Ottawa likes to tell itself a reassuring story: Canada is the sober borrower of the G7. In particular, we have smaller deficits, a lower debt-to-GDP ratio, and a central bank more disciplined than its U.S. counterpart. That narrative, which has become gospel among federal policymakers, is used to justify spending and resist comparisons to America’s fiscal picture. But the bond market is starting to tell a different—and far more sobering—story.

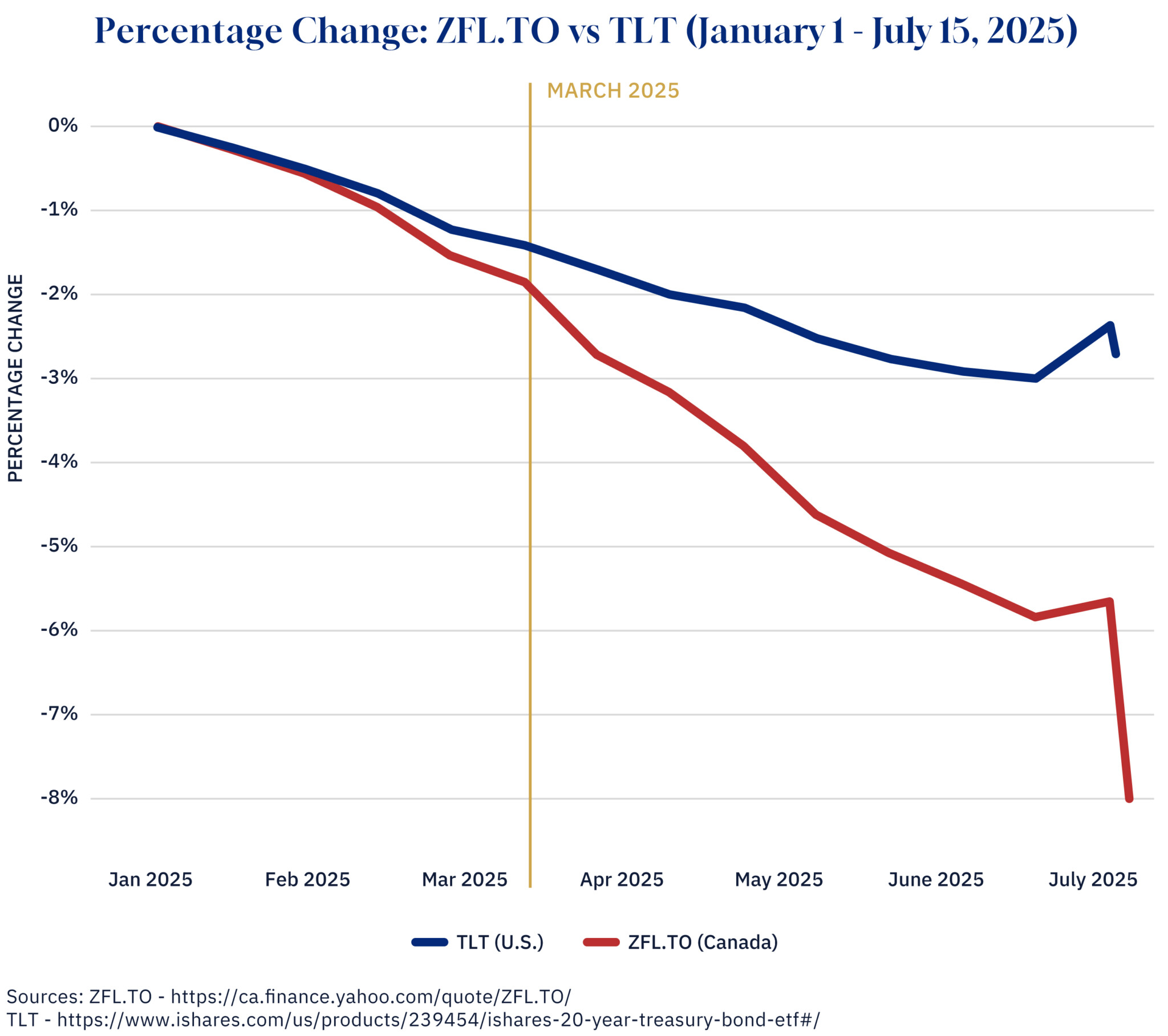

As of trading today at noon, two bond ETFs (Exchange-Traded Funds) that track long-duration U.S. and Canadian government debt help illustrate what’s going on. In the United States, the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT) is $85.05 US, down 2.85 percent from its price on January 2. In Canada, the Bank of Montreal Long Federal Bond Index ETF (ZFL.TO), which tracks federal government bonds with longer durations, sits at $11.87 CA, down approximately 8.75 percent since the start of the year (see chart 1). And, while the two funds are not identical in terms of the bonds they hold, both portfolios have very similar duration and maturity.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

