There is a moral rot in this country.

There are three causes for this spreading decay: moral relativism, apathy, and isolation. Moral relativism reveals itself when we reject objective, universal truth. In other words, it is when we ignore things that we all know to be right or wrong based on our consciences and thus act immorally. This is universal in that people of all cultures and all religious traditions know these things to be true.

When I was quite young I once stole a friend’s Happy Days pin (yes, I am that old) because I liked it and I thought I should have it instead of him. The fact that I wanted it and thought it would look good on my jean jacket was a weak rationalization for what I knew in my deepest self, even at age five, to be objectively wrong. Thieves, murderers, or adulterers may employ all sorts of arguments to justify their actions, but in their deepest selves, they know these things to be wrong.

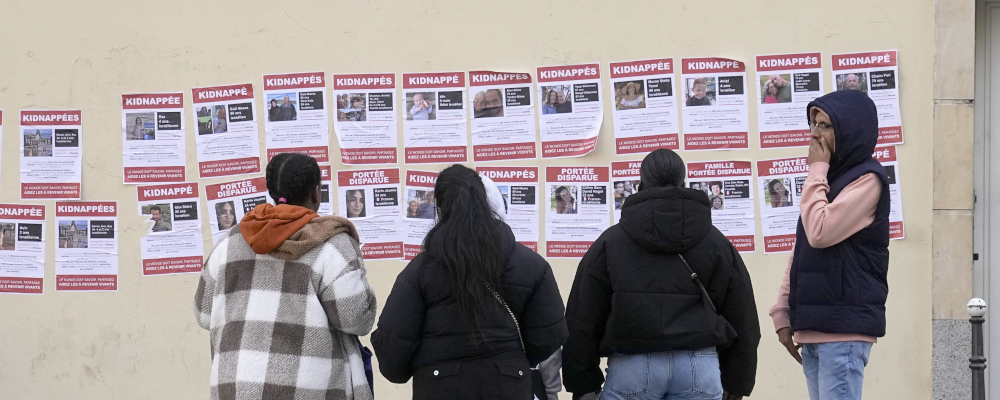

Likewise, those who have equivocated and remained silent, or worse, those who have glorified the brutal and sadistic murder, torture, and kidnapping of innocent Israeli men, women, and children by Hamas last week know that these brazen acts of terror are objectively and universally evil. Yet, blinded by political ideologies, including a neo-Marxist cultural view that divides people into so-called “colonial oppressors” versus “oppressed,” these barbaric acts are freely justified and promoted in Canada in protests and via equivocating, spineless statements by some of our public institutions and their leaders.

These individuals, our fellow Canadians, know better. As the Catholic philosopher J. Budziszewski wrote in his seminal 2003 book What We Can’t Not Know:

The common moral truths are no less plain to us today than they ever were. Our problem is not that there isn’t a common moral ground, but that we would rather stand somewhere else. We are not in Dante’s Inferno, where even sinners acknowledge the law they have violated. We are in some other hell. The denizens of our hell say that they don’t know the law—or that there is no law—or that each makes the law for himself. And they all know better.

One offspring of moral relativism is apathy. The apathy in our culture manifests in individualist sentiments such as “It’s none of my business,” or “Why should I get involved?” It betokens a breakdown in human community and a prideful inability to recognize when something is wrong. Silence and inaction are the symptoms of apathy. When we fail to condemn the murder of innocents, when we fail to condemn antisemitic hatred, and when we fail to speak out on behalf of our Jewish neighbours we have contributed to the rot; we have allowed it to fester.

Such apathy is also a manifestation of the isolation that exists in our society, an isolation that has deepened in the post-pandemic moment. As we isolate ourselves from one another ideologically, ethically, religiously, and physically we are no longer able to build deep human community that can address the differences that define our pluralism. Pluralism can never be about sameness, which is false equity. Pluralism has difference embedded in it.

This does not come without its challenges, including some particularly vile manifestations as this past week has revealed. But, when we isolate ourselves into our petty ideological worlds, our virtual hovels, and our little hermetically-sealed boxes of safe-ness, we rob ourselves of genuine face-to-face community with incarnate human beings with whom we are called to build and share a common life in Canada. If I can no longer see my Jewish neighbour as a friend, a colleague, or a classmate, but rather as an enemy and not as a fellow human being, then the rot will continue to eat away at our common life.

The English writer G.K. Chesterton was once asked by a British paper what, in his view, is wrong with the world. Chesterton wrote, “I am.” Such a humble response is what we clearly need these days, but given the radical individualism of our society could many of us answer similarly? If we are to halt the moral rot we see around us in our culture, we have to cut away the rotten bits so that a healthier, more deeply human culture can emerge.

To do this we must dedicate ourselves to formation in the virtues and to living virtuous lives. Virtues such as prudence, justice, and fortitude are in very short supply these days. Prudence rightly exercised shapes my conscience so that I recognize that celebrating (or being silent about) mass atrocities against Jews is abhorrent and beneath me as a human being.

Fortitude shapes my conscience such that I stand up and speak out courageously against evil and lies wherever I encounter them, for the good of our human life together. Justice is what I aim to promote when I see these deep ills of society and desire their remedy. Let us stem the moral rot we see and begin to build true solidarity in a more human culture in this country.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Peter Menzies: The mainstream media should love Doug Ford, now that he’s subsidizing them