Hub editor-at-large Sean Speer recently challenged Canadian conservatives to “establish something of a generally-acceptable Canadian conservative taxonomy…to understand the points of convergence and divergence across the various conservative factions.”

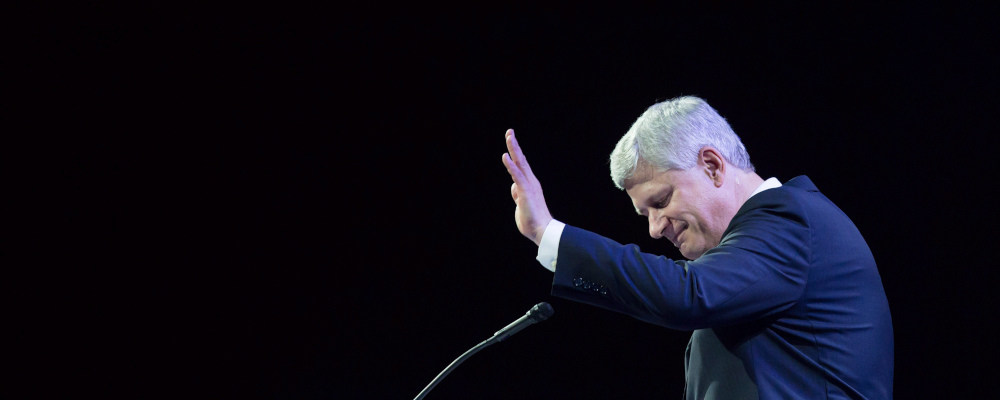

Speer pointed to another essay he wrote with one of us which makes the case for a Canadian ideological conservative taxonomy: a fusion of order in the Burkean sense and liberty in the Hayekian sense. That essay pointed to the development of Stephen Harper’s own ideological and governing conservative taxonomy as a fusion of social conservatism and economic libertarianism.

A more recent Hub essay by Ben Woodfinden makes a compelling case for a “context and circumstance” conservative taxonomy. According to his conception, Canadian conservatism is distinct from the American or German or Dutch kind. Furthermore, it allows for significant shifts in what conservatism means across time, even within the same place. Woodfinden lays out a case for “Tory” conservatism growing out of Canada’s first century-and-a-quarter, fathered in the main by Sir John A. Macdonald, and a more modern “anti-Laurentian” conservatism growing out the last nearly half-century fathered in the main by Preston Manning.

These are both excellent and important. Conservatism must have an ideological foundation—the what and why. And it must have context—the where. And it must have circumstance—the when. But we believe that in order to be complete, conservatism also needs a how. Which brings us to the conservative disposition as a guide to how conservatives should act or govern.

In Theory

We see (at least) three ways of understanding the conservative disposition.

The first is what modern American thinker Yuval Levin means when he writes “conservatism is gratitude.” A less modern expression is Michael Oakeshott’s formulation: “A propensity to use and enjoy what is available, rather than to wish or look for something else; to delight in what is present rather than what was or may be.”

Or to return to Levin: “Conservatives tend to begin from gratitude for what is good and what works in our society and then strive to build on it.” In Canada, this means gratitude not only for faith and family but for our inheritance of a tradition of parliamentary constitutionalism that sustains liberty and has attracted generations of people to make Canada their home.

The second is captured in the words of T.S. Elliot when points to the appreciation of “not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence.” How this comes to be is perhaps best explained by Hayek’s understanding of “spontaneous order” which comes about due to “habits and tradition.” To quote him at a longer length:

We understand each other and get along with each other, are able to act successfully on our plans, because the members of our civilization most of the time conform to unconscious patterns of conduct, show a regularity in their actions which is, not the result of commands or coercion, often not even of any conscious adherence to any rules, but of firmly established habits and traditions… though we do not know their significance and may not even be consciously aware of their existence.

The reliance of “spontaneous order” upon “habits and tradition” is increasingly overlooked today, as we argue below. Together, gratitude and “habits and tradition” point to a third component of the conservative disposition: a keen understanding of the importance of institutions in maintaining order and the suspicion of wholesale changes to those institutions. At an individual level, these institutions include family, faith, and community, separately or together. At the societal level, this includes the set of institutions such as the rule of law, our democratic institutions, and the constitution. At both levels the influence and importance of these things are often and usefully in creative tension. Alexis de Tocqueville lays out this creative tension between “forms,” the legal, political, and constitutional constraints against majority rule, and the democratic will:

Men who live in democratic centuries do not easily understand the utility of forms; they feel an instinctive disdain for them… Since they usually aspire only to easy and present enjoyments, they throw themselves impetuously toward the object of each one of their desires; the least delays lead them to despair…

Forms are more necessary as the sovereign power is more active and more powerful and as individuals become more indolent and more feeble. Thus democratic peoples naturally need forms more than other peoples, and naturally they respect them less. That merits very serious attention.

Tocqueville had in mind the danger of populism to trample individual rights. Courts, juries, constitutions, laws, legal procedures, but also habits or “mores” of liberty and civil deliberation are “forms” that protect us but also sustain effective political action.

