The world is a dangerous place with many enemies that would do us physical harm or eat our economic lunch. The war in Ukraine has shown us the importance of having strong alliances with countries that have common political, economic, and social goals and are willing to unite to fight for democracy.

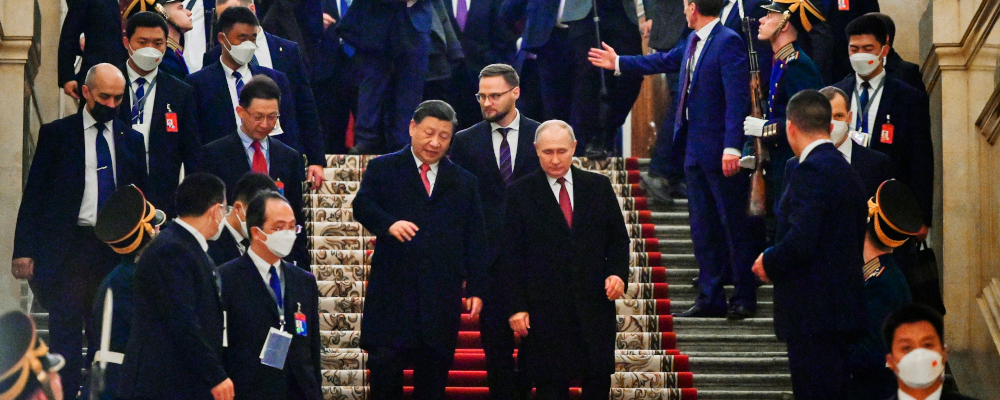

The alliances being formed or augmented are geopolitical, economic, or military and usually reflect the shared goals and values of its members. While alliances are formed by friendly countries to stand up against common enemies, more often now, the enemies of my enemy are banding together as “friends”. It is often a fool’s friendship. Today we see an expansionist Russia courting Iran as a partner in terror. China is trying to dominate the world through economic dependence and growing military might, making it ultimately easier to invade Taiwan. As we try to counter this aggression there are lessons to be learned from our not-too-distant past.

Hitler made a non-aggression pact with Russia in 1939 allowing Stalin to annex half of Poland and a number of Baltic countries. The reprieve was short-lived since Hitler soon attacked Russia, which was always his longer-term plan. It forced Stalin to side with the Western Allies until, at great human cost, the war was won. The Russian friendship of convenience with the Allies was also short-lived as the post-war USSR annexed 15 states in a growing military expansionist threat. These states were part of a growing and powerful Eastern Bloc that grew to include communist and socialist states in Africa, Asia, South America, and Cuba.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was also formed shortly after the end of WWII in response to the growing Soviet threat. Its three proclaimed goals were deterring Soviet expansion, suppressing a revival of European military nationalism, and encouraging European political integration. In 1949 NATO had 12 founding members of the Alliance. This grew to 15 when the Federal Republic of Germany was allowed to join in 1955, ending its status as an occupied country.

With the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union, many former satellite Eastern Bloc countries became independent democracies and joined NATO to protect them from future Russian dominance. The current Russian war in Ukraine was meant to constrain NATO’s growing influence and allow Russia to again dominate Ukraine and control its considerable assets. The Russian tactics of terror and indiscriminate civilian attacks have led not just to fierce Ukrainian resistance, but also to the realization that neutrality for many countries was unwise. Now with the most recent addition of Finland, a country with a 1,350-kilometre border with Russia, NATO comprises 31 countries, united in common goals and declaration of mutual military support. Soon Sweden will be the 32nd member.

Canada has played an outsized role in NATO politically, if not financially. In 1956 Lester B. Pearson, our foreign minister and eventual prime minister, was one of the “Three Wise Men” who drafted a report on non-military cooperation in NATO, published in the wake of the Suez Canal Crisis. This heralded NATO’s efforts of peaceful conflict resolution backed by a strong joint military presence.

In the last several decades China has continued to grow economically and militarily, using economic policy rather than military alliances as a way to increase its global influence. It has developed a Belt and Road Initiative, a strategy of economic support with financial investment in more than 150 countries and international organizations. This allows China to have an ever-growing role in global foreign policy, albeit with the risk of an economic stranglehold on many poorer countries, known as “debt-trap diplomacy”.

Abraham Lincoln said, “A friend is a man who has the same enemies you have”. Sometimes the enemy of my enemy is my friend, but often it is not. Currently, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia are united in protecting a stable oil supply and combatting Islamic terrorism. However, don’t confuse a friendship of mutual convenience with being a trusted friend. Saudi Arabia remains a monarchy that allows terrorist funding to thrive and whose leader thinks nothing of murdering and dismembering a political critic. As the Kingdom perceives changing U.S. priorities and constantly shifting politics under different presidents, it is trying to forge competing alliances to protect it from Iran, its greatest threat.

As a result, Riyadh, in a deal brokered by China, has resumed diplomatic relations with Iran in an attempt to lessen tensions through diplomacy. The Saudis have also increased relations with China in order to partner with a country that has greater leverage over Iran than the U.S. and to reduce the need for costly military conflict. Iran of course gains by reducing the need for cooperation with Israel, a country it has pledged to destroy and to weaken the effects of international trade sanctions.

The Abraham Accords represented a different path towards greater peace in the Middle East, linking countries at risk from Islamic terrorism. Brokered by the U.S. and signed in 2020, it represented an important normalization and restoration of diplomatic relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and later Morocco. The accord doesn’t imply friendship between the countries but acceptance that greater economic cooperation can lead to political stability.

We need to find ways to use diplomacy and economic accords to find peace and avoid war. We can take reasonable measures to lower tensions and turn down the heat. We do have to remember that the enemies of our enemies are not always our friends, but rather convenient partners…until they are not. Some countries such as Russia, Iran, North Korea, and terrorist organizations have the long-term goal of destroying democracy. Perhaps only regime change can alter their threat.

The fable of the scorpion and the frog is a lesson in not believing the false words of our enemies when they pledge to work together with us. A scorpion asks a frog to carry him over a river. The frog is afraid of being stung, but the scorpion argues that if it did so, both would sink and drown. The frog agrees, but midway across the river, the scorpion does indeed sting the frog, dooming them both. When asked why, the scorpion points out that it is simply its nature.

As we try and make the world a safer place we have to value our true friends and be careful of friends of convenience, who may only be the enemies of our enemies. Einstein said, “The world will not be destroyed by those that do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything.”

We can’t let the glitter of economic ties with China blind us, allowing them to interfere in our elections, passively steal our technology, or militarily bully other countries. We have to continue to thwart Russian aggression by continuing strong support for Ukraine, despite its ongoing cost. Iranian support of terrorism and repression of human rights isn’t something to overlook as we try to reduce tensions. Diplomacy works best when the hand that reaches out is an iron fist in a velvet glove. It shows our enemies and even the enemies of our enemies that while we favour peace, we are prepared to fight with all our resolve for what we believe in.

Recommended for You

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

David Mulroney: Foreign Minister Joly, Xi Jinping’s China doesn’t do ‘dialogue’

J.L. Granatstein: Trudeau’s submarine charade

Amal Attar-Guzman: Canada’s global leadership is waning. Why not expand our influence closer to home?