Some voices have criticized the Trudeau government’s recent pledge to identify $15 billion in fiscal savings over the next five years as unserious and hypocritical after years of large-scale spending growth. They have a point: annual federal program spending has increased by 80 percent since it took office in 2015.

Yet if one has been critical of the Trudeau government’s high spending record, then he or she ought to support at least in theory its nod to finding fiscal savings. It could be far worse after all.

We don’t know much about the review at this stage. Treasury Board President Anita Anand has indicated that it will protect transfer payments to other orders of government as well as spending on Indigenous services and the Canadian Armed Forces. She’s also said that it will aim to minimize actual job losses by relying on attrition and redeployment.

Her main emphasis though has been that the government’s review exercise won’t be like the Harper government’s spending review following the global financial crisis which she claims involved “short-sighted cuts that had to be reversed.”

I may quibble with her characterization of those cuts (which I was personally involved in) but I agree that the Harper government’s post-recession spending review isn’t the right model for Minister Anand and the government to pursue. The goal of the aptly named “Deficit Reduction Action Plan” was to boost the government’s own efforts to constrain program spending in the name of eliminating the recession-induced deficit. It must be understood as having been principally about deficit reduction in the short term.

That is far less relevant in the current context. The deficit is far too high and the Trudeau government’s savings target is too low to make much of a meaningful difference to the annual deficit. It’s mostly about offsetting the net costs of the government’s ongoing spending ambitions.

A better comparison from the Harper era therefore is the government’s Strategic Review process which ran from 2007 to 2009 before it was suspended due to the global financial crisis. Strategic Reviews weren’t driven by deficit reduction goals. They were principally focused on controlling or limiting the growth of new spending by reallocating departmental spending from low- to high-priority initiatives.

They are a good model for conducting regularized reviews of pre-existing government spending and weighing the usefulness of existing spending against the demands for new spending. Individual ministers were empowered to carry out such a prioritization exercise on behalf of their own departments. The process was generally evidence-based and rigorous. Minister Anand should restore it to implement the Trudeau government’s newfound commitment to rationalizing program spending.

Under the Strategic Review model, roughly 25 percent of government spending was reviewed annually over a four-year cycle. Participating departments in a given year were identified in the early spring. They were given a spending base and 5 percent target from the Treasury Board Secretariat and required to conduct a self-evaluation of where they were expected to achieve these savings using of set of metrics including:

- Increase efficiencies and effectiveness: Do these programs and services deliver real results for Canadians and provide value for money?

- Focus on core roles: Are these programs and services aligned with the federal role or is another level of government or some other institution (such as the market or civil society) better placed to deliver them?

- Meet the priorities of Canadians: Are these programs focused on the needs and priorities of Canadians?

The results of these reviews were then presented to the Treasury Board Cabinet committee in the summer or fall in order to inform the budget process. Treasury Board Ministers were free to accept or reject the submissions of their colleagues but the overwhelming tendency was to accept them since individual ministers had full ownership of what spending cuts they ultimately put forward.

But remember the goal wasn’t necessarily to reduce spending as much as it was about controlling or limiting the growth of new spending. So while departments were required to identify their “lowest-priority, lowest-performing 5 percent of spending” for reallocation, they were also permitted to put forward alternative spending proposals for reinvestment.

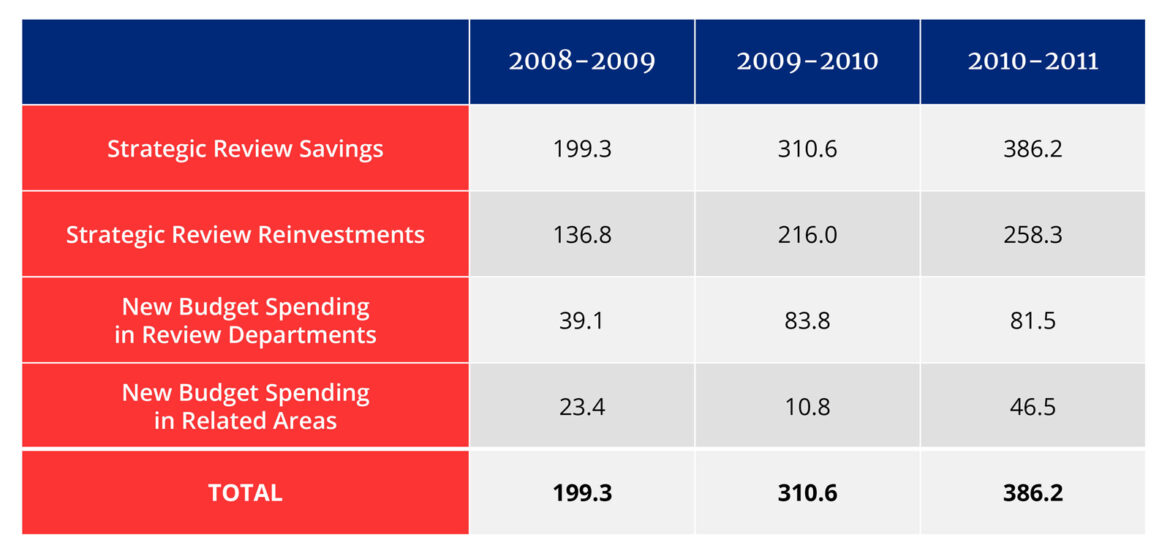

The 2007 experience is illustrative. Seventeen federal organizations (including departments and agencies) participated that year representing $13.6 billion in direct program spending or roughly 15 percent of all government program spending that was examined under strategic review. (The overall share of federal spending represented by the participating departments and agencies was a bit lower that year because it was a new process.) All identified savings were recycled back into the same departments or related areas (see Table 1). Basically, the government was able to use the Strategic Review process to control the growth of new spending through fiscal recycling.

TABLE 1: FEDERAL STRATEGIC REVIEW PROCESS, 2007 ($MILLIONS)

That the identified savings were “reinvested” mostly back into the departments created an incentive for ministers and their departments to buy into the exercise. They knew that their full participation would be rewarded by partially or fully funding their new priorities.

The key point here is that the Harper government’s fiscal objectives were not, by and large, the sole purview of the prime minister, finance minister, or Treasury Board president. There was a sustained commitment by every minister to scrutinize his or her own spending and to prioritize any requests for new spending within the government’s broader agenda.

My past experience in the prime minister’s office and the minister of finance’s office is that such system-wide buy-in is crucial for such an exercise to ultimately be successful. A government may be able to impose fiscal constraints on itself through a combination of public pronouncements, legislative targets, or internal processes. But a system-wide commitment to limiting new spending requires dedication and focus from the Cabinet and even the governing caucus. It won’t happen if Minister Anand is pushing this agenda on her own.

This is especially true for the Trudeau government in which ministers and their departments have been socialized to believe that there are no fiscal trade-offs because new and more resources can be taken for granted. Resetting such a spendthrift culture will require more than a top-down “weed-whacking” exercise that extracts some marginal savings but otherwise leaves internal expectations and norms firmly in place. The risk is that such an outcome is overwhelmed by new, incremental spending in subsequent budgets.

What’s needed instead is a new bottom-up culture in which every minister believes that he or she is personally invested in the government’s fiscal management. Institutionalizing the Harper government’s Strategic Review model can help to rebuild such an internal culture in favour of fiscal priority-setting and overall budget discipline.

If the Trudeau government is indeed serious about its newfound commitment to “sound economic and fiscal stewardship”, then it should be lauded for a much-needed course correction. One test of its seriousness is if it’s prepared to restore its predecessor’s strategic reviews.

Recommended for You

‘A good speech—but not a lot is new’: Did Poilievre’s big speech on Trump, China, and the economy hit the mark?

DeepDive: Can we survive the journey to AI abundance?

‘Riding the storm out’: Alberta’s budget reveals why oil revenue volatility makes fiscal planning impossible

Poilievre stays the course on Trump—but is it enough?