Housing is near the top of the political agenda these days and for good reason. Housing affordability has reached what some have described as a “crisis.” Consider, for instance, that home prices increased by roughly 30 percent over the pandemic. Even expectations of falling housing price in recent weeks anticipate that they’ll only return to pre-pandemic levels.

This has led to a growing political consensus that a key solution to Canada’s housing woes is more housing supply. Scotiabank analysis has shown that the country’s housing stock is, on a population-adjusted basis, the lowest in the G-7. Boosting housing supply is therefore an imperative.

Yet that is easier said than done. It requires that provincial and local policymakers create the conditions for faster and more affordable housing construction. That’s a far cry from the current investment and construction environment.

Residential housing developers currently face a perfect storm of supply chain constraints and fundamental issues (like rising interest rates and high construction costs) that stand in the way of contributing to more housing supply. These unprecedented conditions make it nearly impossible to build.

The cries of the developer’s shrinking profit margin have been heard before, but in good economic times, they were ignored. Today, government should listen.

There are a few telling signs that this present predicament is unique: rental projects have converted to condominiums because the margin to build rental has been eradicated, developers are delaying sales launches, and some are outright canceling their projects.

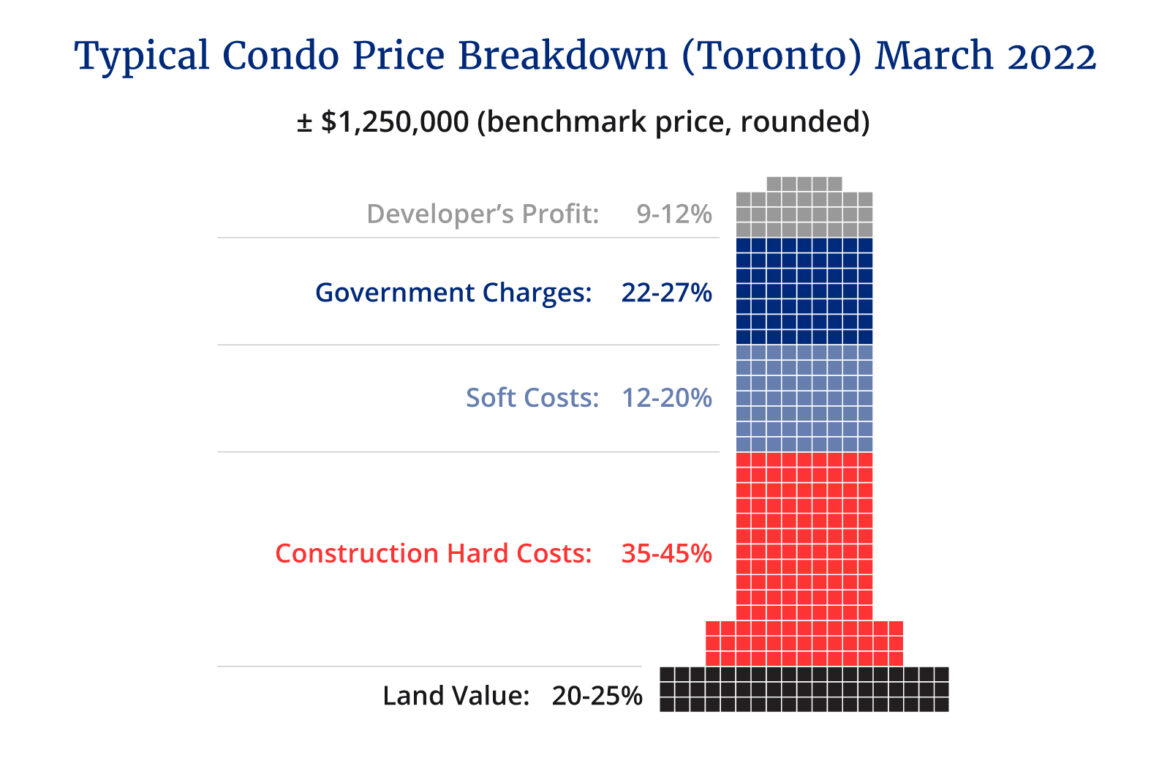

Marlon Bray from Altus Consulting recently shared a post that perfectly, and all too simply summarizes the cost to build a residential condominium project in Toronto, Canada’s largest urban city. Just consider:

To break down the visual: “Construction Hard Costs” are the materials to build your building; “Soft Costs” are all consultant costs related to the building (like the planners, lawyers, sales, and marketing teams); and “Government Charges” include all municipal taxes and related policy fees.

This year, global issues affecting supply chains, coupled with labour strikes, have increased “Construction Hard Costs.”

“Soft Costs” have increased as a result of wage hikes and employment shortages and, most importantly, the City of Toronto has proposed increases to nearly all “Government Charges” (namely “Development Charges” and “Parkland Costs”).

Toronto’s housing industry has had a good couple of years—not just developers have profited, but so has the City.

The City government has taken advantage of strong market demand and the subsequent “condo boom” to introduce policies and guidelines to address critical socio-economic problems like affordable housing and climate change. Developers adopted these policies and adhered to these guidelines because ultimately any increase in government regulatory costs could be offset by a developer’s own increase to the purchaser sale price.

In turn, this worked out in the City’s favour: municipal politicians were able to deliver on campaign promises (Support Climate Change!) and increase their revenues without raising the property taxes of their existing voter base. The future cost were borne instead by the first-time homebuyer of a condo development.

But the times have changed, and we are only now realizing the full effects of the impact of COVID-19 and the Russian war on Ukraine. Europe is bracing for a winter without Russian gas, as well as other world issues that are affecting global supply chains. Inflation is driving up the costs of goods and interest rates are climbing too. Everything is more expensive and it is tough to get goods and secure much-needed labour.

Quite simply, when costs go up, buildings do not.

The risk here is that the future supply of homes that we need so desperately is not going to get built, and the homes that do will come at a great cost.

Housing developers are in a for-profit business—many with a fiduciary responsibility to investors and, of course, their lenders. When costs go up and that 10 percent profit margin starts to shrink, business in Toronto no longer looks so good.

Municipalities can control the costs they impose on housing. If other municipalities outside of Toronto have lower or more competitive fees, developers will seek out those opportunities to build in other jurisdictions.

These regulatory costs are geographic. If Toronto is intent on raising its fees, cranes will move to other areas. More condos will be built on transit lines and not in the core of downtown Toronto, taking away people, tax revenue, and life from the province’s capital.

If governments are going to continue to lean on private developers to support their campaign promise of more homes, then the industry will require better investment and construction conditions.

In the immediate term, there is a role for the provincial government to reduce government costs by decreasing, pausing, or altogether eliminating development charges for affordable or inclusionary zoning housing units and purpose-built rental units. It makes little sense to subsidize the sale price of a unit and tax the construction. This is the housing equivalent of charging for parking at a food bank.

Other options include capping annual interest rate increases for development charges and capping and standardizing parkland dedication charges.

Projects are getting canceled and delayed today, and without reforms to the line items that we can control—like government charges—the more homes that were promised will not get built. On the precipice of municipal elections and much whispered housing legislation from the province, these are the necessary steps.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Five Tweets on Western Canada’s devastating wildfires

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats