By 2025, Canada’s federal debt may increase by roughly $716 billion — nearly double our pre-COVID level. And 2020 and 2021 alone account for over $520 billion of that.

With such staggering sums, it’s natural to wonder what this means for the future.

“Workers and families will have to pay the price,” warned NDP leader Jagmeet Singh.

The budget “provides no real fiscal anchor,” observed Conservative opposition leader Erin O’Toole.

Even the government appears concerned. “The government is committed to unwinding COVID-related deficits and reducing the federal debt as a share of the economy over the medium-term,” reads Budget 2021.

But how, you ask?

There are some modest tax changes in the budget, from cigarette tax increases, to vaping products taxes, to taxes on luxury vehicles, boats, and airplanes. But these are modest. The government isn’t lowering spending either. In fact, with significant new commitments in many areas — including $30 billion for child care over the next five years — it is doing the opposite.

Instead, the government is hoping to boost economic growth.

“The best way to pay our debts is to grow our economy,” said Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland.

There’s truth in that, as I’ll illustrate below. But the effect operates very slowly and we will remain exposed to significant fiscal risks. More will need to be done.

Is Our Debt Sustainable?

Let’s get one thing out of the way up front: Canada’s federal debt is sustainable and is not (necessarily) a burden on future generations.

You might prefer more borrowing to fund expanded social programs. Or you might prefer less borrowing. That’s fair enough. But regardless of your personal preferences, our federal government can carry its growing level of debt at relatively low cost into the foreseeable future. After all, what matters more than the dollar value of new debt is how quickly debt is growing relative to our ability to pay. That means looking to the debt/GDP ratio.

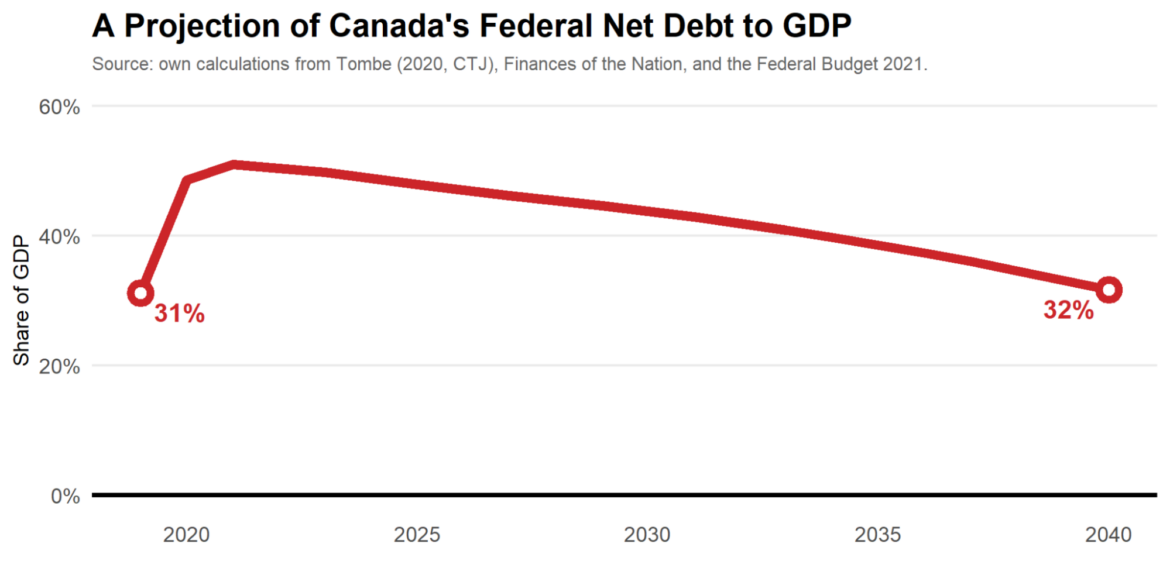

Once we get to 2022 and beyond, when the COVID measures are unwound, Canada’s debt levels grow more slowly than our total incomes. And my own work suggests this may continue. Without going into details, I estimate the government’s debt/GDP returns to its pre-COVID level roughly by 2040 (under current policy, and without a recession in the meantime).

This projection also makes clear why debt is not “shouldered by our children.” There’s no change in current tax or expenditure policies beyond what was announced in Budget 2021, yet debt burdens gradually fall.

This is sustainable. And economic growth is a key factor.

Growing Out of Our Debt?

So let’s return to the minister’s focus on growth.

The government’s primary measure to boost the economy is expanding accessible child care. More accessible child care will increase female labour force participation and employment, thereby increasing overall incomes. There is an important debate over how best to provide effective child care and early learning opportunities. But if it can be achieved, the economic effects are potentially large.

To illustrate, roughly 83 percent of Canadian men outside Quebec between the ages of 20 to 44 were employed in 2019 while only 77 percent of women were. In Quebec, where child care is more accessible, 84 percent of men of that age are employed and 82 percent of women are. If the national gap between male and female employment rates mirrored Quebec’s, overall national employment could increase by nearly 225,000 jobs and the overall economy might grow by roughly 1.2 percent. That may sound modest, but 1.2 percent of Canada’s nearly $2.5 trillion economy is a rather large number — roughly $30 billion per year.

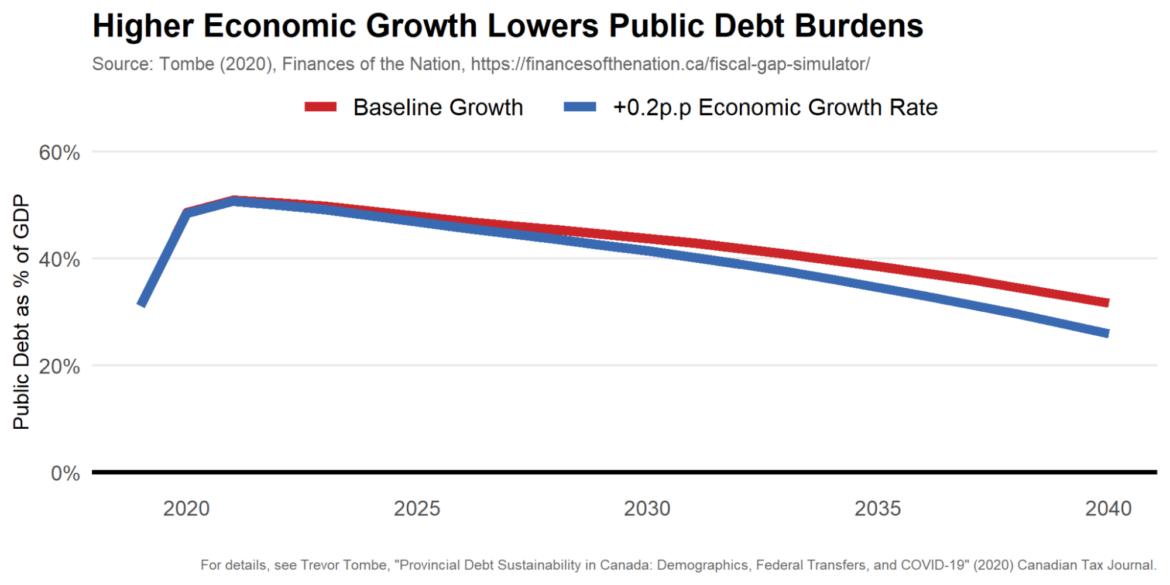

This is a crude back-of-the-envelope illustration, to be sure, but the 1.2 percent gain is identical to what the government estimates in its own budget. So let’s run with it. If it takes 20 years to achieve this boost (again, the government’s estimate) then growth might increase by 0.05 percentage points per year. This increased growth translates into higher government revenues and falling debt burdens.

Just for argument’s sake, let’s suppose the government can quadruple this effect through other programs (infrastructure, education and training, improving regulatory efficiency, trade liberalization, and so on). If growth rates increase by 0.2 percentage points per year, then we return to pre-COVID levels of debt three years earlier by 2037 instead of 2040.

So while boosting growth can help, it’s hard to move the needle quickly so it shouldn’t be the only tool we use.

Fiscal Risks

Bringing debt levels back down matters because we face real fiscal risks if we don’t.

If another recession or two hits, debt will rise. If an expansion continues unabated, debt will fall. We just don’t know which of the two will happen. It may be prudent to prepare for the worst.

Returning to pre-COVID debt levels over the span of, say, 10 years instead of 20 wouldn’t be easy. Increasing the GST by two to three percentage points would be required. Restraining federal spending growth could also help. Increasing the eligibility age for benefits like Old Age Security from 65 to 67, for example, has the equivalent effect on the budget by 2030 of roughly one point on the GST.

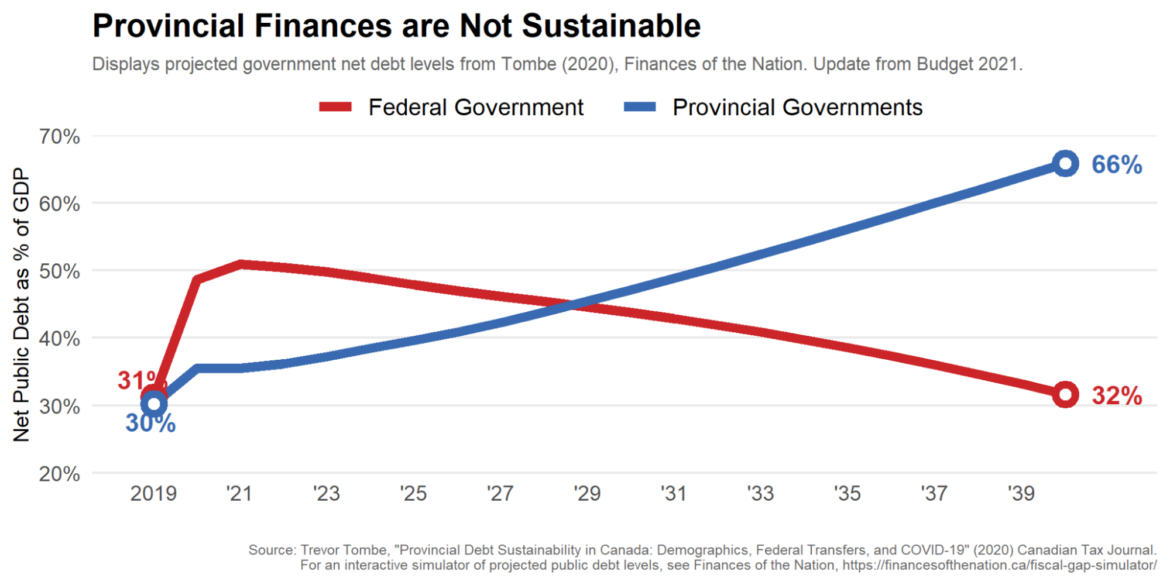

But perhaps more important than federal fiscal risks are the long-run risks facing our provinces. Those governments, after all, bear the full burden of rising health costs from an aging population. And most aren’t well prepared. I plot my projection for provincial debt/GDP levels below. The contrast with the federal government couldn’t be sharper.

How Canada moves forward to address long-term challenges remains an unanswered question. Budget 2021 did little. The government is right to highlight the benefit of boosting economic growth. And reasonable people can discuss the merits of specific programs announced in the budget. But we must not neglect our long-run fiscal challenges, which will only grow larger in time.

Recommended for You

Carney defines his doctrine

Trump’s tariffs, tax shocks, and long-standing stagnation—how Canada can counter emerging economic threats: DeepDive

‘A festival of hot air’: Why it’s time to be done with the tone-deaf Davos elites

Pierre Poilievre needs a foreign policy plan

Comments (0)