As we try to understand the restive state of our economy and politics, the role of income inequality and the accompanying wealth gap in Western societies remains the source of considerable debate.

Progressives contend that unequal outcomes are harming social mobility, weakening social cohesion, and contributing to the overall state of political dysfunction. Conservatives, by contrast, point to different arguments including that inequality has stabilized, or that it reflects life-cycle trends, or that it doesn’t really matter anyway.

I’ve made versions of the latter arguments over the years. My main case has been that unequal outcomes generally aren’t a problem to be solved in a market economy and instead the goal of public policy should be to extend opportunity as broadly as possible. Policymaking attention should, in other words, be paid to fostering greater social mobility rather than trying to equalize outcomes through higher levels of redistribution.

What if, however, both sides are somewhat right? Or, to be more precise, the truth is somewhere in the middle—namely, the middle of the labour market’s skills distribution. Let me try to explain.

The chief problem with the Left’s inequality analysis is that it has misread causes. Its arguments tend to imply something corrupt, greedy, or systemic about the unequal outcomes in our society. This is how in large part we’ve ended up with the language of “privilege” permeating modern political discourse. It ceases to be about a question of policy trade-offs and becomes a moralistic enterprise to overturn generations of social arrangements including, in some cases, the market economy itself.

The whole “tax-the-rich” movement therefore often seems to view higher taxes as an end in itself. Talk of “taxing billionaires out of existence” from leading progressives like Thomas Piketty is a bit of a tell. The case for confiscatory taxes is often implicitly presented as a means to equalize downward rather than as part of an overall plan to boost low-income individuals or households upwards.

Notwithstanding the inherent flaws in these arguments, it would be a mistake to underestimate their political salience. Polling tells us that Canadians, Americans, and other Western populations broadly support higher taxes on high-income earners.

This has manifested in growing political action. In Canada, for instance, we’ve seen a steady set of redistributive tax reforms at the federal and provincial levels, including new and higher tax rates on high-income earners, a redistributive carbon tax and cash transfer, and new taxes on capital and now luxury goods.

Yet while the Left has been wrong in how it has come to think about the causes and in turn proper responses to income inequality, I’ve come to understand in recent years that its basic insight isn’t completely incorrect. Structural changes in our labour market—namely, the relative decline in mid-skilled jobs—are far more responsible for income inequality than any nefarious actors. The decline in manufacturing employment in particular is a major factor in understanding what’s come to be called an “hourglass economy.”

The basic idea here is that the old goods-producing economy produced a more egalitarian labour market in which most jobs were clustered in and around the middle of the skills distribution. Today’s service-based economy, by contrast, is far more bifurcated into low-paid and often low-skilled jobs in care work or personal services and high-paid and often high-skilled jobs in professional, administrative, and financial services. This labour market development is often described as “job polarization.”

