Canadian businesses are sometimes accused of being late adopters of new technologies. As the stereotype goes, U.S. companies will boldly jump in with both feet to try something new, while Canadian firms sit back and wait to see how things unfold before dipping their own toes in the water.

Is AI the next example of that trend? It really depends on who you ask.

According to the 2023 Survey of Digital Technology and Internet Use, only about 8 percent of Canadian companies with 10 or more employees say they’re using AI. That puts Canada at a measly 24th of the 28 OECD countries reporting data on the subject.

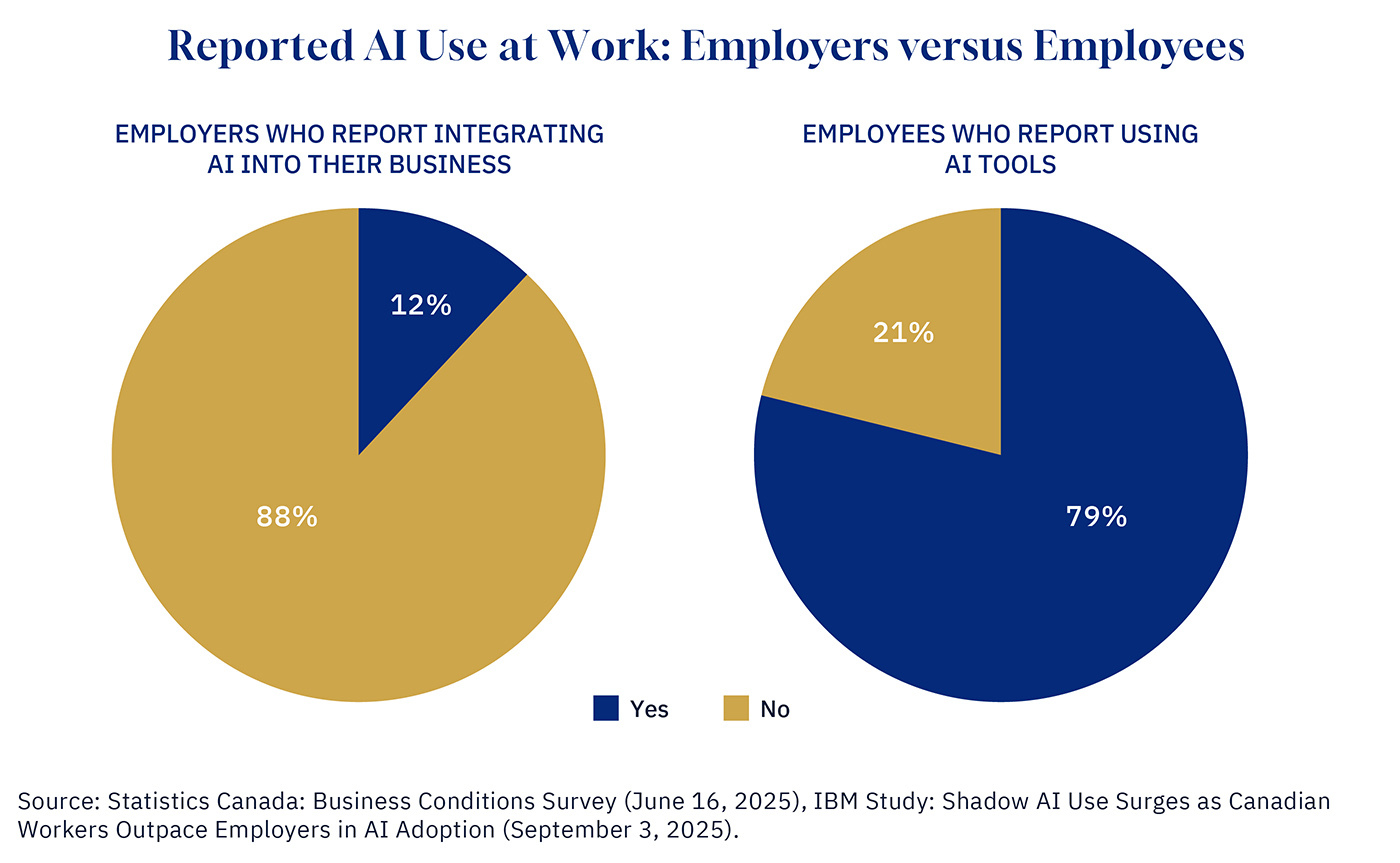

Statistics Canada’s more recent Business Conditions Survey reports a slightly higher, but still low, number. It says that 12 percent of business leaders report AI use in the workplace, with the most common application being text analytics—tools that summarize long meetings or help search for information. But even that is rare, as only 4 percent of businesses report using AI for that purpose.

On the bright side, adoption is on the rise. That 12 percent figure is double what it was just a year earlier.

That said, AI use in the workplace is likely much higher than what employers report. IBM just released a study last week that finds 79 percent of Canadian office workers use AI.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

What explains such an enormous gap between the two survey results?

One reason is the difference between AI tools provided and approved by the company and AI software that anyone can access. That same IBM study found only 25 percent of workers are using approved, company-managed AI platforms—the kind business leaders would count as officially integrated. The rest are turning to tools like ChatGPT or Gemini to draft emails, summarize documents, brainstorm, or even write bits of code.

Another factor is that business leaders may not realize how much AI is actually being used. Research by McKinsey, a consulting firm, found that employees are much more likely to be using AI than their managers expect. For example, while leaders estimated that only 4 percent of employees use generative AI for a significant portion of their daily work, in reality, the share is about three times higher.

Finally, it could come down to a matter of interpretation. Employers may be thinking about integrated AI systems when they respond to surveys, whereas workers might be interpreting questions more literally.

It’s also highly likely that Canadian office workers are under-reporting how much they use AI. About half say they’re hesitant to admit AI use to their managers, worried it’ll make them look lazy, incompetent, or like they’re cheating.

The bottom line is that whether it’s because employees find readily available AI to be more valuable or because workplace rules around AI are unclear, informal AI use is commonplace in the office.

While it’s good that AI use is likely much higher than official statistics suggest, a more formalized approach to AI integration could offer greater benefits. Individual employees may be missing out on ways AI could make their jobs easier, or they could be using it in risky ways that expose sensitive data and accuracy problems.

Unreported AI use is also a problem for companies. If they don’t know if (or how) people are using AI, they can’t set clear policies, provide proper training, avoid risks, or figure out where the biggest productivity gains are hiding.

On a larger scale, it’s a missed opportunity for the Canadian economy. AI is an important component of future productivity growth. With more formal integration into the work world, it could help to close Canada’s productivity gap.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta. To learn more, read the commentary here.