DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Centre for Civic Engagement.

Over the past decade, politics across the Western world has been reshaped by a quiet but decisive upheaval. The familiar stability of postwar party systems, anchored in broad, centre-left and centre-right coalitions, has given way to a more volatile terrain defined by populist insurgencies, fractured identities, and cross-cutting cultural divides. In the United States and Britain, conservatism itself has been remade, no longer bound by the “fusionist” marriage of free-market libertarians and social traditionalists.

Instead, conservative parties abroad have been compelled to choose: lean into economic discontent with policies that depart from neoliberal orthodoxy, or embrace culture-war politics that offer new sources of cohesion at the expense of old allies.

Canada, however, presents a puzzle. At a moment when conservative movements elsewhere are being pulled apart and stitched back together into unfamiliar patterns, Pierre Poilievre’s Conservative Party appears to have held together a coalition that looks strikingly familiar.

The same fusionist formula, skepticism of government, promises of tax relief, and hostility to red tape, remains intact. Social questions are largely reframed as matters of individual liberty rather than national identity. And yet, despite this continuity, the Conservatives have found themselves buoyed by the very real populist discontent that has undone their peers abroad.

How durable is this Canadian exception? Can a coalition built on decades-old rhetoric and orthodox policy commitments remain coherent in a country grappling with stagnation, housing shortages, and declining productivity? And what does the narrow Liberal victory in 2025 tell us about the future of the centre-right?

This DeepDive argues that Canadian conservatism’s unusual resilience reveals as much about Canada’s economic malaise as it does about its political traditions, and that the durability of fusionism may hinge less on ideology than on the hard realities of Canada’s stalled economy.

The Canadian Conservative puzzle

Across much of the West, the familiar architecture of conservative politics has been shaken. The old “fusionist” coalition no longer maps neatly onto voter preferences. Where once economic libertarians and cultural conservatives marched in step under a shared suspicion of government, today those camps are drifting apart. Business-minded conservatives, more cosmopolitan and socially liberal than in the past, increasingly find themselves at odds with working-class voters who lean traditional on cultural questions but demand a more interventionist state to guarantee material security.

This divergence has compelled conservative parties abroad to embark on a period of experimentation. Some have moved to soften their economic orthodoxy, embracing tariffs, industrial policy, and selective expansions of the welfare state. Others have leaned into cultural debates, from immigration and identity to family policy and national sovereignty, seeking to build cohesion through appeals to belonging and social order.

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre greets supporters during a campaign stop at a bar in Fredericton, N.B., on Monday, March 31, 2025. Stephen MacGillivray/The Canadian Press.

Yet both strategies expose risks: the first by straining ties with business constituencies still invested in economic liberalism, the second by alienating socially progressive or libertarian conservatives whose economics remain right-of-centre.

The United States and the United Kingdom illustrate this dynamic most clearly. Republicans under Donald Trump and, more recently, the Reform Party in Britain have stitched together coalitions skewed toward working-class voters, blending sharp cultural appeals with an eclectic economic agenda that mixes protectionism with familiar tax-cutting rhetoric. The results have been electorally potent, but also fragile, resting on an uneasy balance between constituencies that do not share the same vision of the good society.

While these adjustments have preoccupied conservative attention elsewhere, they do not seem to have arrived in Canada. Instead, the Poilievre Conservatives have retained a considerable degree of success and cohesion on the basis of a genuinely felt conventional fusionist program.

As in the past, rhetoric remains directed towards bureaucratic inefficiency, excessive government spending, and economic overregulation (e.g., the “gatekeepers”). And, when engaged, cultural or social issues are framed as a matter of individual freedom; topics with starker implications—abortion, same-sex marriage, minority rights—are avoided when possible.

A large part of this divergence is driven by the unique impact of Poilievre’s leadership of the party. One is tempted here to mention the common (though always exaggerated) refrain among analysts that the electoral map forces Canadian Conservatives to take more moderate positions than their global peers. In fact, the party appears in 2025 to have reaped the fruits of the populist realignment—winning the support of new constituencies—without the needed programmatic adjustments or trade-offs.

And yet, the sheer universality and impact of these changes elsewhere cannot be overlooked, suggesting that something more structural may be at work in maintaining this Canadian divergence. This is because, even while populist insurgencies are the leading proximate causes of the realignment, they are ultimately the consequence of the much deeper transformations that have been reshaping Western societies over the last several decades, whether linked to knowledge capitalism, globalization, or post-materialist cultural conflicts. Regardless of their relationship to political parties, Canadians are being shaped by the same tensions around class, education, age, gender, religiosity, and values that are transforming political competition elsewhere.

Continuity or change in the Conservative coalition?

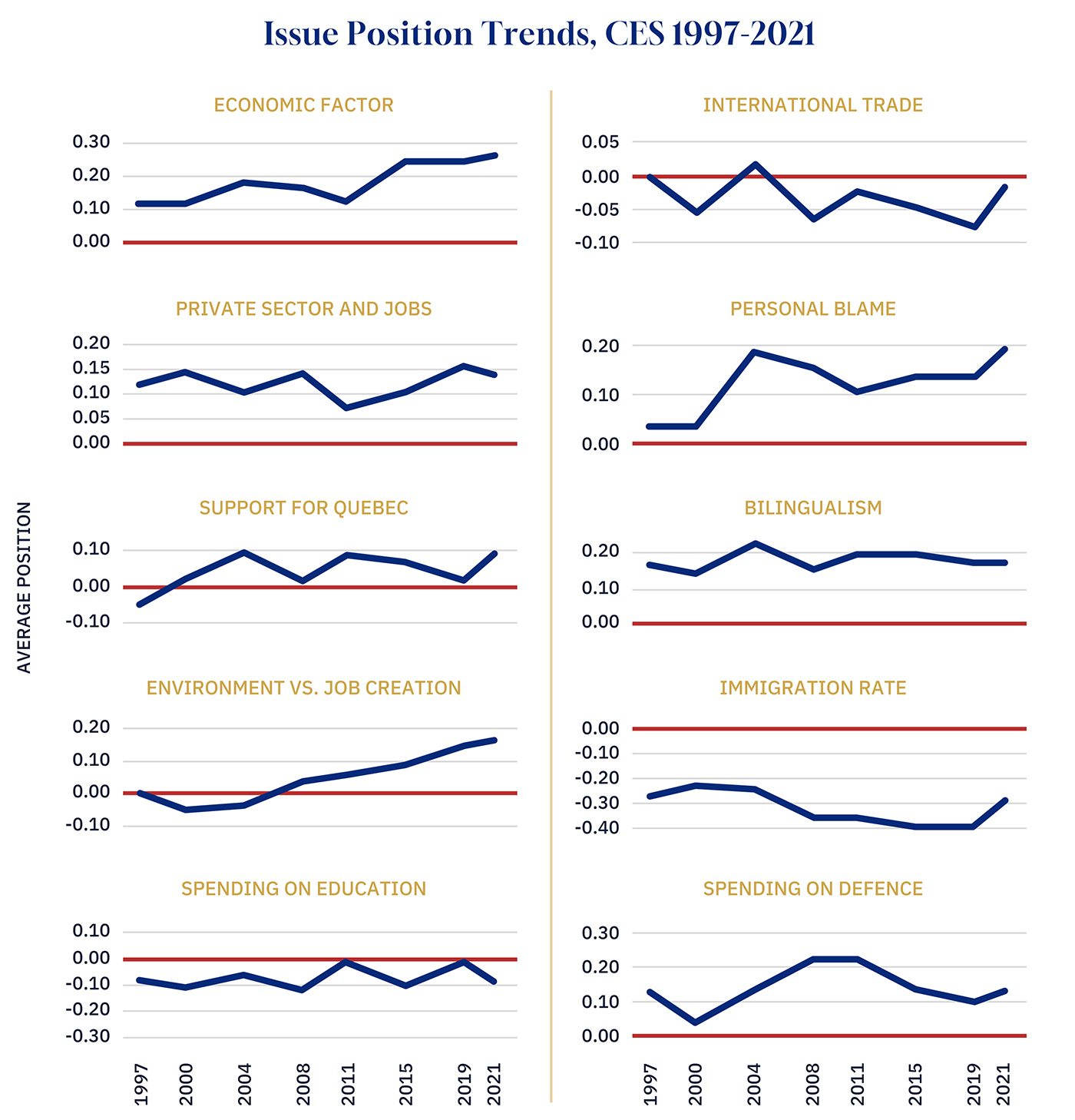

Using the Canadian Election Study between 1997 and 2021 (excluding 2006, and 2025 is not yet available), I collected data on the Canadian electoral marketplace, assessing the relationship between policy positions, demographic factors, and vote choice. I was interested in seeing (as has been the case in other countries) whether the relationship between conventional “right-wing” economic and social positions has also come apart in Canada.

The graph below charts the relationship between cultural traditionalism and several issue positions for all voters. The y-axis charts the strength and direction of the relationship, while the x-axis traces it over time across the datasets. While a point above the red line indicates a positive relationship (being socially traditionalist makes one very likely to support private sector-led job creation, for example), a point below indicates a negative one (social traditionalism is associated with opposition to a high immigration rate, for instance).

As can be seen below, what I found is quite striking. The overriding impression we have here is one of continuity within the conservative electoral coalition itself—one that shows very little change since the Reform era. In Canada, voters with more traditionalist social and liberal economic attitudes are still very likely to be the same people, exhibiting little cross-sectional tension. The sort of bundle of issue positions that shape what we once associated with a typically centre-right policy orientation—combining economic liberalization, social traditionalism, greater defensive spending, and immigration skepticism—still has broad popular appeal. The only exception to this continuity—where social traditionalists are more likely to say that they prioritize job creation over environmental protection when the two conflict—seems consistent with this interpretation.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

These attitudes, moreover, remain associated with the same demographic characteristics and party identification. That is to say that economic and cultural conservatives are not only the same people, but that they are still likely to be older, more religious, male, and less university educated. Each attitude also has a strong and consistent impact on vote choice: While social traditionalists and economic liberals support the conservatives, those with more socially progressive and economically interventionist attitudes remain divided between the NDP and the Liberals.

Fusionism, it would seem, persists in Canada. Not only is support for the party predicated on a general support for economic liberalization, but social traditionalists continue to show a genuine preference for limited state capacity. This entails that, unlike the emergent cultural and economic tensions that have unraveled centre-right coalitions elsewhere, Canadian conservatism has retained a fusionist base, structured around the sort of programmatic commitments and rhetorical cliches that conservatives have been promoting for the last three decades: a core economic and fiscal strategy that appeals across cultural and social divides.

Conservatism in the 2025 election

What accounts for this divergence with other conservative parties? And, just as importantly, does it still accurately describe post-2025 conditions? Unfortunately, I currently lack access to data that would allow for direct comparisons between now and 2021. I can, however, interpret the results of the 2025 election, along with what they may mean for Canadian conservatives in the long term, in light of the findings above.

As mentioned, the 2025 Conservative campaign generally consisted of the sort of programmatic commitments and rhetorical allusions that centre-right parties have, more or less, been voicing for the last several decades. Even the populist vibe of it is, despite commentariat vigilance, not all that new. Academics and analysts used the exact kind of language to describe Reform and the Harper-era iteration of the CPC.

Regardless of the main electoral outcome, the simple fact that the party had been able to amass considerable public momentum and the support of more than 40 percent of Canadians on the basis of this strategy means that there is still something to it. It’s an approach that not only still resonates, but one that can draw together a diverse group of voters into a reasonably unified centre-right coalition.

An initial line of interpretation to make sense of this could be to reemphasize the unique ideological characteristics of Canadian Conservatism. One could argue, for instance, that the coalition’s long-established identity as a challenger to Central Canadian elites makes members inherently adverse to a large federal government.

But this approach is wrong on two accounts. The first is that the more establishmentarian and “Tory Touched” nature also attributed to Canadian conservatism would, in contrast, predict that Canadians are even more sympathetic to a program that emphasizes a positive national identity and state-directed economic activity.

Second, and more importantly, this is too abstract. For while we can endlessly discuss what “conservatism” really is, your average person doesn’t reflect on their political opinions with an eye to conceptual consistency. The shape of one’s political engagement is more often a consequence of the interaction of one’s deeply held values and life experiences with the actual problems they face.

Instead, the robustness of the Canadian conservative identity is a reflection of Canada’s particular economic challenges.

In the United States, most of the working-class populism reshaping the centre-right is about where the state had been absent. That is, it has been a consequence of how the political establishment’s embrace and depoliticization of global free markets, while producing prosperity for many, actively displaced and hurt large swaths of Americans.

The impulse of Trumpism, therefore, has been—regardless of the more economic or cultural connotations of any given issue—to use state power to produce more desirable social ends and re-politicize policy areas once left to technocrats and market forces. It exposes sharp and cross-cutting voter differences in both social vision and economic interest.

But this isn’t Canada’s problem. Canadians have not suffered from the adverse consequences of runaway economic displacement as much as we have collectively all hit the wall of stagnation—the aptly labelled “lost decade.”

Here, populist discontent has been about where the Canadian government is too active. The fact that, for all our challenges, too much of our political, economic, and cultural establishment are insular and parochial in their outlook; that the most common policy solution is to leverage the state to shelter existing institutions from their mediocrity, whether through corporate subsidies, legacy media handouts, hiking bans, or by growing an inefficient public sector.

Rather than experiencing the inertia and uneven rewards of runaway economic forces, the country’s central challenge with productivity means that conventional centre-right policy fixes—streamlining regulations, fostering competition, eliminating interprovincial trade barriers—continue to find a wide, accessible, and cross-class appeal. That is, even while the Canadian electoral marketplace may have been somewhat reshaped by emergent social divides, most Canadians continue to share the same precise material conditions and interests.

Members of the Iqbal family look on as Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poilievre speaks to the media during an announcement in Brampton, Ont., on Friday, August 29, 2025. Arlyn McAdorey/The Canadian Press.

The future of the Conservative coalition

With the 2025 federal election now five months in the past, the focus of current conservative attention has now turned to the characteristics and consequences of this new coalition: how different is it from its predecessors; how can it best be mobilized; and, in looking forward, whether it can be both maintained and grown through recourse to the same fusionist package. Given the Liberals’ narrow win, the working presumption is that a slight increase in the popular vote share is sufficient for the party to win government.

Among the more popular working interpretations of April 2025 is the idea that it constitutes a total realignment of the Canadian electoral marketplace: that, in parallel with the U.S. and U.K., it marks the point at which the country has now fallen into the distinct camps of the haves and the have-nots. While the centre-right now is now made up of a multi-ethnic and young working class, the centre-left has the Boomers with university degrees and houses.

Aspects of this understanding, being derived from foreign two-party systems, are too exaggerated and simplified. Important qualifications need to be made about the claims of both decisive transformational change and fully consolidated voter blocs. For all the talk of the drift of union voters from the NDP to the Conservatives, for example, there’s minimal evidence that a decisive shift of this kind really took place in 2025. Instead, the party’s working-class support—having gradually come into place over the last two decades—may have already been in place. Likewise, while large shares of new Canadians may have moved rightward, their status as Liberal-to-Conservative voters is not new; they have and continue to be, alongside a large portion of other Canadians, important swing voters with weak party attachments.

Although the realignment thesis may exaggerate the changes, we should not overlook the actual transformations that occurred. For one, the core of the Conservatives’ growth clearly came from, to quote Ben Woodfinden’s analysis, those Canadians for whom “life is much harder than it was a decade prior”; the kind of people—especially young, recently immigrated, or working in trades—who deemed the economic and political status quo to be decidedly against their interests. The transfer of many Boomer homeowners from the Conservatives to the Liberals is, likewise, indicative of the international trend of the move of affluent, educated, and socially progressive voters to the centre-left regardless of age.

However, it seems to me that, rather than amounting to a new or transformed coalition, the support received by the Conservatives in the 2025 election is more accurately seen as a more consolidated, enthusiastic, and mobilized version of the group that has been gravitating towards the Conservatives over the past few decades.

The fact is that the structural transformations that have shaped the contemporary centre-right can be traced back to the early 1990s, if not earlier. This could mean that its relevant political divides—whether that’s between blue collar workers and university graduates, or social traditionalists and liberal progressives—had already been effectively formed by 1997. Indeed, we often forgot about how populist the politics of that decade really were, whether it was the Reform Party, Rush Limbaugh, or the paleocons. We likewise overlook how early the thesis of a working-class realignment was posed.

What’s changed is context and the way these divisions matter and are expressed. That is, things may have grown in coherence and relevance in ways that my analysis was not able to fully capture. It is in the vein, for instance, that Johnathan Hopkin demonstrates that the populism of the 2010s was clearly a response to the 2008 financial crisis; what mattered was not that the event introduced new social divides, but that it delegitimized the globalized liberal economic policy paradigm that had been long-promoted by conservative leaders.

For the Canada of 2025, then, the electoral results reflect how deep-seated the sense of economic unease and national malaise really is. While it may not have introduced novel demographic divides, it has made the existing ones sharper and much more salient. As I argued, though, the only difference here is simply the fact that, due in large part to Canada’s position, liberal economic policy continues to find broad and popular appeal.

Key takeaways

Given this continuity, it’s reasonable to presume that the relationship between economic liberalism and social traditionalism found between 1997 and 2021 also applies to the party now. This is to say that—as indicated by their enthusiasm for the economic agenda maintained by Poilievre—Conservative voters remain unified in their economic preferences and can, consequently, remain generally avoidant of the tensions that have emerged from recent social and cultural divides. Not only do social traditionalists themselves remain averse to state intervention, but the pressing nature of material concerns means that emerging divides or concerns of a more cultural nature—while certainly present in Canada—seemingly remain of secondary concern.

The takeaway here is that the ideal future for the conservatives—for both maintaining a cohesive coalition and winning government—is about more or less replicating the same appeal as 2025: the maintenance of this fusionist economic emphasis.

Indeed, for all the attention the American tariff threat received at the time, the Conservatives consistently performed better on housing and cost-of-living issues. The narrow margin of loss means that, even if the Carney coalition is held, a few percentage points can be simply gained through a more efficient campaign infrastructure.

For now, the most important open question is to what extent Carney’s government can, as promised, alleviate the material and social pressures that have made the Poilievre Conservatives’ appeal so potent. While disappointments will certainly hurt Liberal fortunes, success may be the glue that binds the Carney coalition together, undercutting the Conservatives’ bottom line. Under this scenario, they may indeed need to experiment with cultural issues and new economic ideas.