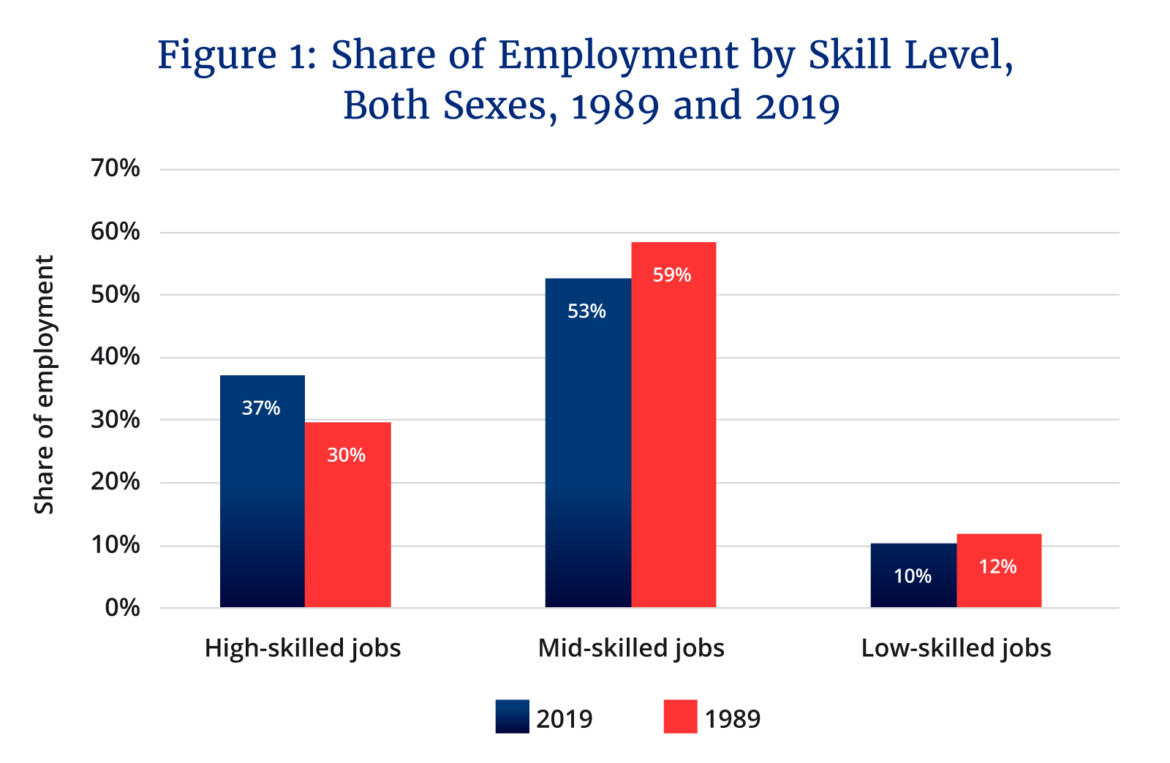

It’s been occurring across Western economies for the past 30 years or so. Canada is no exception. Between 1989 and 2019, the Canadian economy experienced a 6-percentage point decline in the relative share of mid-skilled jobs (see Figure 1). That number jumped to 7.5-percentage points in Ontario and Quebec where there was a high concentration of manufacturing employment that had historically been a significant source of middle-class opportunity.

These labour market developments have major political economy implications including for the broader debate about income inequality. As the relative share of mid-skilled jobs falls, many are able to climb up the skills distribution into higher-skilled opportunities, but some invariably fall downwards into lower-skilled employment. The income consequences can be significant: those in high-skilled jobs earn almost four times more than those working in low-skilled jobs. The upshot is that we’ve ended up with a more bifurcated labour market in which unequal outcomes may be increasingly hard-wired into its structure.

A key exception to these trends over the past two decades has been natural resource employment. Research in fact shows that Canada’s job polarization has been less marked than peer jurisdictions because natural resource sectors in general and the oil and gas sector in particular have had significant labour demand for mid-skilled workers and therefore represented an “employment alternative to low-paying service jobs.”

This point cannot be overemphasized: as the labour market has gone through a process of polarization in the twenty-first century, natural resource employment has generally counteracted this trend and in so doing fortified Canada’s middle class. As University of British Columbia economist Kevin Milligan has put it: “The resource sector has contributed substantially to the good jobs that underpin middle-class resilience.”

There are two main policy takeaways from this analysis. The first is that it should challenge the simplistic view that income inequality is caused by unjust economic forces and therefore the best policy response is greater redistribution in the tax-and-transfer system. This dominant yet wrong interpretation focuses too much on the symptoms of inequality rather than aiming to properly understand and address the underlying cause of an increasingly bifurcated labour market in which unequal outcomes are something of a natural outgrowth.

The best means for addressing income inequality in the modern labour market is to create a new generation of middle-class opportunities in order to replace the ones that have disappeared in recent decades due to a combination of technology and trade. In simplified terms, this amounts to a “good jobs” agenda dedicated to transforming today’s low-skilled jobs into tomorrow’s mid-skilled occupations by pulling low-skilled workers up the skills ladder through education, training, and productivity-enhancing investments. The key point here is that a new generation of good jobs will ultimately derive from a mix of public and private investments in human and technological capital rather than state-led redistribution.

The second takeaway is that policymakers should be more cognizant of the anti-inequality role played by resource-based employment in Canada’s labour market. This of course doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t pursue ambitious climate policies including possibly imposing high emissions standards on resource-based companies. But it does mean that we ought to be more cognizant of the employment effects of climate policy and the extent to which it may lead to greater job polarization and in turn contribute to more inequality.

This reckoning seems particularly important for progressives who often demand both more stringent climate policies and greater action on inequality. As Milligan has argued: “For Canadians concerned with inequality, the equalizing effect of resource development on our economy is too strong to ignore.”

The main point though is that understanding the current state of inequality through the lens of job polarization should shift the focus of our policy debates from taxing the rich to creating the next generation of good, middle-class jobs. That would be a healthy development for our economy and politics.

Recommended for You

The Weekly Wrap: It’s time to cut through Chesterton’s Fence and implement sweeping reform in Canada

Has the Left lost its masculine energy?

The Week in Polling: Young Canadians delay milestones due to high costs, Liberals lose the youth vote, and most Canadians fear a Trump-Vance White House

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie