Canada’s lagging economic and productivity performance is no secret. Various articles in The Hub have highlighted it, most recently one by Sean Speer and Taylor Jackson. “At the heart of Canada’s economic malaise,” they correctly noted, “is low productivity growth.”

And last week, Bank of Canada Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers echoed this sentiment. In uncharacteristically strong language for a central banker, she said Canada’s “long-standing, poor record on productivity” is “an emergency” and that “it’s time to break the glass.” (It’s a really good speech; read it, I’ll wait.)

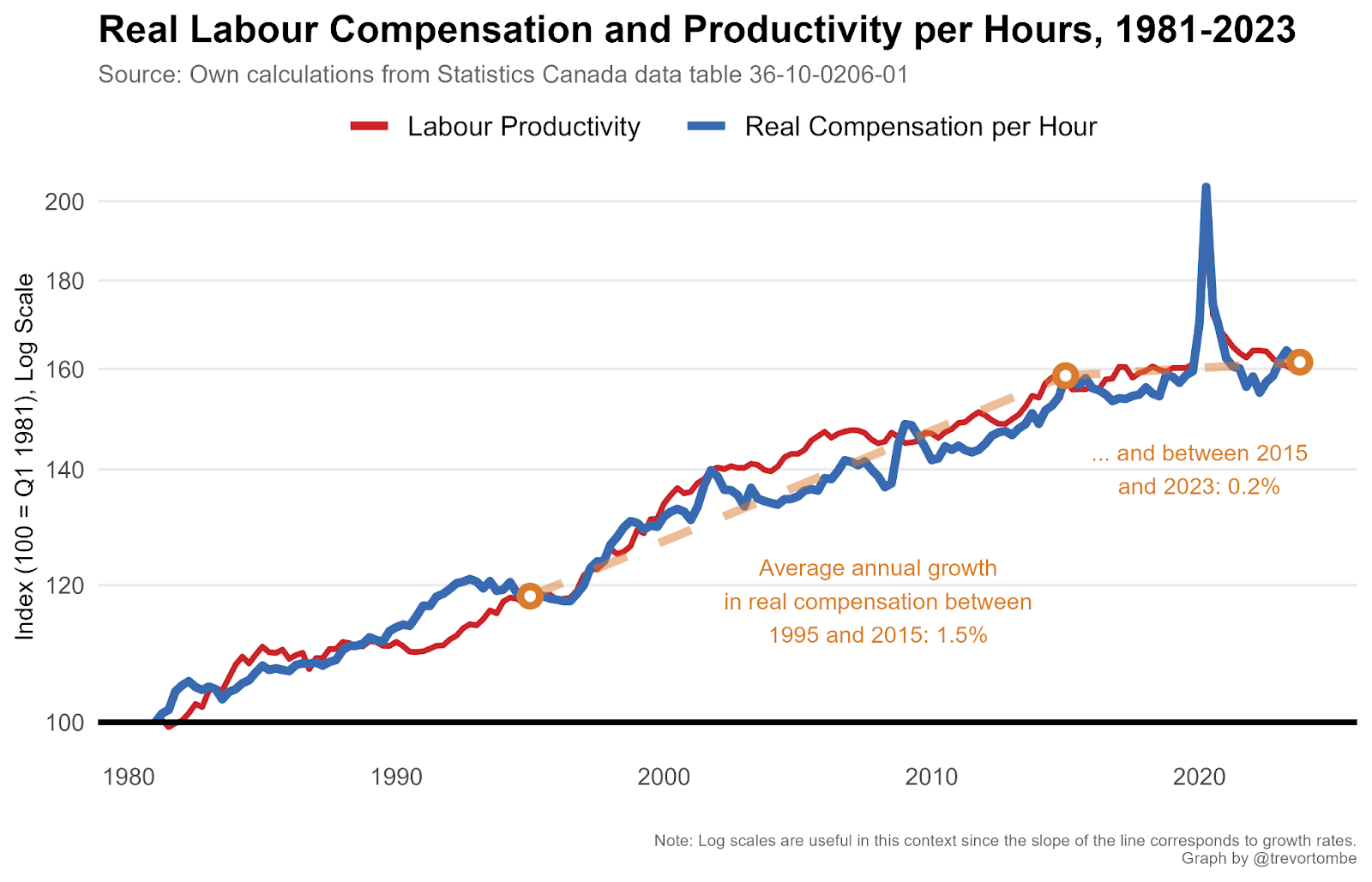

These are not exaggerations. Labour productivity has grown by 0.2 percent annually, on average, between early 2015 and the end of 2023. That’s the slowest growth over an eight-year period ever recorded. (At least since comparable data started in 1946.1The period between 1984 and 1992 came close, but still outperformed today.)

But this can be a difficult economic statistic for many to understand and, therefore, easy for political leaders to ignore.

So I want to draw attention to something much more concrete: income.

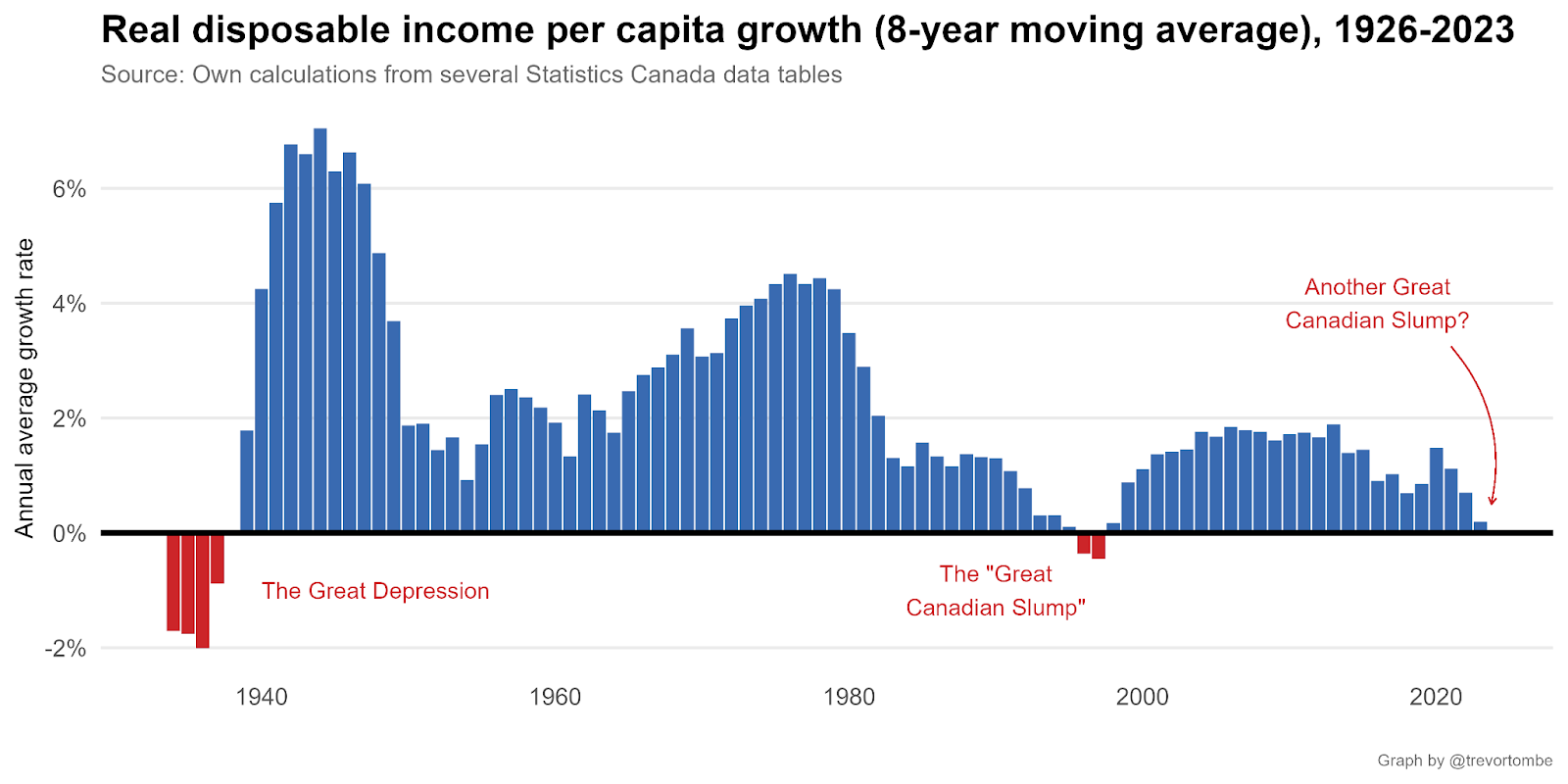

How much our jobs pay—and what’s left after taxes and inflation to buy the items we need—affects us daily. And, unfortunately, income growth has stalled to rates rarely seen in Canadian history. Only twice in the past century have we lived through more sluggish growth than today—both during serious recessions.

Let’s start with pay.

University of Waterloo economist Mikal Skuterud recently estimated that earnings growth has been flat for many years. After adjusting for inflation, he finds average weekly earnings have increased only 1.6 percent between January 2015 and January 2024, or less than 0.2 percent per year.

This isn’t because Canadians are working fewer hours or taking pay in other forms (say, with improved benefits). We see this in a broader measure of total hourly labour compensation. Since the end of 2015, total compensation per hour (adjusted for inflation) has grown by only 1.9 percent. That’s 1.9 percent over the entire period from 2015 (Q1) to 2023 (Q4), which works out to 0.2 percent per year, just as Mikal found for weekly earnings.

And, as I illustrate below, it’s a massive drop from a growth rate of more than 1.5 percent per year that Canadian workers saw over the previous two decades. It’s also clear here why productivity matters: it drives growth in our earnings.

This slow growth is not only below Canada’s own recent past but also below what U.S. workers are seeing. Their average annual growth since 2015 has been 1 percent. Had Canada kept up, we’d earn 6 percent more today—nearly enough to cover higher prices.

Over a longer span of time, the situation is even more alarming. But to make that comparison, a broader measure is needed: real disposable income per person, which is available for nearly 100 years.

This measures the money you have left after taxes, adjusted for inflation. It’s what you can spend or save and is important because it directly reflects living standards. If real disposable income goes up, we can buy more goods or services than before.

