One of the oddest traits of the Trudeau government is that even after seven and a half years in office, it still cannot decide whether to boast about its fiscal profligacy or downplay it. On one hand, its extraordinary willingness to “invest” public dollars in different causes and projects is clearly core to its political identity. On the other hand, it seems self-conscious about the true costs of its progressive predisposition to public spending.

This inherent tension is not new for the government. It goes back to its origins. The Trudeau government was first elected with a plan for deficit spending that it went some lengths to emphasize was “modest”, “prudent” and “short-term.” Even as mounting evidence contradicted these claims (as former Prime Minister Stephen Harper famously predicted), it seemed reluctant to fully embrace its own fiscal policy choices. The government and its supporters clung for some time to claims about the federal debt-to-GDP ratio and other fiscal anchors before eventually abandoning them altogether.

Today they’re still stuck between two competing ideas: the government rhetorically rejects the so-called “austerity” of the Conservatives but it also counterintuitively argues that its fiscal policy broadly conforms to its predecessor’s.

That leaves it to us to try to reconcile these incongruous interpretations of the Trudeau government’s fiscal policy. Let me therefore defend the government from its progressive critics and its own preposterous spin about “fiscal restraint” as Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland put it in her 2023 budget speech.

There’s nothing restrained about the government’s fiscal policy unless the word has assumed such an elastic definition as to render it essentially useless as a description of government budgeting. Notwithstanding the claims of its critics and defenders, the Trudeau government is easily the biggest-spending government in modern Canadian history.

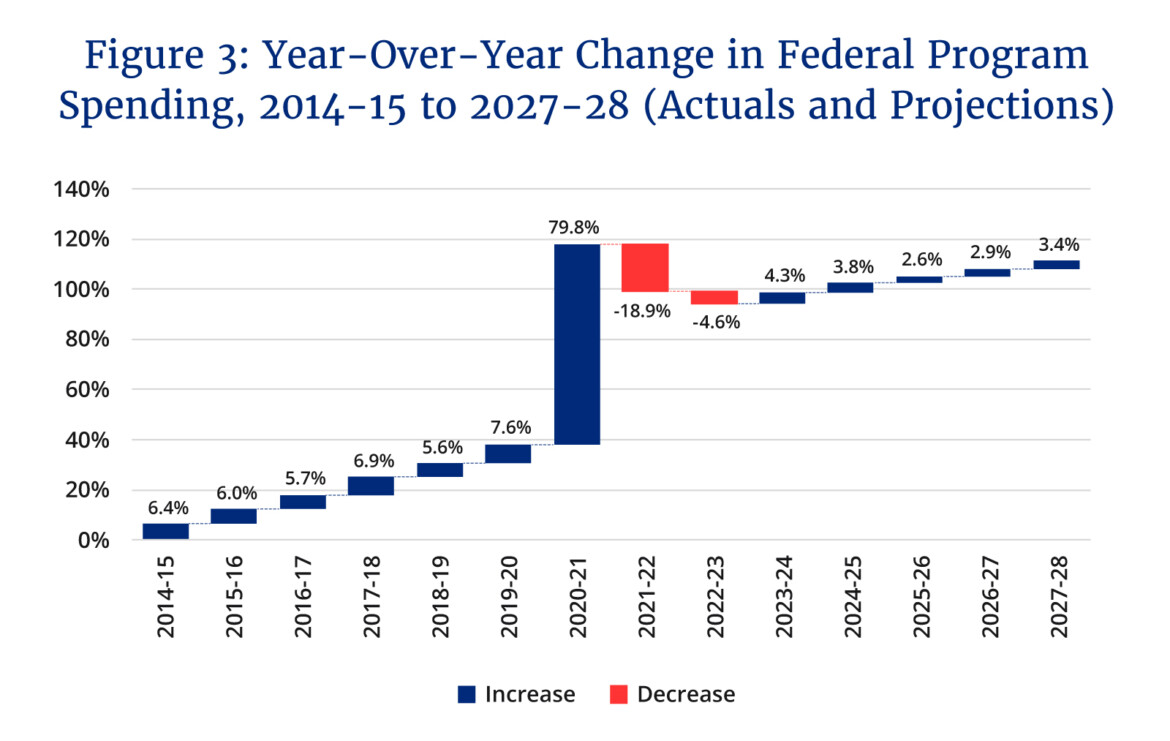

The COVID-pandemic obviously complicates an analysis of the government’s fiscal record. The unprecedented spike in federal spending—it increased by nearly 80 percent between 2019-20 and 2020-21—needs to be accounted for. Yet even if one opposed the magnitude of overall pandemic spending or specific spending choices, it’s fair to say that any government would have increased program spending and run budgetary deficits of some size in response to the pandemic.

Fiscal figures beyond 2020-21 are also still only projections that the government may overshoot. It has a long track record of pushing up spending and the size of the deficit as the budget’s outer-year projections become closer to the present. The 2023 budget for instance revised the government’s previous projection that it would be back in surplus in 2027-28. The Parliamentary Budget Office’s analysis now suggests that it may happen by 2035. The point here is that there’s good reason to assume that current spending projections for 2023-24 and beyond are bound to be adjusted upward in the coming years.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we can still look backwards and forwards to evaluate the Trudeau government’s fiscal policy and the tension that’s run through how it has spoken about spending, deficits, and debt.

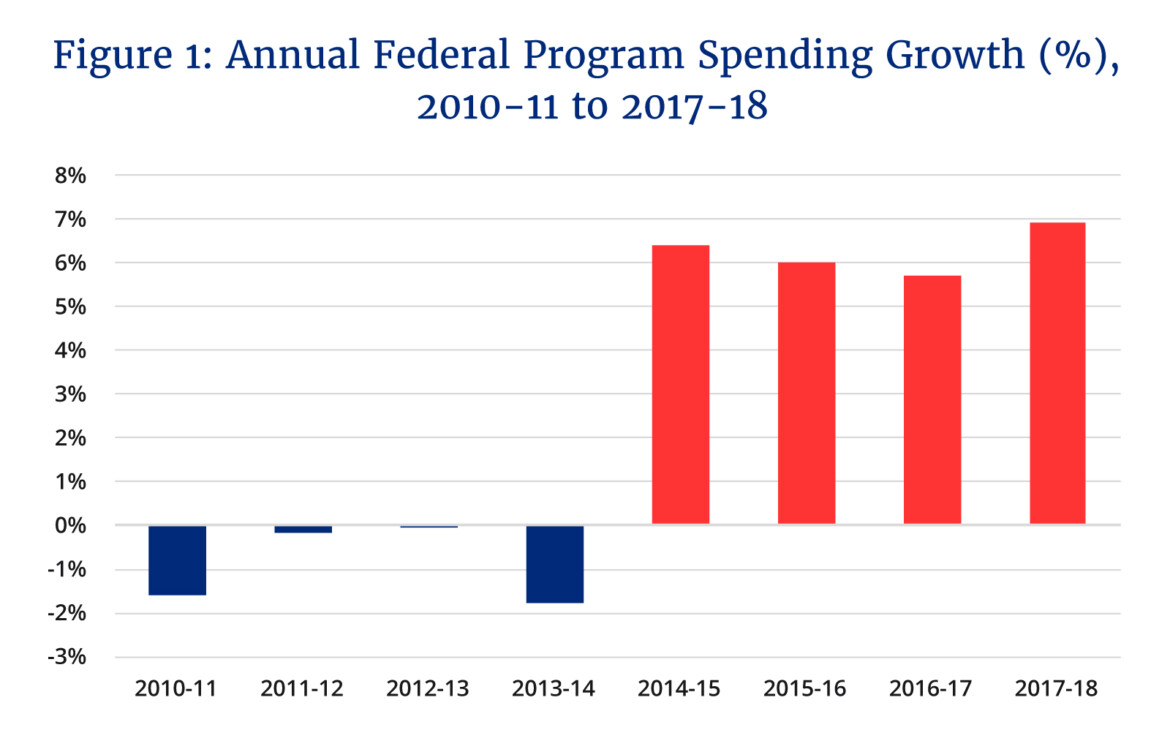

Let’s start with program spending prior to the pandemic. It grew by an average of 6.2 percent per year over the Trudeau government’s first four years in office. This stands in contrast with the Harper government’s last four years which actually saw program spending decline by an annual average of 0.9 percent (see Figure 1).