This isn’t just a quirk of ETF pricing. Bond ETFs are sensitive indicators of market sentiment around borrowing costs. When the prices of long-bond ETFs fall, it means yields—i.e. the cost to borrow over the long term—are rising. The fact that ZFL.TO has declined more than twice as much as TLT this year is a clear signal: Canadian long-term borrowing costs are rising faster than those in the U.S.

This divergence is all the more remarkable because it contradicts the story our political leaders have been telling. The Bank of Canada’s orthodoxy, our triple-A credit rating, and the government’s cautious framing of deficits were supposed to reassure markets that we were the safer bet. But if that were true, why is Canadian long-term debt underperforming its U.S. counterpart?

The answer isn’t just technical. It cuts to the core of how markets judge sovereign risk. And increasingly, they’re no longer judging Canada by its past reputation but by its present trajectory.

The belief that Canada enjoys a permanent borrowing advantage over the U.S. has become untethered from bond market reality. Instead of congratulating themselves on fiscal prudence, policymakers should be asking why the country’s long bonds are being punished more than those of a country with a much deeper deficit problem. The U.S. has a federal deficit well north of 5 percent of GDP and a political system repeatedly flirting with shutdowns and debt ceiling crises. Yet its long-term borrowing costs have remained stable, even falling at certain maturities.

Canada, by contrast, has seen its borrowing costs climb. Why?

Because markets are forward-looking. They care less about where your debt-to-GDP ratio stands today than where it’s likely to go in the next five to ten years. And on that front, Canada’s path is increasingly opaque. Federal fiscal plans are littered with new permanent spending, tepid economic growth projections, and few signs of a political appetite to restrain entitlements or scale back transfers. Add in a heavy dependence on consumption taxes and a declining per-capita productivity trend, and the picture becomes more complicated.

Bondholders are reading that picture in real time. They don’t care that the Department of Finance’s talking points say we’re better than the Americans. They care that a country with a comparatively smaller economy, aging population, and less liquid bond market is racking up long-term obligations with no clear growth plan to offset the risk. They also know that Canada lacks the structural advantages of the U.S.—a global reserve currency, unmatched capital markets, and institutional scale, meaning our room for error is far smaller.

In other words, Canada is being repriced.

This repricing has implications that stretch well beyond federal finances. Higher long-term borrowing costs filter through the economy. They raise the cost of financing infrastructure, increase debt servicing burdens for the federal and provincial governments, and put pressure on mortgage rates, which are often tied to long-end bond benchmarks. Pension plans and insurance companies that hold long-term federal debt are also affected, as are businesses that rely on the bond curve to issue debt.

Perhaps most importantly, this shift raises the political cost of continued deficits. For years, the federal government could borrow cheaply and justify new spending by arguing that “interest rates are low.” That era is ending. The nearly 8 percent decline in ZFL.TO since January is evidence that markets no longer see Canadian debt as a low-risk, low-cost proposition.

This isn’t to say Canada is on the brink of a fiscal crisis. But it does suggest that Ottawa needs to reassess its assumptions. The belief that Canada can continue to borrow at a premium—or rather, a discount—relative to the U.S. has become untenable. The market is now questioning that assumption. And for good reason.

The takeaway is clear. If Ottawa wants to preserve Canada’s reputation as a fiscally sound borrower, it needs to stop coasting on its legacy and start responding to what markets are signalling today. That means credible spending restraint, a clearer path to balanced budgets, and a growth agenda that doesn’t depend entirely on population increases to mask declining productivity.

If Canada is being charged a higher premium to borrow than the United States over the long term, it suggests that something fundamental has changed. And the longer policymakers pretend otherwise, the worse that premium could become.

Generative AI assisted in the creation of this article.