively well-educated population that has made enormous economic strides over the last few decades. Yet, the legacy of decades of Communist rule as well as the growth of corruption in its economy during its transition after the fall of the Berlin Wall has hampered its full economic potential. While President Putin may have dreams of a Greater Russia that rivals the empire of the Tsars, in achieving this goal he is hampered by the same forces that held them back—a perennially weak economy that raises the opportunity cost of investing in military infrastructure. Every dollar spent on the military is a dollar less for productive investment geared to improving the lives of ordinary Russians and their consumption standards.

Nowhere is the weakness of the Russian economy more apparent than when simple comparisons using national output are made. Russia spends 4 percent of its GDP on its military, a higher share than the United States at 3.5 percent. It is also a much larger share than the rest of the G7, which ranges from 1 percent for Japan to 2.5 percent for the UK. However, it is applying that much larger share to a much smaller economy. According to the IMF World Economic Outlook Database, Russia’s economy is just over 1.6 trillion USD, whereas the United States has a 22 trillion USD economy. Even Canada, with a population less than a quarter that of Russia has a GDP that, at over 2 trillion USD, is 25 percent greater than Russia.

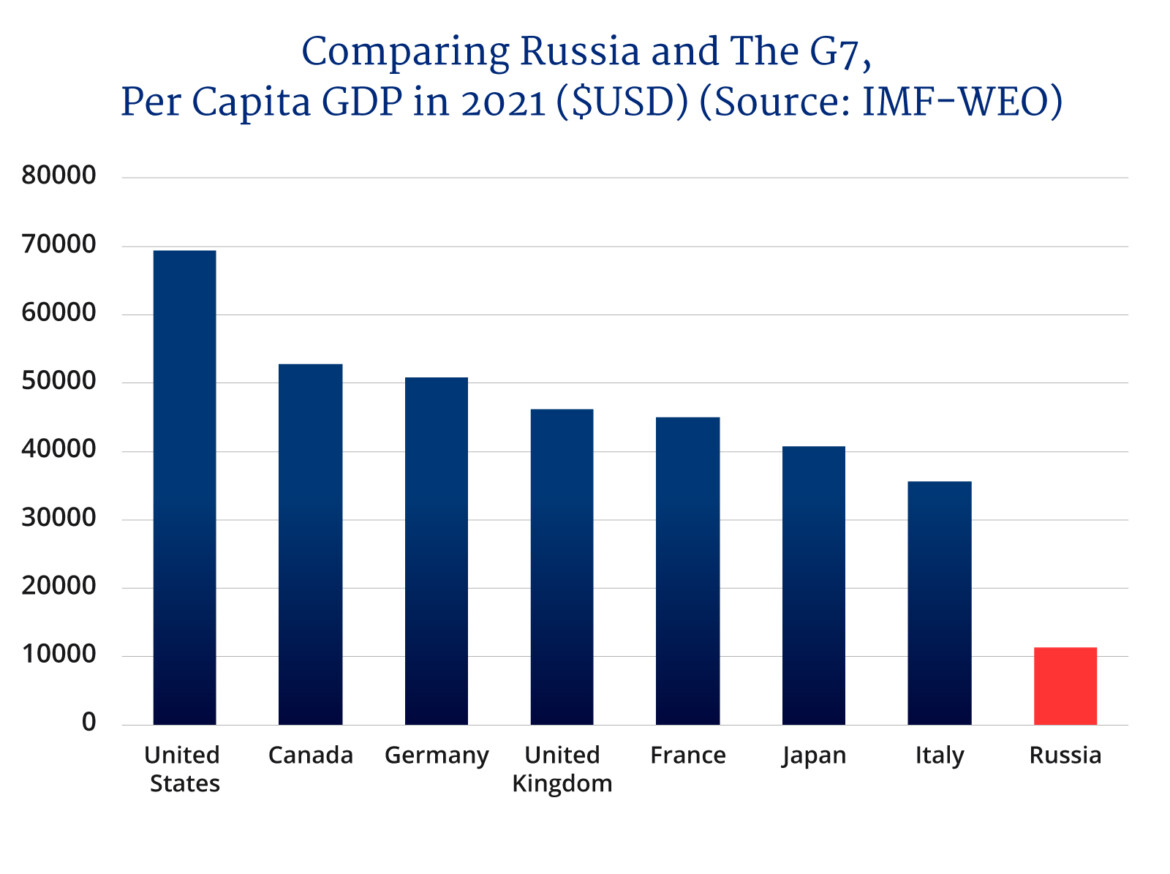

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The difference is just as stark when GDP per capita is examined. Whereas per capita GDP in USD is just over $11,000 for Russia, for Canada it is nearly $53,000. For the U.S. it is $69,000. Even the country with the lowest per capita GDP in the G7—Italy—comes in nearly three times higher than Russia at $35,000. It remains that Russia’s economy may generate massive natural resource wealth from its exports, but on a per capita basis, it has an income on par with China. Even former East European satellites of the former Soviet Union have often done better, as is the case with Poland which comes in at $17,000. And while Russia has created numerous billionaires and wealthy oligarchs, a low average per capita income in the face of such extremes also means that income inequality is high. Russia’s military might is at the expense of the economic welfare of the average Russian. This makes the toll that Western economic sanctions are taking more devastating—especially when the flight of foreign companies in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine threatens to reverse decades of economic progress.

The Russia of Vladimir Putin, like the former Soviet Union and the empire of the Tsars before it, is marked by a set of constant themes. They are all regimes characterized by the exercise of autocracy, the use of a secret police security apparatus to monitor dissent, and an expansionist foreign policy. To these themes can be added another: a chronically weak economy that fails to meet the material needs of the average Russian on par with the rest of the developed world. In the end, this economic failure provided the seeds of the 1917 Russian Revolution that ended the rule of the Tsars and the productivity lag that sealed the end of the Soviet Union. As Putin continues his quest to make Russia great again, he is likely to meet a similar fate.

Recommended for You

Gili Zemer and David Mandel: We are Canadian Jewish parents. The Toronto District School Board has failed to protect our kids

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes

Stephen Staley: Widespread deregulation is Canada’s golden ticket for economic growth