Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland described the federal government’s fiscal update last week as a “responsible fiscal plan” that “reduced the deficit faster than any other country in the G7” and “builds on the $15 billion in public service spending reductions announced in the spring.”

Opposition leader Pierre Poilivre disagrees, pointing to “$20 billion in costly new spending” that increases inflation, public debt, taxes, and more.

For one, it was restraint; for the other, extravagance.

There’s truth in both perspectives.

Rising deficits

While the projected deficit did not grow this year, future ones rose considerably. Instead of totaling $130 billion between now and 2027, as projected in the last budget, the deficits are now roughly $170 billion.

If one looks back a full year, the rise is even sharper.

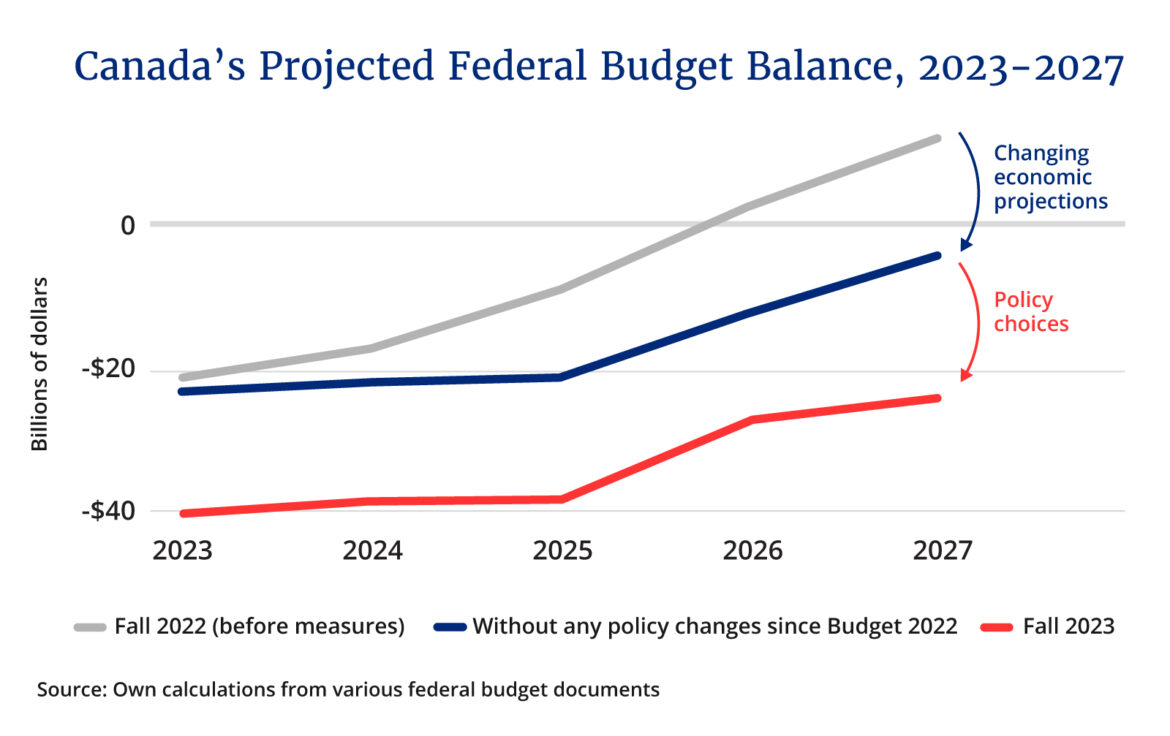

In the fall 2022 update, prior to new policy measures, the government anticipated total deficits between 2023 and 2027 of only about $30 billion—and a return to decent-sized surpluses at the end of those five years.

Compared to today, that’s a roughly $140 billion deterioration in Canada’s federal fiscal position. Some of this is due to worsening economic projections beyond the government’s control. But that’s only a small part of the story.

I estimate that had no policy changes occurred since last year’s budget, the total deficit between 2023 and 2027 would have come in at around $80 billion (up from $30 billion). That means roughly two-thirds of the deficit’s rise over this period is due to the government’s own choices.

If that’s the extravagance, where is the restraint?

Zooming in on the federal budget

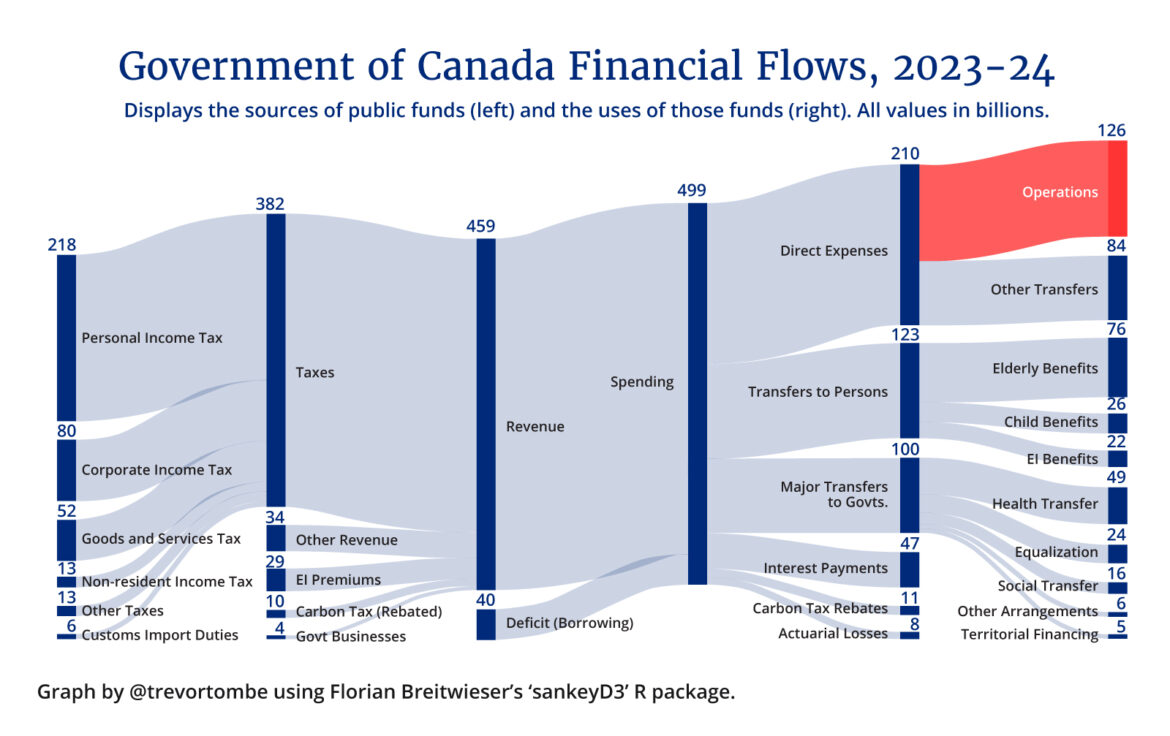

Most of us don’t appreciate just how little the federal government actually does, relative to the size of its budget. Of the nearly half a trillion in federal spending this year, only one-quarter of it is on direct government operations. I illustrate this below.

It’s here where you’ll find restraint.

Excluding transfers to people and provinces and interest on the debt, I estimate the federal government plans to spend nearly 24 percent less per person over the next six years. Down from roughly $6,270 per person in 2022 to less than $4,770 per person (adjusted for inflation) in 2028. That’s a significant reduction.

The trouble is, restraining direct federal expenses doesn’t get you very far.

In fact, you could fire every single federal employee (excluding the military and RCMP) and still come up short!Total wages and salaries paid to government employees, for example, were just over $56 billion last year. Excluding the military and RCMP, however, this amounts to less than the current $40 billion deficit. You could defund the CBC, privatize Via Rail, eliminate any program with the word climate or energy efficiency in the title, close every single regional economic development agency, and disband the entire Department of Canadian Heritage, and the deficit would be cut by barely more than one-fifth.

To really make a difference, you have to consider transfers.

The fiscal elephant in the room

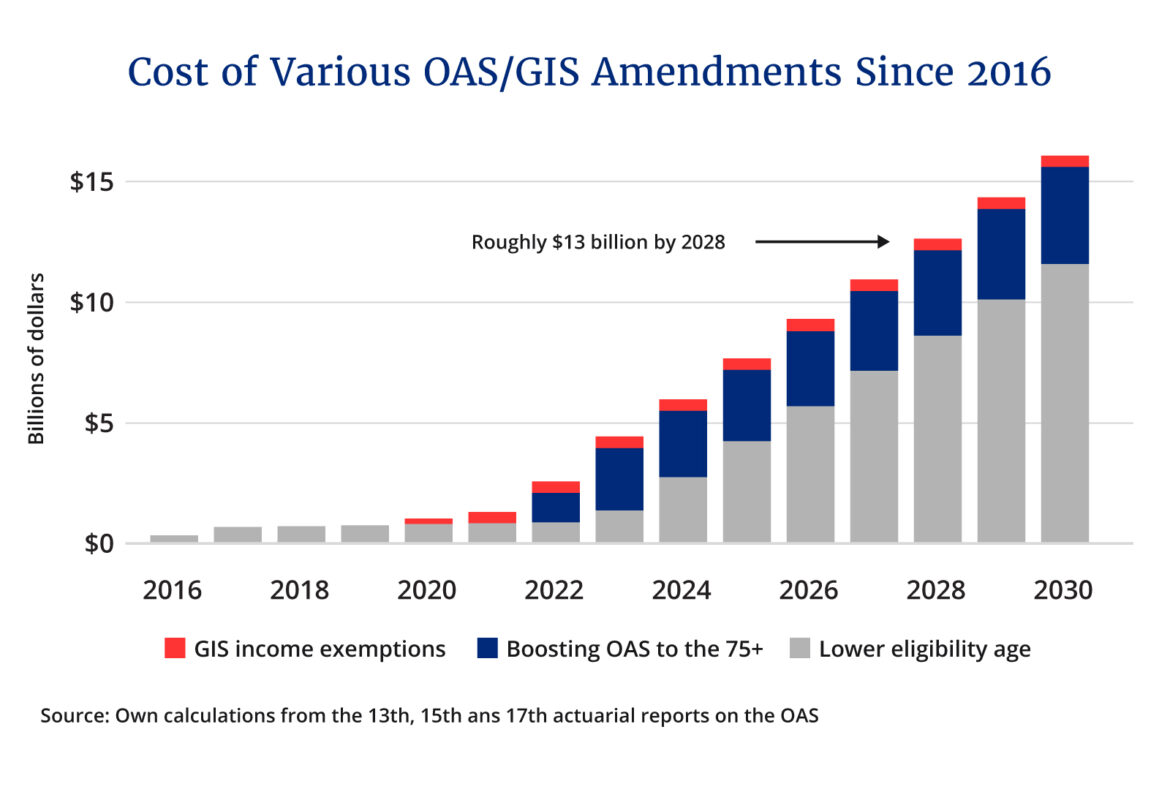

The largest contributor to rising federal spending is seniors benefits.

These are rapidly growing, not only because our population is aging but also because the federal government keeps ratcheting up how much it pays. As I illustrate below, policy decisions to boost payments will cost nearly $50 billion over the next five years. By 2028, fully two-thirds of the entire federal deficit will be due to these increases alone.

Avoiding these costs doesn’t have to mean increasing the eligibility age (although there is an exceptionally strong case for doing so). There are other ways.

A recent Globe and Mail editorial, for example, made a wise suggestion: trim benefits to high-income seniors. I estimate that approximately $6 billion in OAS and GIS payments flow to families with combined incomes above $150,000. By 2028, that could approach $10 billion. Combined with eliminating the 10 percent boost for seniors over 75 (which only started last year), the federal government could save roughly $13 billion by 2028. The case to trim such benefits goes beyond the federal budget. High interest rates, after all, are primarily benefiting seniors—and high-income ones, especially.I recently estimated for The Hub that this year those over 65 are collectively earning nearly $20 billion more in interest income compared to last year.

Balancing the budget doesn’t require much else. Some modest additional direct spending restraint (growing 0.2 percentage points per year less than current plans) and small changes to federal transfers to provinces (say, eliminating the floor payments within the equalization system) would be enough to balance by 2028 and save roughly $4 billion in interest along the way.

Whatever you think of this particular idea, one thing is clear: if you see more extravagance than restraint in the latest fiscal update and prefer balancing the books sooner rather than later, then confronting the rapid growth of transfers is necessary.

Recommended for You

Darrell Bricker: The House returns—and the tests begin

‘Expectations remain high’: The biggest storylines facing Canada’s leaders as Parliament returns

DeepDive: Fixing the stagnation nation: A blueprint for Canadian economic renewal

The Weekly Wrap: Three pressing questions as Parliament returns