Canadian health-care spending is starting to come down to earth after ballooning during the pandemic, but governments are still grappling with the cost of Canadians catching up on deferred care from the last two years.

Total health spending in Canada is expected to reach $331 billion in 2022, or $8,563 per Canadian following the COVID-driven surge of spending since 2020.

In 2020, federal, provincial, and territorial governments (combined) spent $770 per person on health-specific funding to deal with COVID-19. Meanwhile, this pandemic response funding is projected to decline to $376 per person in 2022.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information’s release this morning of the National Health Expenditure Trends 2022 provides insight into Canadian health spending during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Total health expenditure in 2022 is expected to rise by 0.8 percent, following growth of 13.2 percent in 2020 and 7.6 percent in 2021 while in the four years prior, growth in total health spending averaged 4 percent annually. In 2020, total health spending in Canada was $305.1 billion with per capita spending at $8,021. In 2021, forecasted health expenditure growth moderated bringing total health spending and per capita to an estimated $328.4 billion and $8,586.8 respectively.

In terms of spending relative to the size of the economy, it is anticipated that total health expenditure will decline to 12.2 percent of Canada’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2022, following a high of 13.8 percent reached in 2020 but still well above the pre-pandemic 11 percent.

According to the CIHI, health spending in 2022 is being driven by care that was deferred during the pandemic, resulting in an increase in the number of health care services provided compared with pre-pandemic years. In addition, demographic factors such as population aging and population growth will continue to contribute to spending growth as will the effects of wage and cost inflation. Nevertheless, growth is still expected to moderate in 2022, and indeed once adjusted for inflation and Canada’s robust population growth it would appear that real per capita total health spending is projected to actually decline in 2022 coming in at -1.8 percent compared to 4.3 percent in 2021 and 7.7 percent in 2020.

Health-care spending in Canada seems to be marked by a case of simultaneous feast and famine. It is interesting that stories about health sector resource shortages dominate the pandemic’s wake and yet according to the CIHI, in 2020, of the 38 OECD countries, Canada’s total health expenditure to GDP ratio was the second highest and exceeded by only the United States. In per capita spending during 2020, Canada ranked somewhat lower coming in seventh place behind the United States, Switzerland, Germany, Norway, The Netherlands, and Austria but ahead of everyone else. Oddly enough, much is made of Canada’s aging population, but Italy and Japan have much higher shares of seniors in their population, but both spend less on health than Canada in terms of either the GDP share or per capita. And despite our vaunted commitment to public health care, we have a lower publicly funded share of health spending than the OECD average.

We are entering a turbulent period in Canadian health-care spending and provision. While there have been surges in health-care spending that have raised total spending to new heights, it would nonetheless appear that in the new inflationary environment accompanied by robust population growth, health spending resources per person are actually expected to decline in 2022. And like all things Canadian, there can be expected to be regional variations in the impact based on factors such as economic growth, government revenue growth, and demographics resulting in variations in not only total health spending but in the approximately two-thirds that is provincial government health spending. However, the differences are already substantial.

