Past pandemics—from the Black Death to the Spanish Flu—have always brought about large social and economic changes. The COVID-19 pandemic has also brought many changes, not least of which was the large-scale implementation of working from home in many sectors of the economy. This came about at the behest of many employers in response to public health measures to help control the spread of the virus. However, with COVID-19 in abeyance, there are increasing calls for workers to return to the office.

Unlike past pandemics when economic production was more goods intensive, modern economies are dominated by services. Increasing digitization of the workplace and business operations allowed for many service-type activities to be done remotely via teleworking and appears to have been happily embraced by many workers who have enjoyed the flexibility as well as the reduction in commuting time and other costs. Indeed, one American study found annual commuter congestion costs and travel delays in 2020 were half of those in 2019 and per-commuter costs in 2020 dollars had fallen to 1982 levels.2021 Urban Mobility Report. Texas A&M Transportation Institute. https://static.tti.tamu.edu/tti.tamu.edu/documents/mobility-report-2021.pdf One imagines that the decline in commuting and the drop in associated emissions also contributed to better air quality in many cities as well as reduced traffic congestion.

An early analysis suggested that hybrid models of remote work were likely to persist after the pandemic, especially for highly educated workers in knowledge economy-intensive occupations that required computer interaction, thinking creatively, processing and analyzing data, as well as information, administrative, and organizational activities.Lund, Susan, Anu Madgavkar, James Manyika and Sven Smit (2020) What’s next for remote work: An analysis of 2,000 tasks, 800 jobs, and nine countries. McKinsey Global Institute. November. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/whats-next-for-remote-work-an-analysis-of-2000-tasks-800-jobs-and-nine-countries Accessed March 26th, 2022 Indeed, a study by Statistics Canada (see figure 1) found that the proportion of jobs that could be performed from home was sector dependent, ranging from less than 15 percent in construction and agriculture and 20 percent in manufacturing to as much as 85 percent in finance and insurance, educational services, and professional, scientific and technical services.Deng, Z., R. Morissette and D. Messacar. 2020. Running the economy remotely: Potential for working from home during and after COVID-19. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

However, the shift of employment to home activity is a feature that is now being subjected to review despite a demonstrated preference by many workers to continue remotely in a wide range of sectors. Indeed, the continuation of remote work has slowed the revival of downtown cores and associated businesses, much to the chagrin of some urban mayors with substantial downtowns. For example, the Mayor of Ottawa has exhorted the federal government to bring reluctant home civil service workers back workers downtown to bolster local businesses. This is probably particularly galling for cities with a high proportion of civil servants like Ottawa given that since 2016, the federal government has been engaged in a veritable civil service hiring spree that has expanded the core civil service by nearly one-third since 2015.

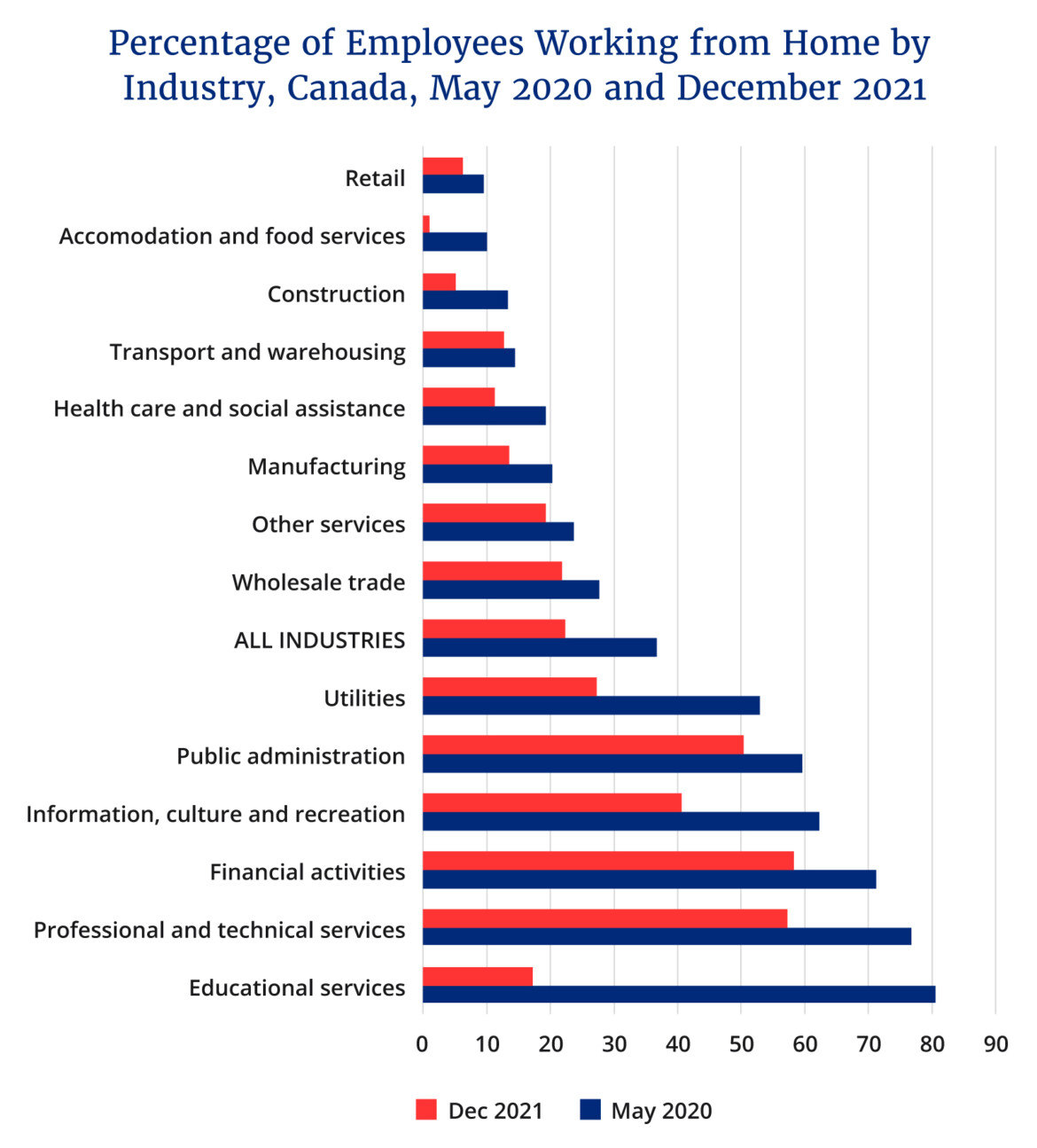

According to a recent Statistics Canada report, in May of 2020, about 37 percent of the Canadian workforce was working from home, while in the United States the proportion was comparable at 35 percent. As COVID-19 restrictions began to be relaxed, there was a decline in work-from-home rates and by December of 2021 they had fallen to 22 percent in Canada but 11 percent in the United States. This was due mainly to a greater transition in the United States to less restrictive COVID measures relative to Canada, based on the University of Oxford’s COVID-19 Government Response Tracker.S. Clarke and V. Hardy (2022) Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: How rates in Canada and the United States compare. Statistics Canada. Economic and Social Reports. Catalogue no. 36-28-0001. The rate of return-to-office resumption also differs across sectors.

If one compares the percentage point decline in working from home across sectors and ranks them, some sectors have seen larger resumptions in return to the office than others. Education has experienced the largest return going from 81 percent working at home to 17 percent. Professional and technical activities, financial services, and public administration as of December 2021 were all still above 50 percent in terms of employees working from home. In the end, it has been estimated that about 40 percent of jobs in Canada can be performed remotely,G. Gallacher and I. Hossain (2020) Remote Work and employment Dynamics under COVID-19: Evidence from Canada, Canadian Public Policy, July, S44-S54 suggesting that having over 50 percent of your employees working remotely in some sectors may be a bit on the high side.

The dimensions of the working-from-home experience are quite interesting and may have implications for any transition back to the workplace. Women had higher rates of working from home than men—43 percent of Canadian female employees worked from home while 31 percent of male employees did so. Some of this was the result of women being concentrated in industries where working from home was easier to do, as well as the reality that women tended to have a larger role both in homeschooling and childcare as the pandemic sent children home from schools.

In terms of other demographics, it appears that full-time employees were more likely to work from home than part-time, and those with post-secondary degrees were also more likely to work from home. Indeed it has been found that poorer workers, male workers, workers without a college degree, private sector workers, single workers, small firm workers, seasonal or contractual workers, part-time workers, younger workers, and non-immigrant workers tend to be employed in jobs for which remote work was less possible.G. Gallacher and I. Hossain (2020) Remote Work and employment Dynamics under COVID-19: Evidence from Canada, Canadian Public Policy, July, S44-S54

Going forward, it is likely that there will continue to be a degree of working from home given the worker preferences for it that were formed during the pandemic. At least one early study found that 80 percent of individuals who worked at home during the peak of the pandemic would like to work at least half their hours at home going forward.T. Mehdi and R. Morrisette (2021) Working from home after the COVID-19 pandemic: An estimate of worker preferences. Economic and social reports, Statistics Canada, 36-28-0001 However, accommodating such desires ultimately requires a dual coincidence of wants and needs between employers and employees, and bottom-line considerations will inevitably come into play.

One study on IT professionals working from home during the pandemic found that for IT workers, hours worked increased but average output per hour worked productivity declined slightly causing productivity to decline between 8 and 19 percent.M. Gibbs, F. Mengel, and C. Siemroth. BFI Working Paper, Jul 13, 2021, Work from Home & Productivity: Evidence from Personnel & Analytics Data on IT Professionals. https://bfi.uchicago.edu/working-paper/2021-56/ However, it turns out that much of the increase in working hours was due to more and longer online meetings. Other studies have found productivity increased, but again it depends on the sector.

In the end, it is likely that a substantial amount of remote work will persist moving forward though the degree will depend on the benefits and costs of such arrangements for the firms and sectors involved as well as the preferences of the affected workers. Many firms which can conduct much of their work remotely can enjoy important cost savings when it comes to office space. However, there is also the important issue of the need for social interaction, particularly in sectors such as education and health. All business in the end has a personal component that can suffer in the absence of person-to-person contact.

At the same time, governments during the pandemic have grown accustomed to more direction and intrusion in economic life and ultimately may have their own reasons for encouraging more remote work. After all, fewer people commuting means one can postpone a lot of urban infrastructure renewal, thereby redirecting spending to other things. As well, there may be environmental benefits to continuing remote work arrangements via reduced emissions, though remote work may also have mixed environmental benefits. While there may be reduced emissions from commuting and transportation, along with improved air quality, there can be higher energy consumption while working from home.

In the end, to work remotely or not work remotely will be a question with no one size fits all answer.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Mark Carney’s first major tests

The Weekly Wrap: Trudeau left Canada in terrible fiscal shape—and now Carney’s on clean-up duty

‘Another round of trying to pull capital from Canada’: The Roundtable on Trump’s latest tariff salvo

Canada is losing ground on investment. Here’s where