It isn’t destiny that brought Mark Carney to power.

The Harvard-trained former Goldman Sachs banker—and now Canada’s prime minister—has worked hard to cultivate the image of “the right man for the moment,” as the country faces economic uncertainty and threats to its sovereignty from Donald Trump.

It’s a politically useful narrative—and one where Carney holds a clear edge over his main rival, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre. And fair enough: he’s helped manage crises before, from the 2008 financial meltdown to the market turmoil around Brexit. But the saviour-in-a-storm trope is ultimately unsatisfying—a partial rendering of how Carney might actually govern.

There’s been nothing random or fateful about his ascent to the top job. If, as Seneca put it, luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity, Carney has been preparing for this moment for a long time. And far from settling for the legacy of a fixer, he harbours a deeper ambition for long-term transformation. He won’t just manage the system—he’ll try to reshape it.

The indispensable Mark Carney

While not quite Seneca, Carney has been known to share another bit of wisdom over the years: buy the cheapest house in the most expensive neighbourhood.

It’s a banal real estate maxim, but a tidy metaphor for his rise. Find your way into elite policy circles. Make yourself indispensable. Climb from the periphery to the centre.That climb began with the cheapest seat at the G7 table—sherpa to Bank of Canada governor David Dodge—and now, should he win the April 28 vote, he’ll be sitting at the head as chair of the upcoming G7 summit in Kananaskis.

Carney’s career—which I’ve followed since first meeting him in 2005—has been a steady, strategic ascent into the upper echelons of global economic policymaking. He’s earned the trust of powerful figures as consigliere, parlaying one role into the next—always upwards, never sideways.

The trajectory has been remarkable. Harvard and Oxford. Goldman Sachs. In 2003, he applied for a deputy governor role at the Bank of Canada and got it by impressing then-governor David Dodge in a one-on-one interview. That role gave him proximity to the most important global economic forums—though still very junior.

His elevation came in 2004, when then-Finance Minister Ralph Goodale brought him into government as a senior aide. Carney continued his sherpa duties but also helped shape the Liberals’ economic agenda, including pre-election tax cut messaging.

His close rapport with Goodale didn’t hurt him when Stephen Harper’s Conservatives took power in 2006. Carney quickly earned the trust of Jim Flaherty, the new Finance minister. I remember spotting him beside Flaherty on a flight to Moscow just days after Flaherty’s appointment—en route to a G8 meeting. Before Flaherty had staff, he had Carney.

Their bond was strong. Flaherty would lean heavily on Carney, eventually naming him governor of the Bank of Canada—a surprise to many, who expected the job to go to the bank’s number two, Paul Jenkins. But Carney was helping Flaherty resolve a mini-crisis in Canadian money markets in 2007, and as the global financial system was beginning to teeter, he turned to his trusted aide.

The night the appointment was announced—October 4, 2007—I ran into Flaherty at a popular Ottawa bar. He said: “I got my man.”

Becoming governor was a significant promotion. It placed Carney at the G7 table just as the global economy was going off the rails, and quickly made him a key player in the international response.

Canada’s relatively smooth ride through the crisis boosted his influence in global policy circles. With Flaherty’s backing, G20 leaders tapped him to lead the Financial Stability Board—a prestigious global body charged with post-crisis banking reform.

But back home, things with Flaherty began to fray. Carney’s growing public profile—stretching well beyond a central banker’s traditional remit—raised eyebrows. The final break came in 2012 when it was revealed that Carney had spent part of his summer at the Nova Scotia home of Liberal MP Scott Brison, then the Finance critic. It was implied, though never made explicit, that discussions included him running as Liberal leader. Flaherty later told me he felt betrayed.

(One Conservative deadpanned to me that they’d always assumed Carney was a Tory because he has four kids.)

Had he stayed in Ottawa, his political entanglements would have created a dilemma for Flaherty, who may have even forced him out.

Prime Minister Mark Carney meets with British Prime Minister Keir Starmer as he arrives in London on Monday, March 17, 2025. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

London calling

But behind the scenes, a new opportunity was emerging. U.K. Chancellor George Osborne wanted him to run the Bank of England and help overhaul British banking in the wake of the crash.

Carney accepted, cutting short his Canadian term and solving the political problem neatly. While in London, he developed what seemed a sudden—and very active—interest in climate change. That focus would define the next chapter of his career. After stepping down from the Bank of England in 2020, he became a leading figure in finance-led climate initiatives, eventually taking on the role of UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance.

He also joined the boards of Brookfield Asset Management, Bloomberg, and Stripe—major players in finance and tech. His Rolodex expanded. So did his influence.

But Carney never drifted far from Liberal orbit. He stayed close with Trudeau-world figures like Gerry Butts. The overlap between his and the former PM’s teams became so obvious that rival Liberal camps dubbed his leadership effort “Team Do-Over.”

Politics is a different game

Carney has built a career convincing powerful people that he’s indispensable—using a blend of intellect, communication skills, an innate charm (helped by George Clooney-good looks), and unmistakable ambition.

The list of people who’ve sought his advice is impressive: Dodge, Goodale, Flaherty, Harper, Osborne, Cameron, Johnson, Guterres, Flatt, Bloomberg. And many more, no doubt.

But being prime minister is a different beast. Intelligence, charm, and economic credentials are not sufficient.

As Chrystia Freeland quipped during the Liberal leadership race, people like Carney are hireable. Up until now, his career has borne that out. But being a great consigliere doesn’t guarantee you’ll make a great boss.

The coming campaign will tell whether Carney has the political chops to be electable—the coalition-building instincts, the retail touch, the stamina under fire, the ability to withstand intense public scrutiny. The big risk for Carney will be how to navigate public opinion when democratic skepticism eventually kicks in; Canadians won’t buy forever the “trust me, I know best” pitch. And if Canada really is facing an existential threat, it seems the real test of Canada’s next leader will be who can inspire and unite the nation, rather than who’s most adept at moving economic levers.

But there are others better than me at political analysis. What I can offer are a few observations, drawn from his career and worldview, on how he sees the role of government—and the challenges his approach will face should he get voted into power.

Is Carney made for the moment?

There is a type.

Carney belongs to a global elite of economic policymakers—Christine Lagarde, Mario Draghi, and the like—who share a mindset: technocratic, regulatory, hands-on.

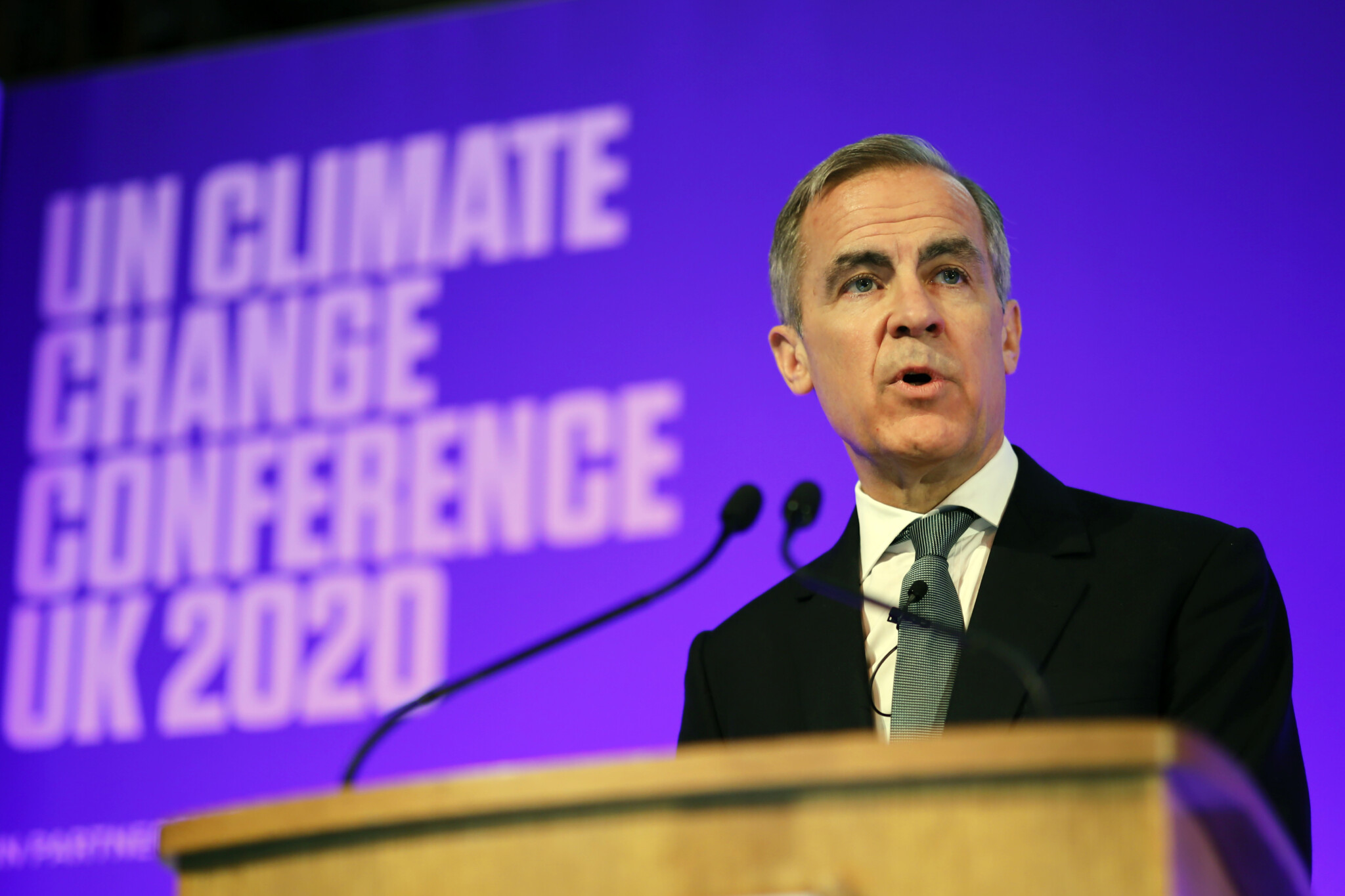

Outgoing Bank of England governor Mark Carney, and COP26 Finance Adviser to Britain’s Prime Minister, makes a speech at the 2020 United Nations Climate Change Conference COP26 at Guildhall in London, Thursday Feb. 27, 2020. Tolga Akmen/Pool Photo via AP.

They’re not driven by money—they could make more in the private sector. What drives them is a shared belief that their vision and expertise make them uniquely suited to lead.

They don’t just play the game. They set the rules.

They respect markets—and generate much of their legitimacy from being able to understand them—but they mistrust them too. Carney’s “tragedy of the horizon” concept highlights the short-termism of markets and the need for state intervention to address long-term challenges like climate change.

This isn’t Trudeau-style excess or heavy-handed statism. But make no mistake—they believe in steering. And they see crises as opportunities for agenda-setting.

Carney wants to be seen not just as a steady hand but as the architect of Canadian economic transformation. And he is more or less saying as much.“I know we need change, big change, positive change,” Carney said in a speech kicking off his federal election campaign.

So, his instincts will be interventionist. He’ll centralize power as much as any recent Canadian prime minister. As a manager, he can be hard on staff—with the intensity of the Eye of Sauron—but he raises the bar everywhere he goes and gets the most out of the people who choose to work for him. He won’t rely on folks he doesn’t trust and will bypass poor performers or obstructive processes.

Being a partisan free agent, he’s less likely to be constrained by Liberal legacy concerns. He probably won’t worry too much about how unpopular decisions could impact the party’s future.

Even though he’s adopting some traditionally Conservative ideas—fiscal discipline, tax competitiveness, resource advocacy—his approach will be fundamentally different from Poilievre’s: more hands-on, strategy-oriented, and state-driven.

Global coordination will be a hallmark. He’s a full-throated globalist: global challenges like climate demand globally coordinated responses. It’s been central to every major initiative he’s led—from post-crisis banking reform to the Net-Zero Banking Alliance. His immediate instinct to rally European allies in response to Trump’s belligerence is no surprise.

And he will make mistakes, as everyone does.

Miscalculation—or perhaps overshooting—is always a risk for supremely confident people with strong track records. While Liberals are selling Carney as an untouchable global success story, even in his areas of expertise, the record is not unblemished.

Carney’s tenure at the Bank of England drew criticism for overreach, mixed results, and communication missteps. He was accused of hyping crises and pushing pet projects.

But what is undeniable is that whatever happens in this election, Canadians face a stark choice.

Poilievre rejects elite-driven globalism outright. He casts Carney as the ultimate gatekeeper—the very type he’s built his movement against. His message is about unleashing markets, cutting bureaucracy, letting Canadians get ahead.

It’s free-market orthodoxy.

Carney’s model is economic statecraft: a more command-style approach, rooted in planning and regulation.

Some might argue that’s what the moment demands. In a world of economic warfare and geopolitical flux, centralization and planning may feel reassuring.

But others will argue this is no time for technocratic idealism. Planning assumes cooperation—which could be a stretch in today’s fractured, zero-sum world. Carney’s struggles to hold together the UN-backed Net-Zero Banking Alliance are already a warning sign.

And in a country grappling with low investment, overregulation, and climate transition fatigue, it’s not obvious that more rules and more climate ambition are the answer.

Sometimes, we get so busy planning that we forget to adapt. Or as John Lennon put it: “Life is what happens while you’re busy making other plans.”

Travel expenses for The Hub’s election coverage are made possible by the Public Policy Forum, the Rideau Hall Foundation’s Covering Canada: Election 2025 Fund, and the Michener Awards Foundation.