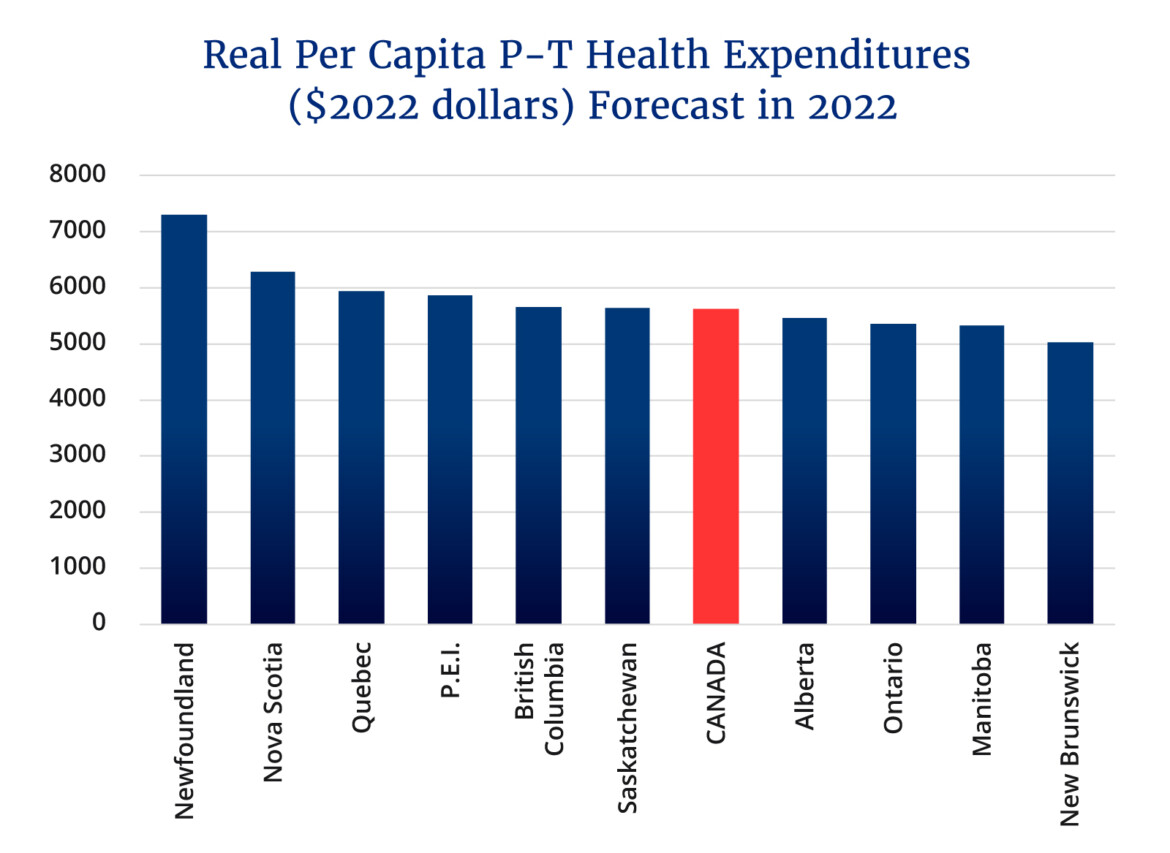

Figure 1 presents real per capita provincial government health spending (in $2022) using the CIHI data estimates provided for 2022 and they show that the average for Canada was $5,619 with six provinces above the average and four below. Spending ranges substantially from a high of $7,295 for Newfoundland and Labrador to a low of $5,028 for New Brunswick—a nearly $2,300 difference from top to bottom.