Then there’s the pandemic response which drove up federal spending to unprecedented levels. Just consider: the 2020-21 deficit itself was more than 10 percent larger than the entire federal budget in the last year of the Harper government. Another way to think about it is: its predecessor could have collected no revenues in its final year in office and still ran a smaller deficit than the one recorded in 2020-21.

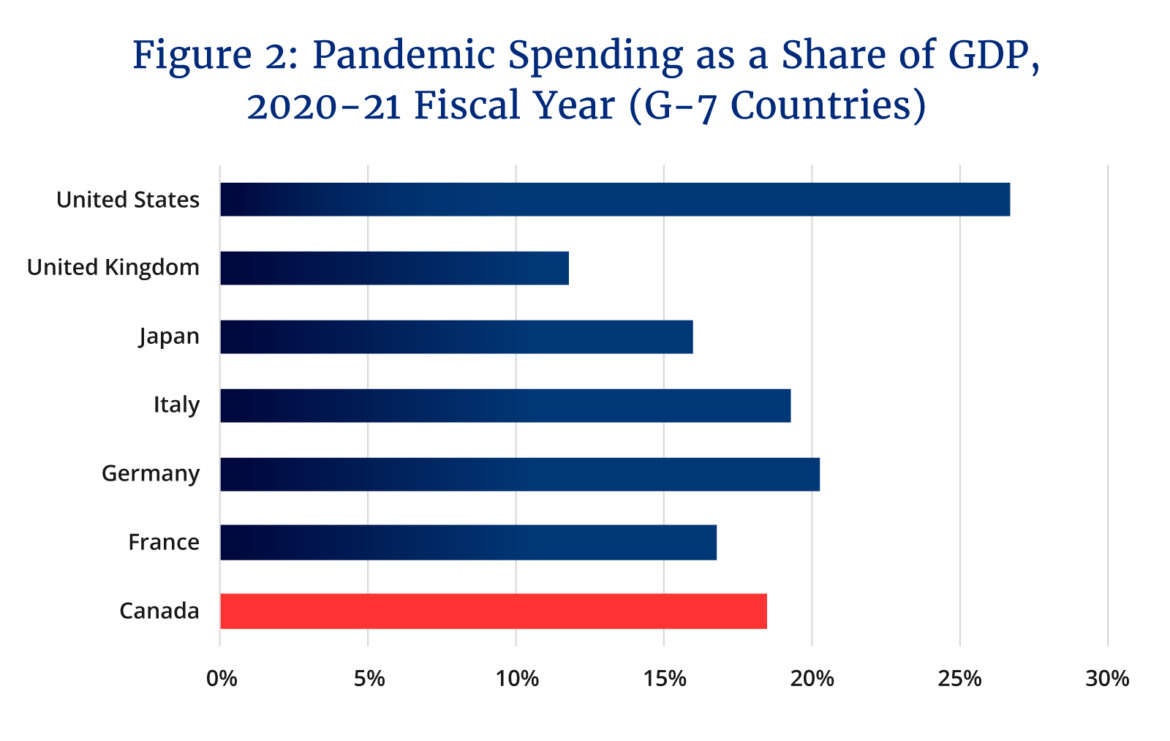

Emergency spending as a share of GDP reached 18.5 percent that year which though it matched the G-7 average (see Figure 2) was among the highest in the world including peer jurisdictions such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

The government’s post-pandemic projections envision program spending falling relative to a pandemic-induced high but it’s notable that it doesn’t fully revert to its pre-pandemic trajectory. After a nearly 80-percent increase in 2020-21, the government projects a roughly 25-percent reduction over the next two years before it resumes growing again. A considerable share of the pandemic spending has simply become part of the government’s ongoing expenditure baseline.

As I’ve outlined in a past Hub article, if the pandemic had never happened and the government simply kept growing spending at roughly 6 percent per year as it had prior to the pandemic, program spending in the current fiscal year would be as much as $45 billion lower than is currently projected (see Figure 3). Such back-of-the-envelope analysis provides a sense of how much the pandemic spike has altered the course of the government’s own pre-pandemic trajectory.

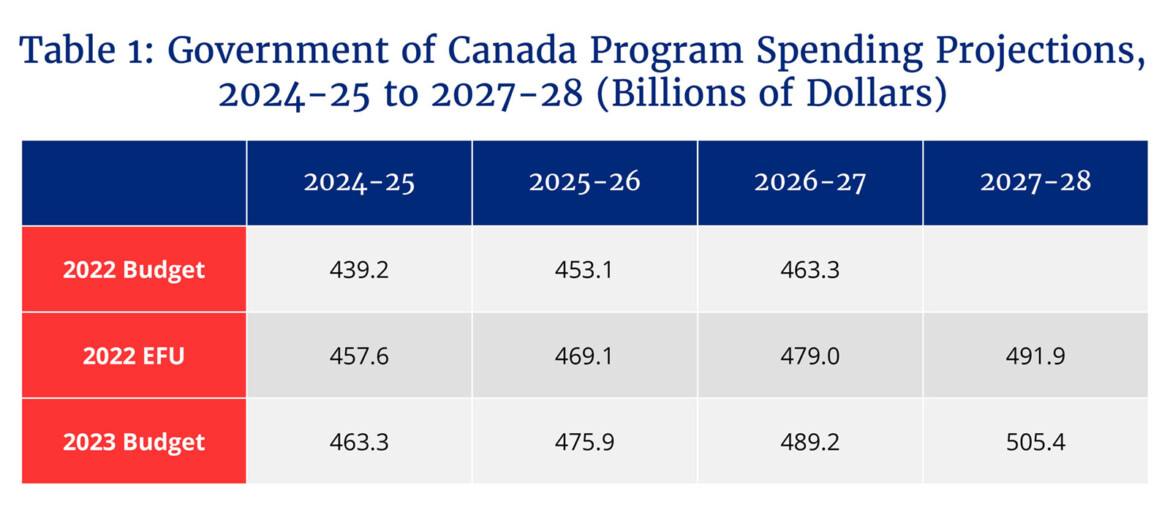

As mentioned earlier, there’s good reason to be skeptical about the post-2023-24 projections. They anticipate a level of spending restraint that the government has never delivered. They’ve also already changed a great deal in the past 16 months alone.

Consider for instance that between the 2022 Budget, the 2022 Fall Economic Statement, and the 2023 Budget, projected program spending in 2024-25 alone has gone up by nearly $25 billion (see Table 1). Another way to put it is: between the past two budgets alone, the government’s own projection for program spending in 2026-27 was pushed up three years to 2024-25. Even if one is prepared to grant the government some dispensation due to pandemic uncertainty, it’s difficult to defend such significant movement—particularly in the later years—over such a short period.

These figures suggest that, as these outer years get closer, it’s more likely than not that the government’s own spending projections will grow. The interplay between outstanding policy priorities, political exigencies, and ideological preferences undoubtedly points in the direction of higher spending and more deficits and debt in the coming years.

The Trudeau government’s spendthrift assumptions were evident at its beginning and they remain evident today. At this point, the only ones unable to see it are those blinded by some combination of ideology or partisanship. The government might as well accept it. The rest of us have.

Recommended for You

Falice Chin: A tale of two (Poilievre) ridings

Evan Menzies: Calgary at 150: Why is it so hard to celebrate our history?

‘We’re winning the battle of ideas’: Conservative MP Aaron Gunn on young men moving right, the fall of ‘wokeness,’ and the unraveling of Canadian identity

Laura David: Red pill, blue pill: Google has made its opening salvo in the AI-news war. What’s Canadian media’s next move?