It’s been a remarkable couple of weeks in global bond markets, possibly some of the most consequential since the Great Financial Crisis. All of a sudden, seemingly out of nowhere, the yields of longer-duration debts have exploded higher. The implications for the economy, for governments, and for consumers are far-reaching. We are in the midst of a highly consequential moment that presages a difficult period ahead for Canada. Let me explain.

Representing the risk-free rate of return, U.S. government bonds are the benchmark that all other asset classes from equities to real-estate to mortgages to corporate and government debt are priced against. Simply put, the rise and fall of Treasury yields determine the cost of capital for everyone and everything. No other market is more consequential for the global economy.

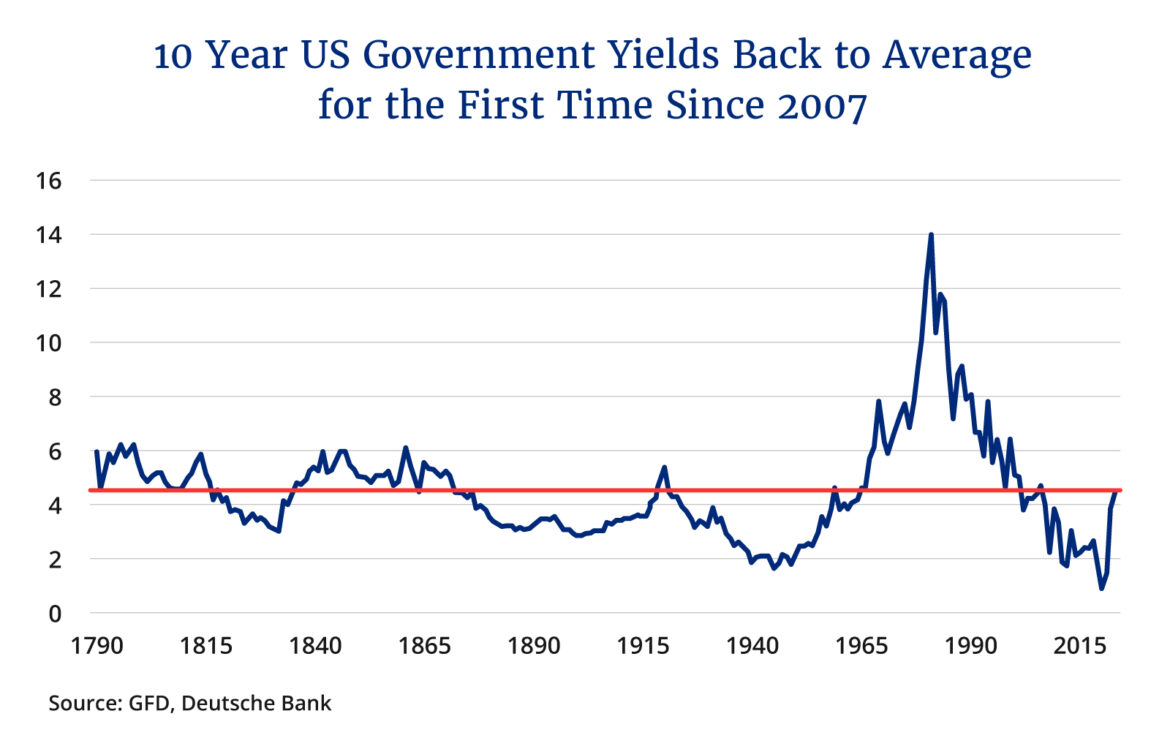

This past week the ten-year U.S. government bond surged above 4.85 percent, a yield not seen since the 2000s. In short, investors are now asking for significantly larger returns on so-called “risk-free” U.S. government debt than at any time in the last two decades, and quadruple what they were willing to take just two short years ago in the depths of the pandemic.

Why are yields soaring on government debts, not just in America but across the world’s major economies? Part of the answer lies with inflation. Higher rates of inflation eat away at the value of bonds as the investor’s principal is paid back in the future dollars, loonies, and euros of the issuing governments. But this isn’t the whole story as long-term inflation expectations haven’t shifted significantly with the long-run rate stable at 2.5 percent, according to a variety of market measures.

There are many alternative theories as to why bond yields are soaring, ranging from the Federal Reserve running down its own massive bond holdings, to the chilling effect the confiscation of Russia’s debt holdings had on foreign buyers of U.S. Treasuries, to the inflationary effects of higher oil prices. All likely have some impact, but the more plausible explanation is the simplest one: we are witnessing a powerful mean reversion in global bond prices.

The recent surge in yields is a strong signal that Western economies have exited an unprecedented period of ultra-low inflation and its corollary: central bank engineering of lower bond prices. Add in high debt-to-GDP ratios across the developing world, the Ukraine War, deglobalization, the reshoring of supply chains, the greening of the economy, and the resulting government deficit spending from all of the foregoing and you have the ingredients for bondholders to demand (and get) higher yields for the foreseeable future.

This trend matters because it runs opposite much of the conventional wisdom, as distilled in our own prime minister’s recent opining that “…interest rates are going to start coming down by the middle of next year.”

Yes, conceivably the Bank of Canada could start to cut its overnight lending rate if inflation miraculously evaporates in the coming months (Friday’s blowout job numbers suggest this isn’t likely to happen any time soon), or the country enters recession.

But what policymakers like the prime minister are seemingly failing to grasp is that longer-duration debt yields that directly affect consumers, corporations, and government are surging because of larger structural forces in the global economy that show few if any signs of abating. In short, “higher for longer” is not just the mantra of central banks, it is fast becoming Mr. Bond Market’s new credo.

The smart way to think about bond yields is that they have three key components. The first is longer-term inflation expectations which remain generally anchored. The next is what economists call r*, or the neutral short-term interest rate that central banks would set if they wanted to neither impede nor encourage growth. The last component is the term premium or the additional yield that investors require to compensate them for holding the bond to maturity (e.g. bonds unlike equities return all of the original capital invested at the end of their term).

The reason why it is likely that the recent surge in yields will translate into “higher for longer” interest rates where it hurts or the longer duration parts of the yield curve that affect real-estate prices, corporate borrowing, and government debt servicing costs is because of changes to r* and the term premium. Both together traditionally counted for two percent or so of longer duration Treasury yields prior to the GFC. Both then collapsed and stayed at basically zero until last year. Now both are rising. R* because of large, continuing deficit spending on the big structural adjustments Western economies face from reshoring, de-globalization, and decarbonization. The term premium because these deficits are now getting sizable in historic terms vis-à-vis total outstanding government debts and have become seemingly permanent. Add in continuing inflation and growing political dysfunction in the U.S. and understandably bondholders want to be compensated for more risk.

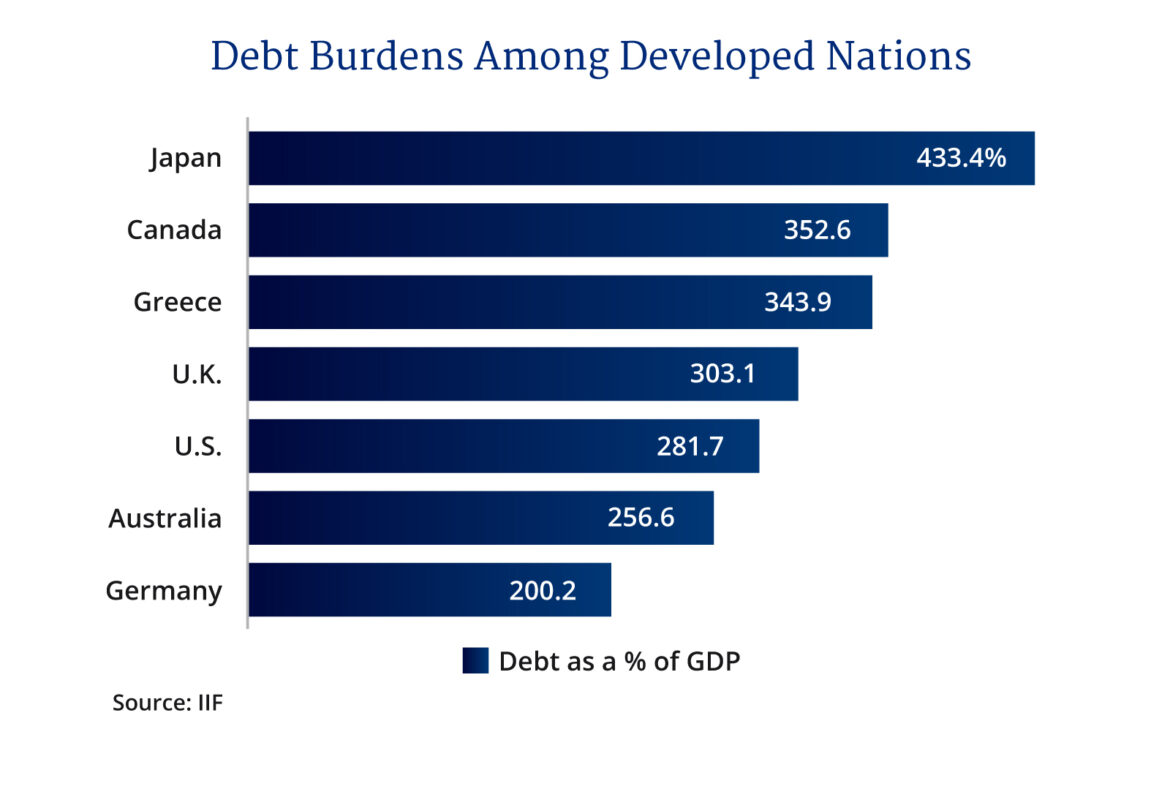

Reversion to the historical mean in bond yields matters for Canada. We are one of the most highly leveraged economies in the world. In recent years, when measured by our total debt of governments, households, and non-financial corporations as a percentage of GDP, we are ahead of Greece and behind only Japan. Our economy is massively over-reliant on a single highly interest-rate-sensitive asset: housing. And, we don’t have the exorbitant privilege of a reserve currency, and as such our domestic bond yields must approximate the United States if we want to attract investors to buy our debt and finance now seemingly perpetual government deficits.

All of us—homeowners, businesses, and governments—should be tuning out wishful thinking that low rates are just around the corner and start preparing for higher bond yields for the long term. To the point: the future trajectory of borrowing costs isn’t just about inflation expectations and rate setting by our central bank anymore. What the $133 trillion bond market has been telling us loud and clear these past couple of weeks is that its participants believe a reversion to a pre-GFC cost of capital across Western economies has arrived and it isn’t going away anytime soon, whatever our prime minister might think.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes

Stephen Staley: Widespread deregulation is Canada’s golden ticket for economic growth