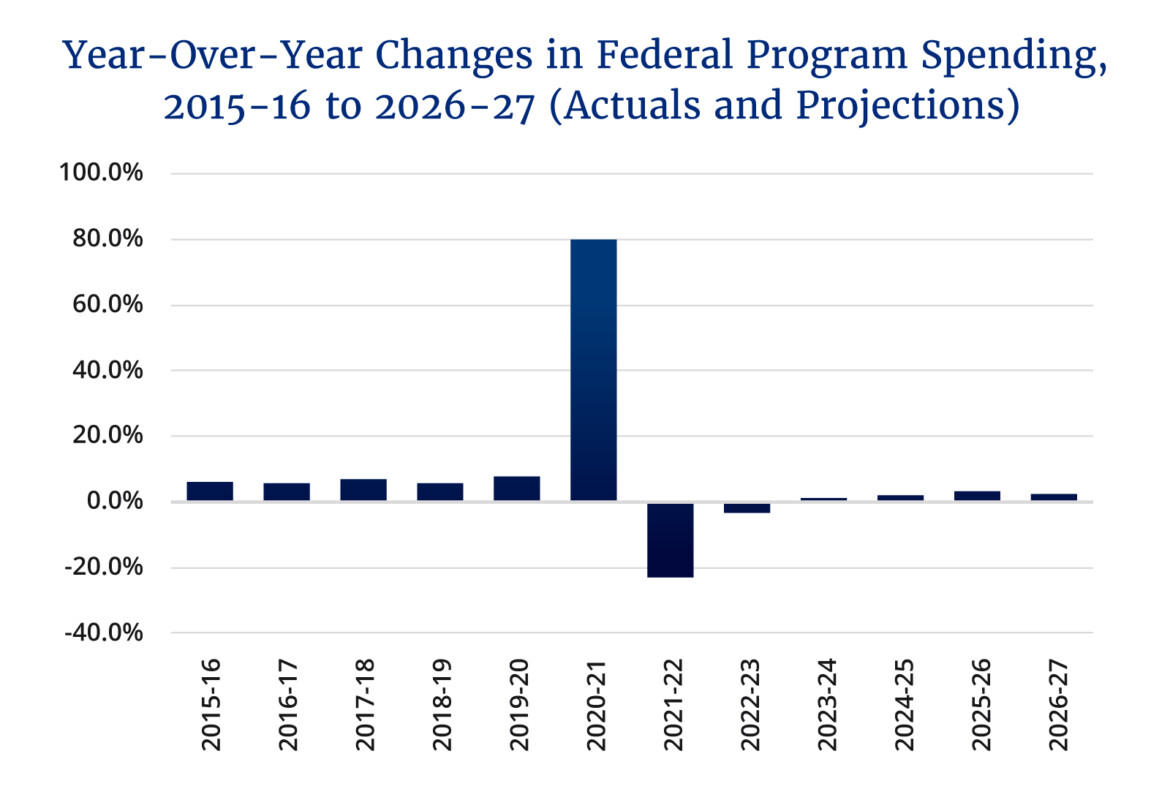

Figure 2

Figure 2 plots real per capita spending for the provinces over time with some regional aggregation of provinces to outline trends more clearly and they show that while provincial health spending moves together, the range between high and low-spending regions increased during the 1980s, fell during the spending declines of the early 1990s that were marked by severe recession and the federal fiscal crisis, and then grew again as funding expanded after 2000.

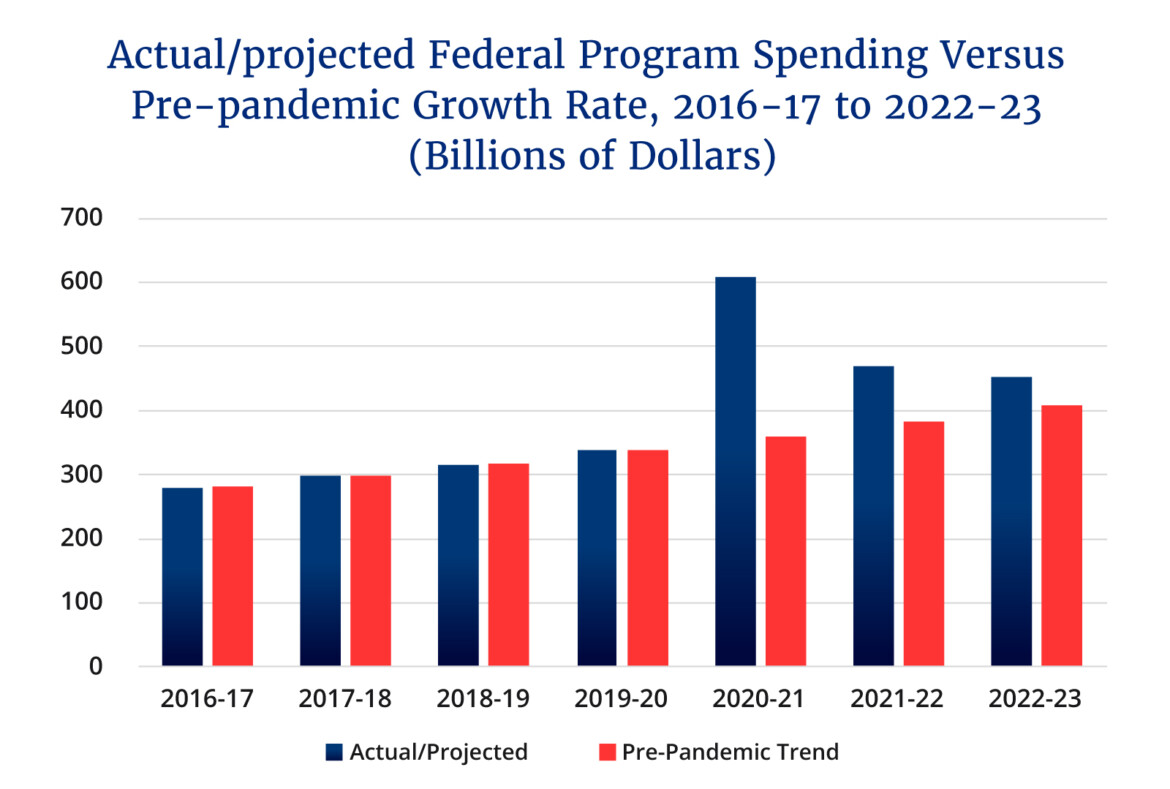

Figure 3

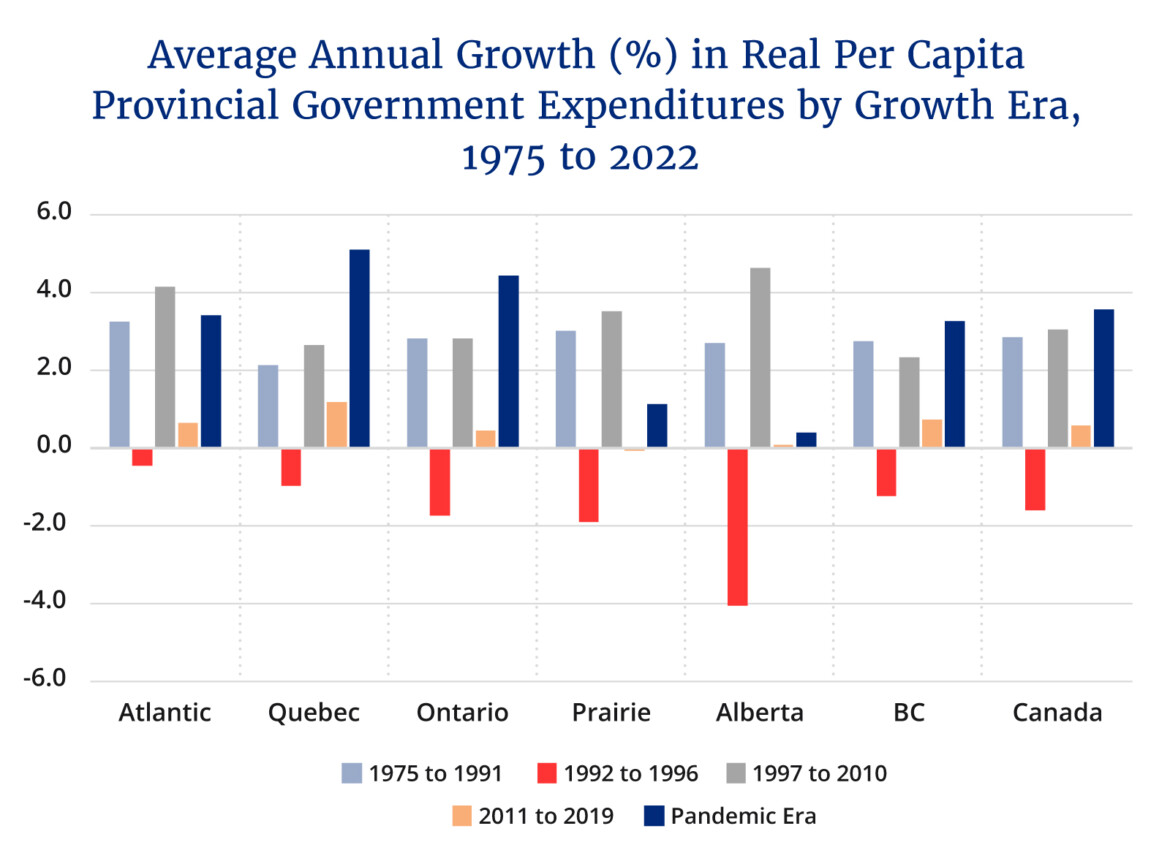

The pandemic era notwithstanding, real per capita health spending has grown since 1975 but there have been distinct phases of growth as illustrated in figure 3. For Canada as a whole, the period 1975 to 1991 saw real per capita spending growth average 2.8 percent annually but this was followed by the retrenchment of the 1992 to 1996 period which saw average annual growth decline an average of 1.6 percent annually. The period from 1997 to 2010 was an era of robust economic growth and marked by the enrichment of federal health transfers with the start of the 6 percent escalator of the 2004 Health Accord. As a result, annual growth rates during this period averaged 3 percent in Canada with Alberta and the Atlantic provinces followed by the Prairies seeing particularly pronounced growth.

While the six percent growth transfer escalator continued until 2017, advance notice that it would end was provided circa 2011 and combined with the effects of the 2008-09 Great Recession and robust population growth, seems to have encouraged provincial governments to rein in their real per capita health spending growth during the 2011 to 2019 period.

After years of concern that health spending was unsustainable, the cost curve appears to have finally been bent. Canada as a whole saw real per capita provincial government health spending average annual growth of 0.6 percent with only Quebec growing above 1 percent annually. However, the three years of the pandemic saw growth rates soar and the question remains as to what will happen next.

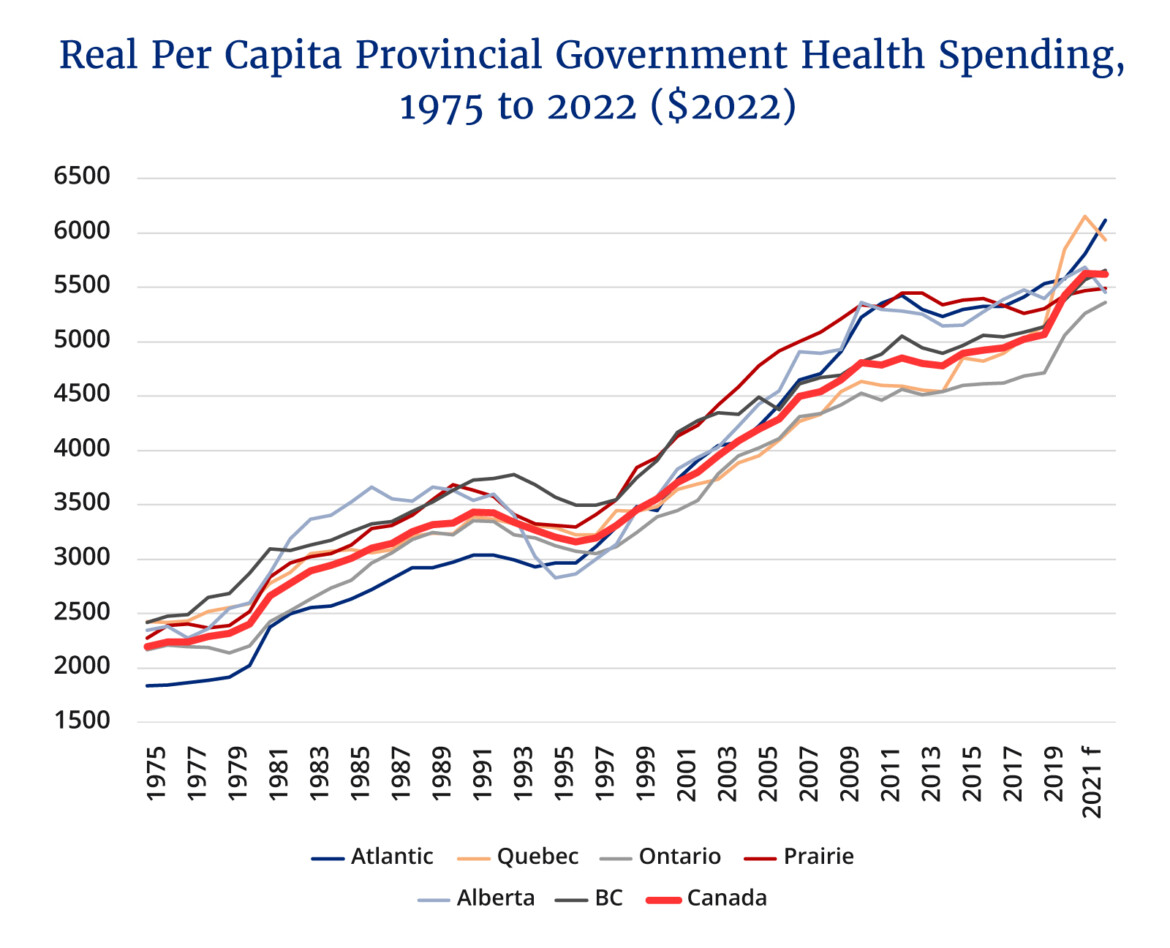

Figure 4

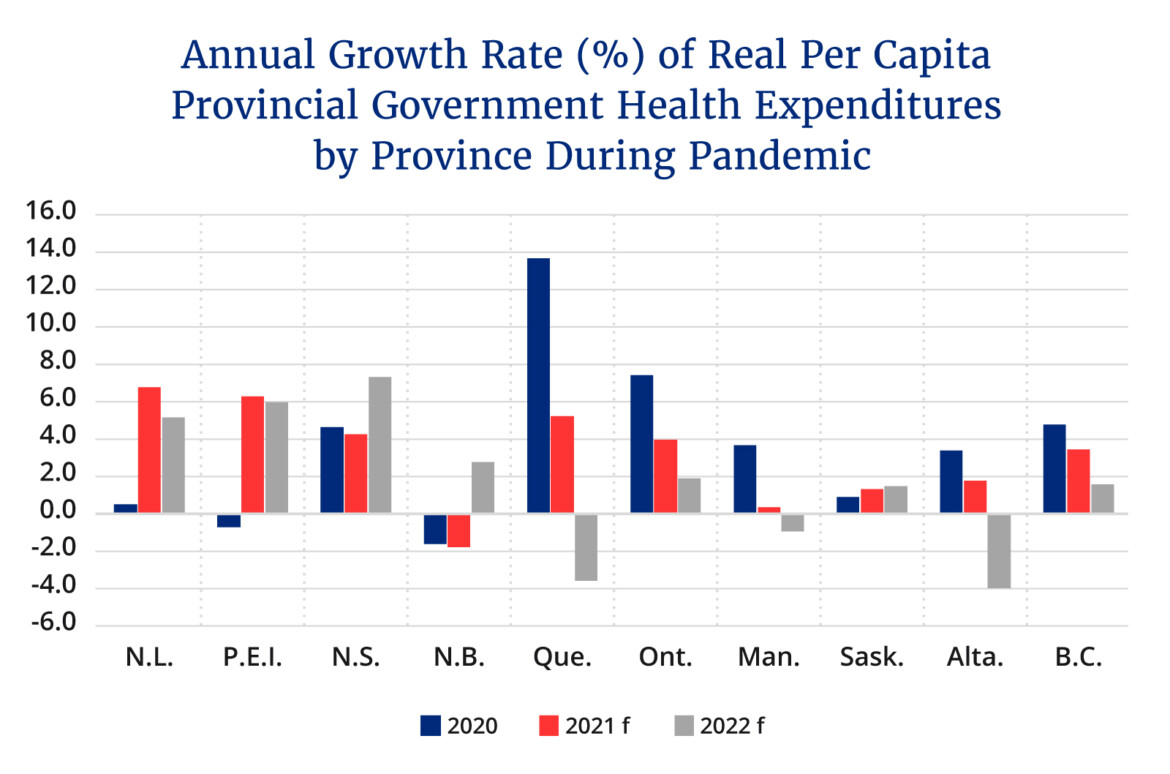

Estimates for 2022 see real per capita provincial government health spending declining, though at a much smaller rate than total health spending. Figure 4 illustrates that this decline will not be uniform across individual provinces with the four Atlantic provinces, Ontario, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia seeing increases while Quebec, Manitoba, and Alberta are expected to see decreases. While much is made of the importance of federal cash transfers to fund health care, it remains that spending differences across the provinces are also a result of provincial government choices with how they wish to deploy their own source revenues and resources.

The picture going forward from 2022 will see upward pressures on health spending just from population growth alone given Canada’s robust population growth that is the fastest in the G-7. As well, there are ongoing shortages of health human resources given the age distribution of the health sector labour force—nearly 20 percent are over age 55—which means a combination of post-pandemic burnout and retirements are driving increased scarcity and pressure on wages and salaries. This scarcity is occurring at the same time as increased demand from the backlog of delayed diagnostic tests and procedures during the pandemic are dealt with. We are in the curious position of being one of the biggest spenders on health in the developed world and yet marked by growing shortages of services as well as mediocre performance on many health indicator outcomes compared to countries that are spending less than we do.

And so, the grand operatic performance that is the Canadian health system in crisis will continue. Inevitably, as autumn turns to winter and hospital emergencies are increasingly clogged with COVID and other rebounding respiratory system ailments, the media will present arias that dramatically chronicle the mounting crisis.

The provinces will then join in a unified choral performance repeating their perennial demands for increased health transfers from the federal government to address the situation. Finally, Ottawa will conclude the performance with a well-rehearsed and precise recitative resisting the handover of funds without conditions that are tied to outcomes it desires, moving the discussion and the problem forward to yet another fiscal year.

For Canada’s health system, tomorrow is yesterday.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes