In May 2021, a headline from the CBC gripped the country: “Remains of 215 children found buried at former B.C. residential school, First Nation says.”

The story went global, sparking vigils, the lowering of flags, arson attacks on churches, and $200 million in survivor-focused funding. It helped cement the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and even prompted an apology from Pope Francis.

But the claim that remains had been “found” was quickly clarified. Ground-penetrating radar at the Kamloops Indian Residential School site had identified soil disturbances consistent with the shape of graves, but not confirmed human remains. Excavation has never taken place. The Nation has not authorized it, citing cultural protocols and community priorities.

Four years on, a recent Angus Reid Institute survey found most Canadians sympathetic to survivors and their families. Nearly 70 percent say residential schools were a form of cultural genocide, and 54 percent say Canada must continue to address their legacy.

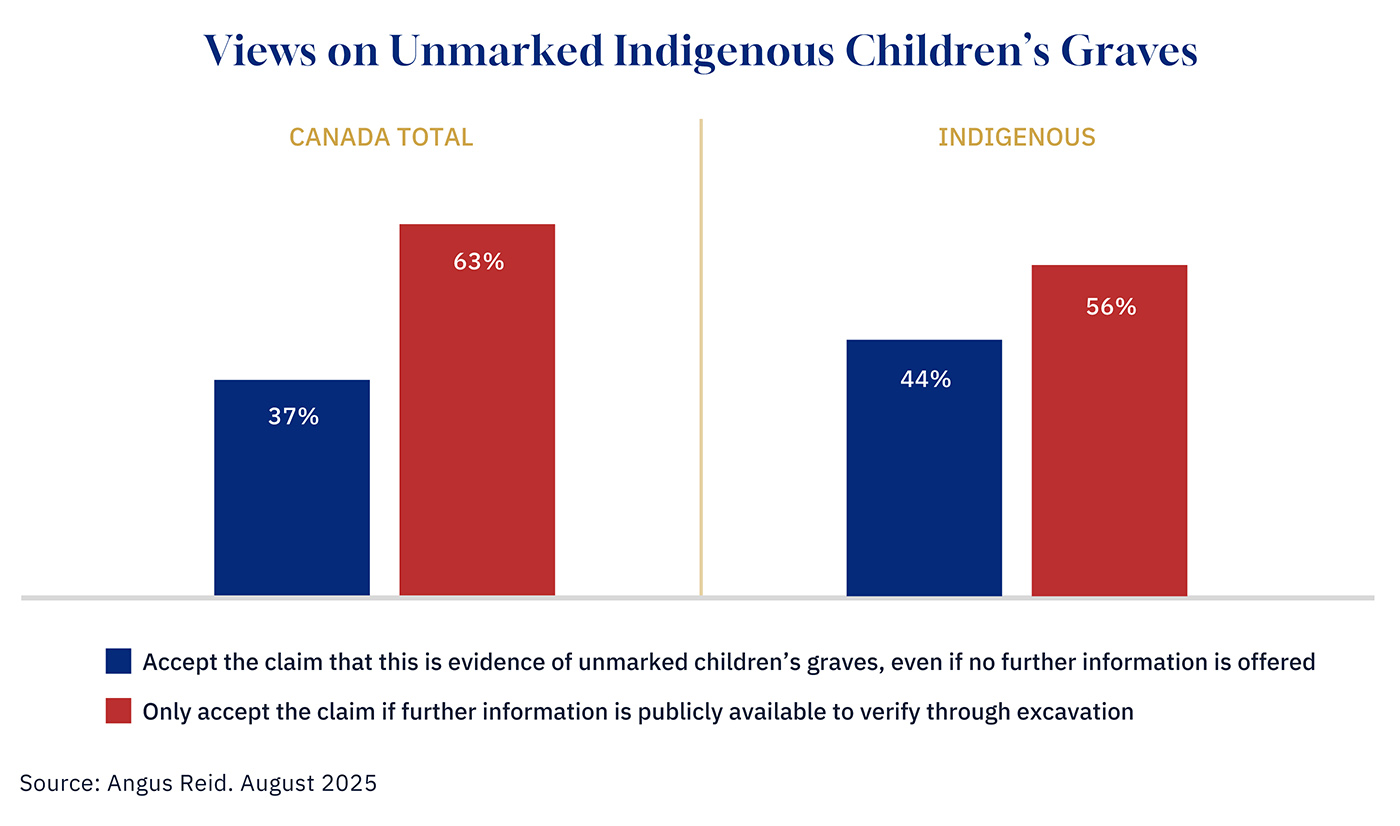

Yet a clear majority—63 percent of Canadians and 56 percent of Indigenous respondents—say more evidence is needed before accepting that the anomalies at Kamloops are children’s remains.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

As a First Nations chief whose own family has lived the intergenerational harms of residential schools, I believe reconciliation demands two things in equal measure: first, an unflinching recognition of the historical truth that thousands of Indigenous children suffered and died in these institutions; and second, a commitment to transparent, evidence-based public claims about potential graves. The controversy over the claims of graves in Kamloops clearly invokes the second point, but it shouldn’t detract from the first.

Whether or not there are unmarked graves in this particular instance doesn’t change that Indigenous children faced violence or died at residential schools. That’s already a historical fact. The whole story in Kamloops has, in that sense, become a distraction for activists on both sides of the issue.

For most Canadians—namely those among the majority who believe that we must address the legacy of residential schools and follow the evidence—the risk of suppressing questions or avoiding nuance is that it creates skepticism, fuels accusations of a moral panic, and ultimately undermines confidence in the reconciliation project itself.

On the other hand, ignoring survivor testimony and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)’s findings trivializes deep intergenerational trauma.

Canada must learn to hold both truths at once—insisting on accuracy without diminishing the lived experiences that make this history impossible to dismiss.

The history shaping the debate

Residential schools operated in Canada from the 1880s until the last of them closed in 1996. More than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children were taken from their families and forbidden from speaking their languages or practicing their cultures.

Warnings about poor conditions in the schools were raised throughout their history. In 1907, Dr. Peter Bryce, Canada’s chief medical officer, reported mortality rates as high as 40 percent in some institutions, citing tuberculosis, overcrowding, and poor sanitation. In 1922, Bryce published The Story of a National Crime, accusing the Department of Indian Affairs of “criminal negligence.” Similar investigations in 1935 by the United Church and in the 1960s by anthropologist Harry Hawthorn documented underfunding, neglect, and poor educational outcomes. Any reforms that did occur were slow and piecemeal.

For many Indigenous people, the radar findings in Kamloops align with accounts of negligence causing death. For critics, the lack of excavation leaves the claims unproven.

Yet, irrespective of what was found (or not found) in Kamloops, the TRC documented at least 3,200 deaths at residential schools, often from tuberculosis, malnutrition, and neglect, while noting the real number is likely far higher. “Volume 4: Missing Children and Unmarked Burials” found that many death records were never created, others were incomplete, and some were destroyed entirely. This lack of documentation has left the National Student Death Register far from complete. It’s also notable that Kamloops itself was the site of a criminal case in the 1990s involving former residential school employee Gerald Moran, who in 2004 was convicted on 12 counts of indecent assault for crimes committed at the school and sentenced to three years in prison. The same TRC volume recorded harrowing survivor testimony: “One morning, the little boy who slept in the bed next to mine was gone. They told us he was ‘sent home,’ but his parents never saw him again,” said an anonymous survivor.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

What’s at stake

From my perspective as a First Nations Chief, the impending danger stemming from this recent experience is twofold. If mere skepticism is met with censorship, the accusation of being a residential school denier, or the stupidity of criminalizing critics, reconciliation risks becoming performative and brittle.

Meanwhile, if critics ignore the documented harms of residential schools, they alienate Indigenous people and trivialize generational trauma.

My own family’s history—my grandmother’s abuse at St. Mary’s Indian Residential School in B.C., her attempts to cope with the trauma through alcohol, and my mother’s fetal alcohol syndrome—reflects the long shadow of these institutions. These realities are not erased by asking for evidence about specific claims.

We should expect detailed public statements from Indigenous nations about potential graves to be supported by widely available public evidence, and met by a media that respectfully verifies the facts.

At the same time, Canadians skeptical of the Kamloops findings should grapple with survivor testimony and the TRC’s record, which make clear that many children never came home. Based on this Angus Reid polling, that’s exactly where most Canadians appear to be.

Several thousand gathered for a Healing Walk throughout downtown Winnipeg and a Powwow on the National Day for Truth And Reconciliation Thursday, September 30, 2021. John Woods/The Canadian Press.

Bridging the divide

The phrase “Truth and Reconciliation” begins with the word truth for a reason—reconciliation cannot survive selective truth-telling. Suppressing questions breeds mistrust. Downplaying history deepens wounds.

A healthier national conversation requires both transparency and empathy—recognizing the sovereignty of Indigenous nations while understanding that withholding evidence will leave some unconvinced. Canadians are ready for a more nuanced conversation: one that honours survivors’ pain, demands accuracy from media and politicians, and resists the urge to criminalize debate.

The truth about Kamloops may remain unresolved until excavation occurs. But the truth about residential schools—the abuse, the cultural erasure, the thousands of confirmed deaths—has been established beyond a reasonable doubt. If we can hold both facts in mind, we might replace mistrust with understanding and make reconciliation more than just a slogan.

For a deeper dive into the history, the media coverage, and what reconciliation requires today, you can watch my full breakdown here: A Chief Breaks Down the Unmarked Graves Controversy.