We recently published analysis at The Hub on how Canada’s current labour market recovery is fundamentally a government-centric recovery.Canada’s ‘roaring’ recovery is not as robust as it seems https://thehub.ca/2022-07-08/sean-speer-canadas-roaring-recovery-is-not-as-robust-as-it-seems/ It showed that, as of May 2022, 84 percent of job increases relative to pre-pandemic levels in February 2020 were in the public sector, raising questions about the sustainability, fairness, and robustness of Canada’s post-pandemic recovery. (The number has since jumped to 92 percent as of June 2022.)

The article garnered considerable feedback including a thoughtful response from Trevor Tombe, economics professor at the University of Calgary and regular Hub contributor, which was published on these pages last week.The higher educated are benefitting the most from Canada’s economic recovery https://thehub.ca/2022-07-14/trevor-tombe-the-higher-educated-are-benefitting-the-most-from-canadas-economic-recovery/ It’s worth a read if you haven’t already checked it out.

To keep the conversation going about these important labour market developments, we thought it would be helpful to provide further perspective on the public sector’s post-pandemic hiring spree. This broader analysis compares public sector job growth following the pandemic-induced recession of 2020 with the same trendline in the aftermath of the 2008-09 recession sparked by the global financial crisis. It also contextualizes the public sector’s share of total employment in relation to the share that prevailed approximately three decades ago when debt and deficit challenges ultimately led to significant fiscal reforms at the federal level and across several provinces.

The upshot is: post-pandemic public sector employment has grown nearly five times more than it did over a comparable period after the 2008-09 recession, and the public sector’s share of total employment is now at levels not seen since the early 1990s.

Let’s take a look at the data.