In Practice

What do these three traits look like in practice? We would point to Stephen Harper’s incrementalism. In his own words three years before becoming prime minister:

…we must realize that real gains are inevitably incremental… We should never accept the standard of just being ‘better than the Liberals’—people who advocate that standard seldom achieve it—but Conservatives should be satisfied if the agenda is moving in the right direction, even if slowly.

The flip side is, as William F. Buckley was fond of saying, “A conservative is someone who stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” Or at the very least, Slow Down. And this is true whether the underlying changes being proposed are inconsistent with, or consistent with conservative ideology.

One of us has written that a key factor in the downfall of Jason Kenney in Alberta was his too aggressive pursuit of a conservative ideological agenda. In other words, his was not a failure of conservative ideology, but a failure of conservative disposition.

It’s a lesson that conservatives these days seem unwilling to learn.

There is little doubt that both Pierre Poilievre and Danielle Smith, for example, adhere to the conservative ideological canon. Both largely proclaim fealty to smaller government, lower taxes, and market forces over government forces. And while we would both like them both to spend more time showing fealty to stronger families and communities, for the most part, Poilievre and Smith fit within the wide taxonomy of a modern Canadian ideological conservatism. Which is also to say that they both fit very well within the Woodfinden “anti-Laurentian” mold and much less well into the older “Tory” mold that describes some of their leadership opponents.

But what of their conservative dispositions? Poilievre, and to a much greater extent, Smith, rarely express gratitude. Poilievre, and to a much greater extent Smith, design their communications not just to play to but to stoke the anger and resentments of their supporters. Further, and worse, Poilievre, and to a much greater extent Smith, often align with those who would overthrow tradition and/or actively undermine our de Tocqueville “forms.” Their disrespect for “forms” is based upon the belief in a deep crisis in Canadian politics and constitutional order. Like the Liberals who panicked and unnecessarily invoked the Emergency Act last February, they are willing to play fast and loose with Canada’s “forms” as a way of addressing a crisis.

Poilievre, for example, has openly aligned himself with the Canadian trucker convoy movement. Let’s for the moment take him at his word that he rejects the blatantly unconstitutional goals and means of the leadership of that movement. Let’s just focus on one of the most prominent slogans and symbols of the movement, the omnipresent “F-ck Trudeau” flags, bumper stickers, and t-shirts. Never has there been a more indolent and more feeble expression of disdain.

This indolent and feeble expression is, to make things worse, politically impotent, which is another way to say it is an empty expression of rage populism. While flying them undoubtedly reflects an underlying and legitimate concern with government overreach and abuse of power, doing so is just political theatre that makes the waver feel good. No amount of waving obscenity-laced flags will change the government, and no leader standing by those waving flags will convince swing voters to swing their vote to the Conservative side.

We take no back seat to anyone in desiring a Conservative replacement of the current Liberal government. However, we recognize that they are the legitimately elected government of Canada according to the democratic forms we have established. Those flags (not to mention the outrageous views of the convoy leaders) are an unconservative expression suggesting otherwise.

Much worse is Danielle Smith, who has tied her leadership fortunes to a Sovereignty Act. One of the coauthors of that Act is co-chairing her campaign and another has described the Act using the following words: “But, but — gasp! — that would be unconstitutional! Indeed, that is the whole point.”

OK. Let’s play along. Has no one in the Smith camp thought through what a federal response might be to an unconstitutional law passed by Alberta? The authors of the Sovereignty Act say the next step is a referendum on separation—a radical fringe idea with no discernible support in Alberta. Or to come at it another way, an idea that is risible to enough Albertans to all but guarantee an NDP majority. One wonders if it’s not just more populist political theatre.

On the other hand, if they are serious, the Sovereignty Act, in one fell swoop (that is to say, anything but incrementally) upends and violates the constitutional norms on which our country functions. Smith says she is just doing what Quebec is doing, but you will search in vain for the equivalent piece of legislation passed in that province. There is no evidence that Smith will make any effort to get other provinces onside, including Quebec—which can also be Alberta’s ally in protecting provincial constitutional powers. Sure Quebec legitimately uses the notwithstanding clause for defensible and indefensible reasons, but the proposed Sovereignty Act is a notwithstanding clause on steroids. It is an insurrection by (il)legal means.

This is not conservative. It is the very opposite—it is radical.

If those were the only examples, Smith, and to a greater extent Poilievre, could perhaps be forgiven for engaging in the typical over-excitement of a leadership campaign. But to them, we can add impetuous support for Bitcoin and a disregard for the federal institutions like the Bank of Canada, in the case of Poilievre. Open disdain for pandemic vaccines, support for Ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine, and categorical rejection of restrictions for any reason in the case of Smith. And playing footsie with silly conspiracy theories (and theorists) around the World Economic Forum for both.

In Conclusion

Any conservative taxonomy must, in addition to including ideology, context, and circumstance, take a measure of conservative disposition. And we should use all of these to measure prospective conservative leaders.

We would urge our fellow conservatives to put a greater emphasis than in the past on a conservative disposition. To take a measure not just of conservative ideology, geography, or relevance, but to take a measure of something greater, namely character.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes