The latest federal budget did little to address Canada’s mounting productivity challenge. Instead, the government focused on measures that, it argues, will increase “generational fairness.”

One such move sparked considerable debate: increasing capital gains taxes.

This is an important debate to be had, to be sure, but there are other tax changes coming that have been completely lost in the shuffle.

A significant increase in taxes on new business investment throughout the Canadian economy is most concerning of all.

It is likely the largest tax increase you’ve never heard of. And it will lower investment and productivity at a time when we need more of both.

So what is this tax change? And why does it matter?

It all comes down to how quickly companies can write off capital investments, and to the 2018 corporate tax changes that are now gradually being phased out.

The Trump tax cuts

In 2017, the U.S. implemented significant tax reform. Among many other changes, they lowered their corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent and allowed companies to immediately deduct the full cost of certain capital investments. A company spending $1 million on new equipment could “expense” the full amount immediately, lowering its taxable income and tax bill.

Before the change, the company would write off this investment over years. And since a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, accelerating the write-offs is essentially a tax cut.

To understand the impact of these changes, consider one particularly useful measure: the “marginal effective tax rate” on investment, or METR for short. If a project delivers a 10 percent return before taxes but leaves only 5 percent for the investor after all taxes are paid, then the effective tax rate is 50 percent—taxes consume half of the investment’s returns.

Using this measure, the U.S. changes lowered their METR by roughly 11 percentage points—from 29.8 percent to 18.7 percent. That’s an enormous tax reduction.

Serious analysis suggests this could boost the U.S. economy by 1.7 percent, increase wages by 1.5 percent, and increase the total capital stock by 4.8 percent, mainly due to increased investment levels.

Canada’s (temporary) response

Fearing a loss of competitiveness, Canada followed in 2018 by also lowering taxes on new investments—not through tax rate reductions, but by allowing faster write-offs.

But here’s the catch: these changes were temporary.Many of the U.S. tax changes were also temporary. But the negative effect of Canada increasing its tax on investment exists regardless of what the U.S. does.

Starting in 2024, they are gradually being phased out and will be fully eliminated after 2027. The incentive to invest in Canada will consequently fall.

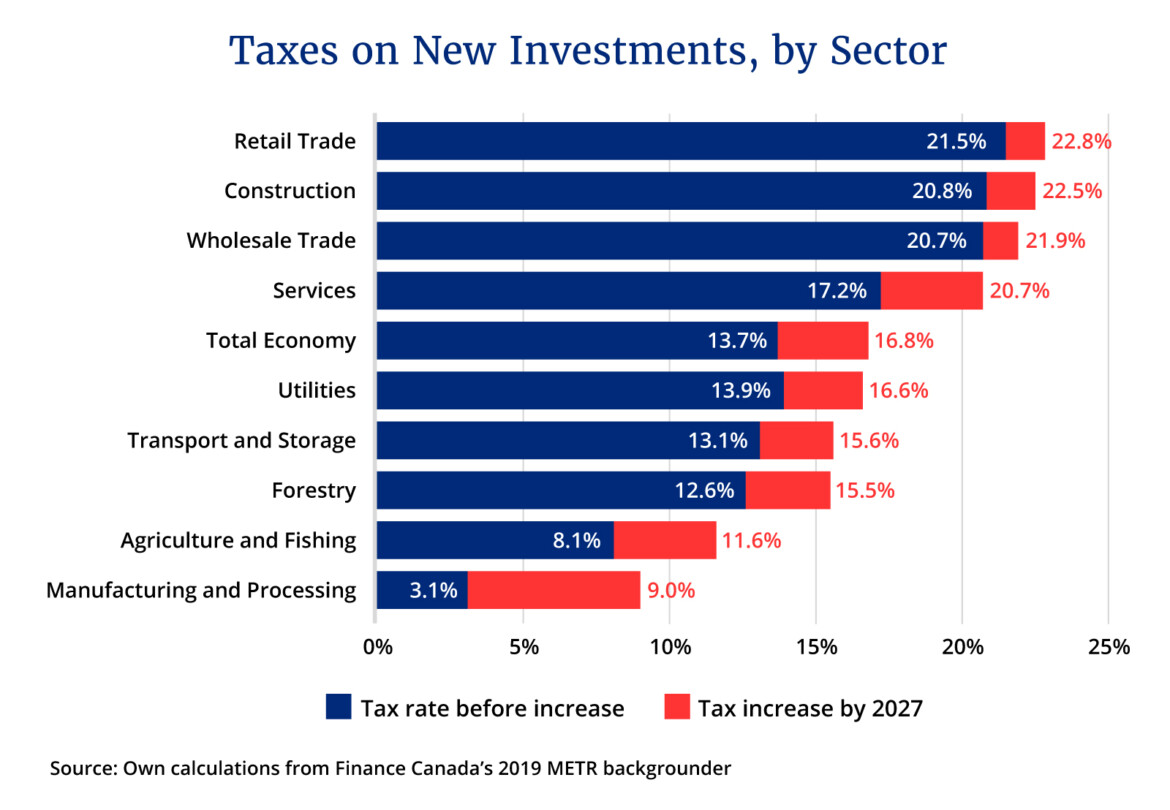

Overall, the effective tax rate placed on new investment in Canada is set to increase from 13.7 percent to nearly 17 percent.

Certain types of investment will see even larger increases. The tax on machinery and equipment investment—a critical source of labour productivity growth—will see an increase from 5.7 percent to 14.2 percent! And there are differences across sectors, as I illustrate below.

The effective tax rate in agriculture will increase from 8.1 percent to 11.6 percent, in construction from 20.8 percent to 22.5 percent, and in services from 17.2 percent to 20.7 percent. The largest increase of all is in manufacturing, which will see the tax on its investments nearly triple from 3.1 percent to 9 percent.

The consequence: smaller investment returns and, therefore, less investment and capital for Canadian workers and businesses.

It’s tough to say by how much, but the generic point is not controversial. By reducing the returns received by an investor, fewer investments will be made. There is considerable evidence for this. Some estimates suggest that, roughly speaking, a 1 percent increase in the METR may lower investment by as much as 1 percent or more.

Higher taxes on investment lowers productivity growth

This is crucial for productivity growth since capital accumulation has historically driven growth.

In a recently published paper for the Canadian Tax Journal and Finances of the Nation, researchers from the Centre for the Study of Living Standards, Andrew Sharpe and Tim Sargent, document that since 2000, approximately 90 percent of all labour productivity gains were from more capital available per worker.

Any serious attempt to boost Canadian labour productivity must improve business investment incentives. Unfortunately, the coming federal tax changes will do precisely the opposite.

Rather than reversing the 2018 tax changes, governments could enlarge them.

Look back at the graph above. Even the lower tax rates on investment in construction and trade are over 20 percent, and services are nearly as high.

We should adopt even more aggressive and expansive measures to lower those rates, as we’ve done for manufacturing. Provinces too can help, with changes to both corporate taxes (where provinces operate their own) and sales taxes. British Columbia and Saskatchewan, for example, levy sales taxes on firm input purchases, which also lowers returns on investment.

Given Canada’s dismal growth in living standards and real incomes recently, getting the tax system right is critical. The budget has led many to focus on capital gains. But we shouldn’t narrowly focus on just one tax change or another; the whole system of raising public funds in Canada needs a good, hard look.

Recommended for You

Letter to a minister: What the federal government should—and shouldn’t—do to solve the housing crisis

Canadians must open their eyes to our growing culture of corruption

‘Albertans do not believe Canada works’: Rick Bell on whether the pipeline deal hurt Alberta separatism

Seven Canadian provinces rank below all 50 U.S. states for economic freedom of residents: Study