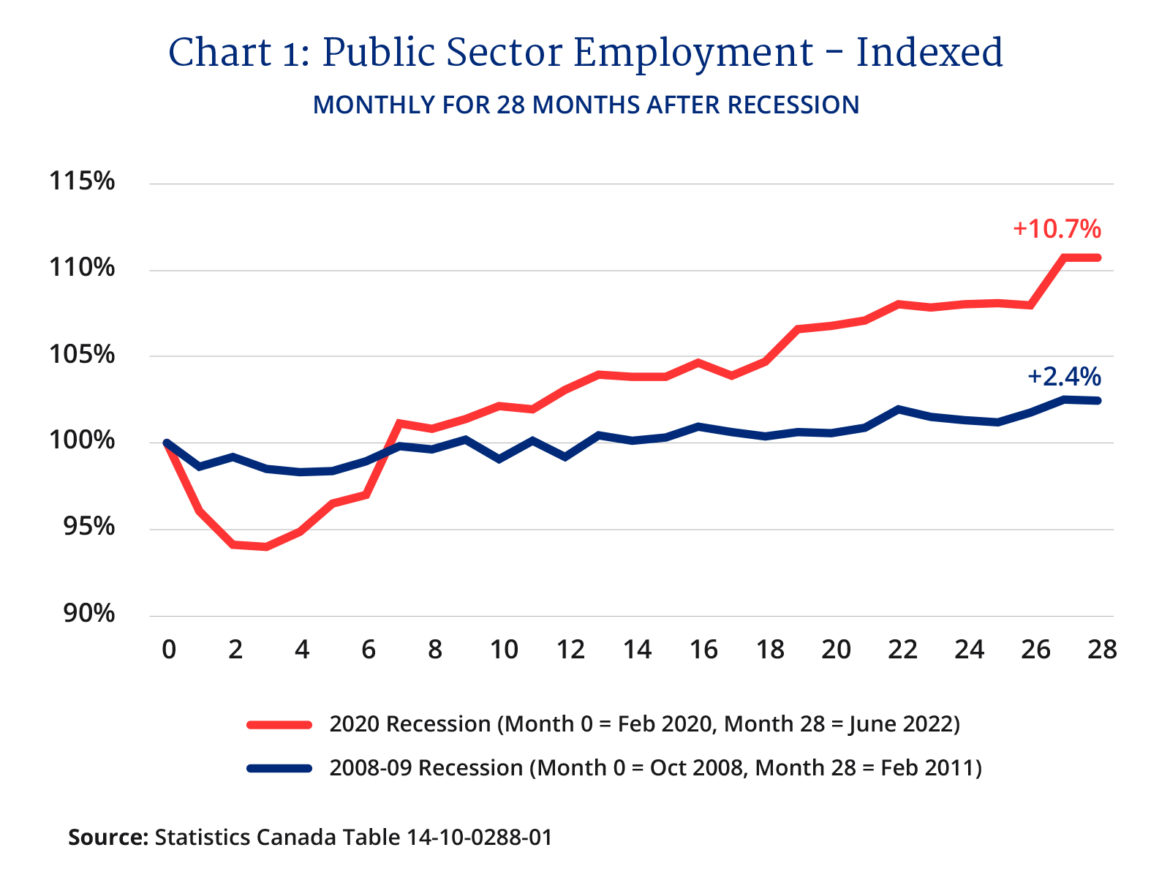

Chart 1 documents the change in public sector employment over a 28-month period for the two recessions: the pandemic-induced recession of 2020 and the financial-induced recession of 2008-09. In both cases, the number of public sector employees in Canada is indexed, where 100 equals the number in the month before employment started to decline. For the 2020 recession, that starting month is February 2020 and for the 2008-09 recession, it’s October 2008.

Of course, no two recessions are the same—the causes, magnitudes, and recoveries always differ—but it’s nonetheless useful to see how the current growth in public sector hiring compares to the growth experienced after the last recession which, notwithstanding its particularities, is still a good reference point for comparison. This analysis helps to contextualize the increase in government employment that we are observing today.

Over the same 28-month period, public sector employment has grown by 10.7 percent following the pandemic-induced recession (February 2020 to June 2022), compared to only 2.4 percent following the financial-induced recession (October 2008 to February 2011).

Put differently, the 28-month growth in government employment after the pandemic-induced recession is nearly five times greater than after the financial-induced recession. Relatively speaking, then, the current spike in public sector hiring is leaps and bounds larger than what occurred after the last recession.

Now, some may argue that the growth in public sector employment that we’re seeing today is justified because the pandemic increased the demand for workers in sectors of the economy such as health care which tend to be dominated by the government in Canada. And, by contrast, there wasn’t a similar demand to grow government payrolls after the financial crisis because most of the short- and long-term challenges it exposed were in the private sector. This may be true to an extent, but it still prompts questions about the magnitude of recent public sector hiring as well as the relative underperformance of private sector employment growth.

Some may also argue that a considerable share of the current growth in public sector jobs is temporary based on the response to the pandemic. Professor Tombe, for instance, estimates that approximately one-third of the 417,800 new public sector jobs from February 2020 to June 2022 are temporary positions. But even if we strip out one-third of the incremental government jobs since February 2020, the increase in permanent public sector employment is still 7.1 percent (or 275,748 jobs) over the 28-month period—or nearly three times the rate of growth after the financial-induced recession.

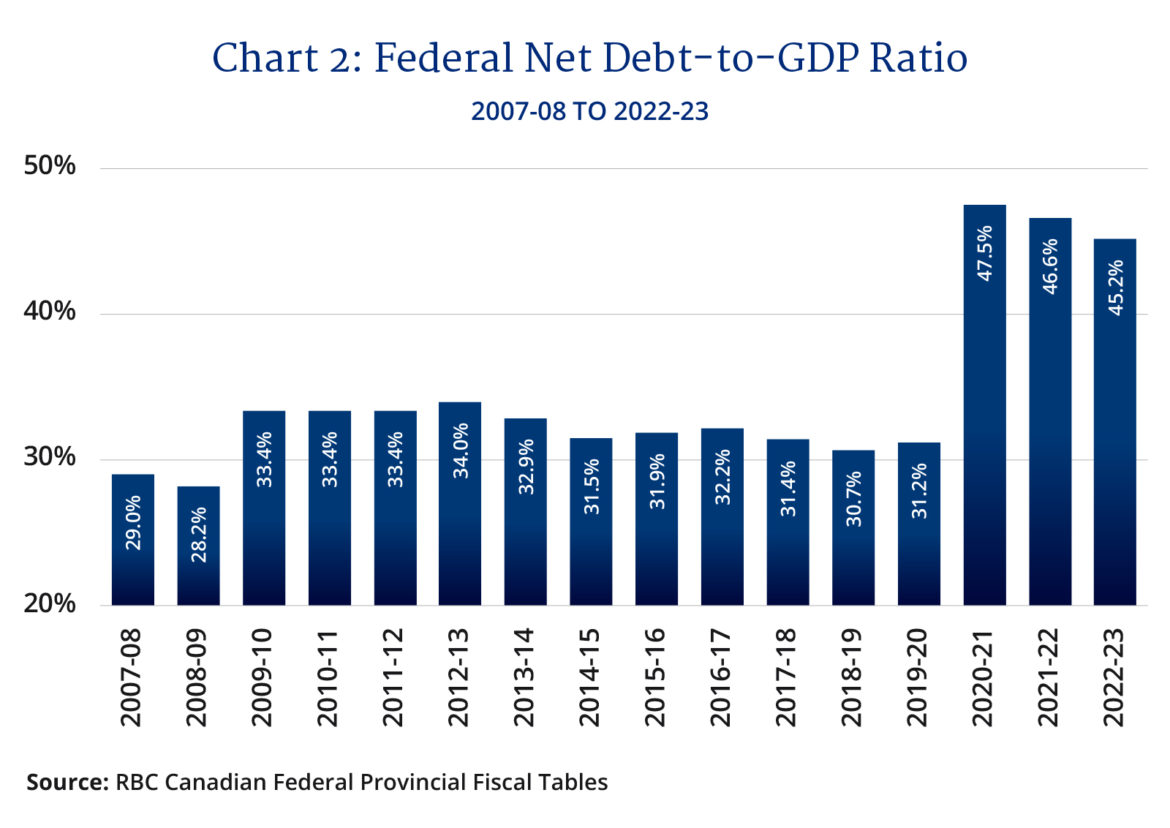

Another key difference between the post-pandemic recovery and the post-financial crisis recovery is the state of public finances across the country. Federal and provincial debt levels are generally much higher today than in the early 2010s, raising questions about Canadian governments’ fiscal capacity to sustain these larger government payrolls.

In fact, for the federal government and all of Canada’s larger provinces (except Quebec), net debt to GDP ratios (which is a common metric to assess fiscal sustainability) in 2022-23 are projected to be much higher than in 2010-11.Canadian Federal and Provincial Fiscal Tables http://www.rbc.com/economics/economic-reports/pdf/canadian-fiscal/prov_fiscal.pdf Consider, for instance, the federal government’s growing debt burden. In 2010-11, the federal net debt to GDP ratio was 33.4 percent. Fast forward to 2022-23 and it’s projected to be 45.2 percent (see Chart 2).

With increased debt levels, it is hard to see how governments will be able to sustainably maintain growing public sector payrolls without changes to their current program spending or tax levels. Rising interest rates will also make managing interest payments on the debt all the more difficult.

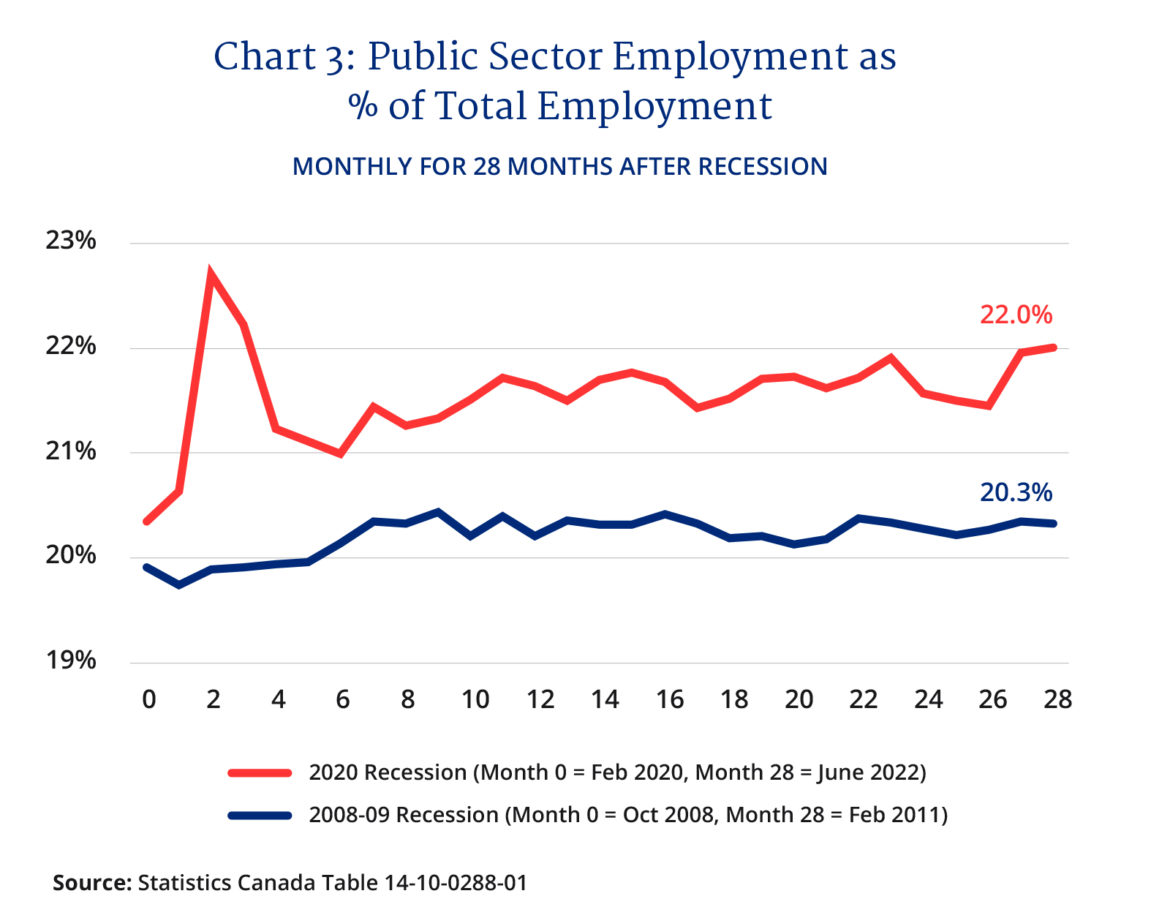

A different proof-point of our government-centric recovery is to compare the current share of public sector employment relative to economy-wide employment with the previous recession and even further back.

Chart 3 displays public sector employment as a share of total employment over the same 28-month period for the two recessions. Notably, over the period of the financial-induced recession, the share of public sector employment was virtually unchanged, rising slightly from 19.9 percent in October 2008 to 20.3 percent in February 2011. By contrast, over the course of the pandemic-induced recession, the share grew from 20.3 percent in February 2020 to 22.0 percent in June 2022 (albeit with a temporary spike in April and May of 2020 when private sector employment collapsed due to economic lockdowns). For perspective, each percentage point of total employment is equivalent to roughly 196,000 jobs.

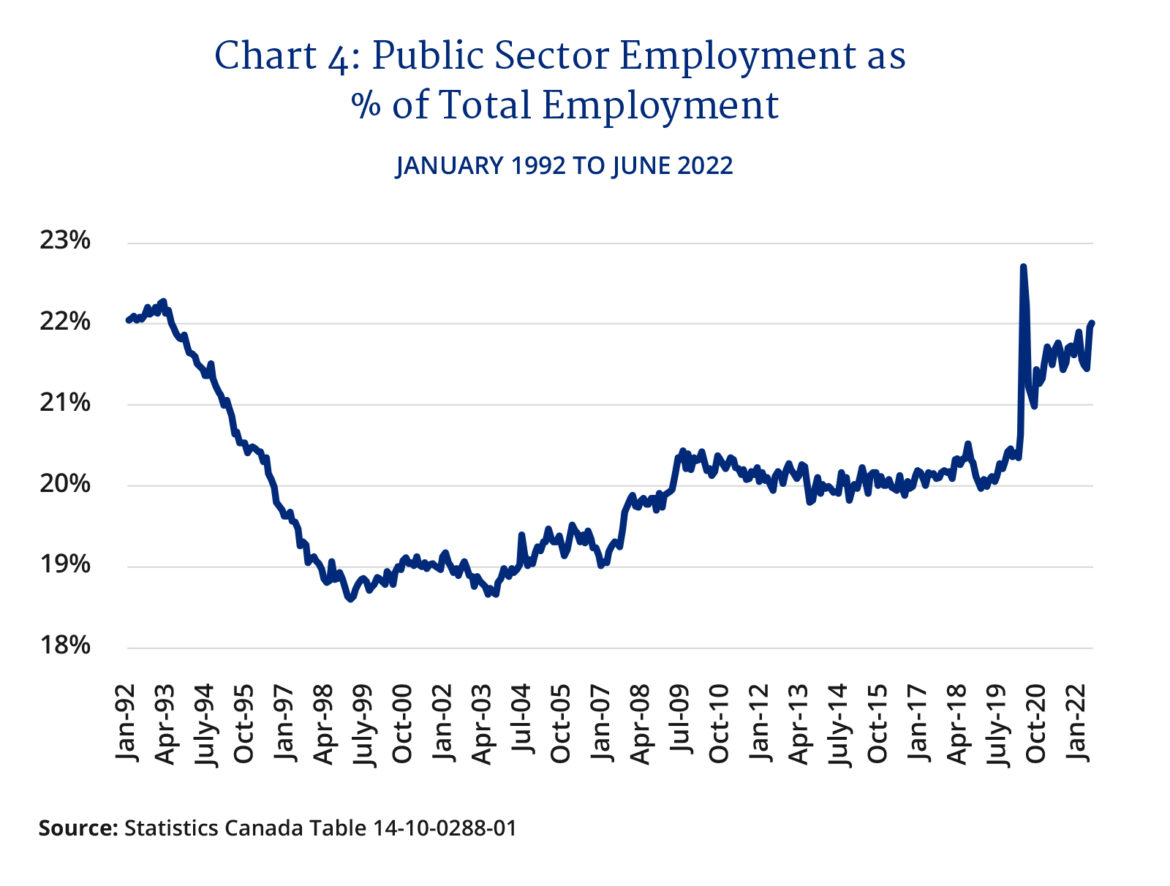

Today, a larger share of Canadian workers is employed in the government sector. In fact, public sector employment now comprises a share of total employment that we have not seen in Canada for nearly three decades—since May 1993, save the two extraordinary months in 2020 (see Chart 4). Put differently, if we exclude the pandemic’s unprecedented circumstances in April and May 2020, the current share of public sector employment is the highest in almost 30 years.

There may or may not be arguments in favour of incremental hiring in different public institutions or occupations. It’s quite likely, for instance, that we’ll need something of an increase in health-care related professions to address pandemic-induced backlogs as well as demographic-driven health-care demands. But the limits here aren’t just scarce fiscal resources.

As the public sector’s share of total employment grows, there’s also a risk of crowding out jobs in the private sector, particularly if comparable talent is scarce. A government-centric recovery can, in other words, stand in the way of a more durable and productive private sector recovery.

If there’s a silver lining in these data, it’s that history shows that governments can scale back their payrolls. As shown in Chart 4, there was a significant rebalancing of public and private sector employment during the 1990s. In particular, the public sector’s share of overall employment in Canada fell due to major public sector reforms enacted by Ottawa and various provincial governments to put their public finances on a more sustainable path.

The size of the federal public service alone was reduced by 45,000 employees—a 14-percent reduction. In today’s context, a similar reduction would merely restore federal employment back to where it was five years before it jumped from 345,833 in 2016-17 to 390,757 in 2021-22.

The key point here is that it happened before so it can happen again. Recent economic and fiscal signs suggest it might have to in the name of a more sustainable, fair, and robust economy.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes

Stephen Staley: Widespread deregulation is Canada’s golden ticket for economic growth