Since 2015, I find real disposable incomes have increased in Canada by only 0.2 percent on average per year—the same concerning story as with earnings and labour compensation. The historical context here should raise alarm bells: only during the 1990s recession and the Great Depression has growth been lower.

The Depression is obviously in a class of its own. But the 1990s recession is noteworthy. The economy contracted significantly starting in early 1990, and sustained growth did not return until 1997. It was a massive, long-lasting recession.

At the time, Pierre Fortin (a leading Canadian economist) called it the Great Canadian Slump. In his 1996 Presidential Address to the Canadian Economics Association, he said economic loss “exceed[ed] everything we have known since the Great Depression of the 1930s” and was “second to none in the postwar period.”

By the end of 2023, we were close to repeating that experience, but for different reasons.

It’s not because of inflation. We had faster disposable income growth in the 1970s and 1980s, for example, when inflation was higher for longer. It’s also not because of significant job losses. We are not in a recession, unlike in the early 1990s.

Today, it all comes down to our lagging productivity. Because each hour worked yields little more than it used to, real incomes have stagnated.

There are plenty of culprits. In part, it’s a consequence of oil prices dropping in 2015 and 2016. But that’s not the only factor. Lower business investment, higher policy uncertainty, lower tax competitiveness, pandemic disruptions and aftershocks, unsustainable housing cost increases, a lack of competition and dynamism in key sectors, and more, may all contribute.

Monetary policy may also matter. Pierre Fortin blamed the Bank of Canada for the Slump in the 1990s. Although others, including the Bank’s now-governor, Tiff Macklem, disagreed. Today, keeping interest rates higher for longer than necessary comes with risks for 2024 and beyond.

Whatever the cause of our languishing real income growth, and however difficult it may be to turn things around, governments should acknowledge the issue and try to tackle it head-on. For the most part, they are doing neither.

The “Great Canadian Slump” is back. How long it lasts is up to us.