The current obsession with the growth of China’s economic and military power is reminiscent of the days of Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Despite the phenomenal economic growth of the Chinese economy over the last thirty years and the flexing of its power via both military prowess and the global Belt and Road Initiative, concerns that China and its economic model are going to bury the West are premature to say the least.

China’s economic performance is not as robust as many would like to think and its bravado on the international stage with its Wolf Warrior Diplomacy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to backfire. Despite the seeming strength of China’s economic rise, its economic mass, and its successful approach to trade and development, its position remains fragile.

China’s exuberant diplomacy is fueled by a sense of insecurity which in and of itself is a concern for global stability in the 2020s.

China’s economic growth was driven by a highly focused development program that made effective use of the global liberal economic order constructed by the United States in the period after the Second World War.

China’s rise was facilitated by a global community that believed that with growing incomes and development, China would become a full partner in the democratic liberal economic order. However, in the end, China has pursued a mercantilist trade policy that grows its exports while limiting competition from imports.

While China has private companies, its state-owned companies are the more prominent international investors in building an integrated supply and production chain. As for democracy, free speech and human rights, the record there is quite plain for all to see.

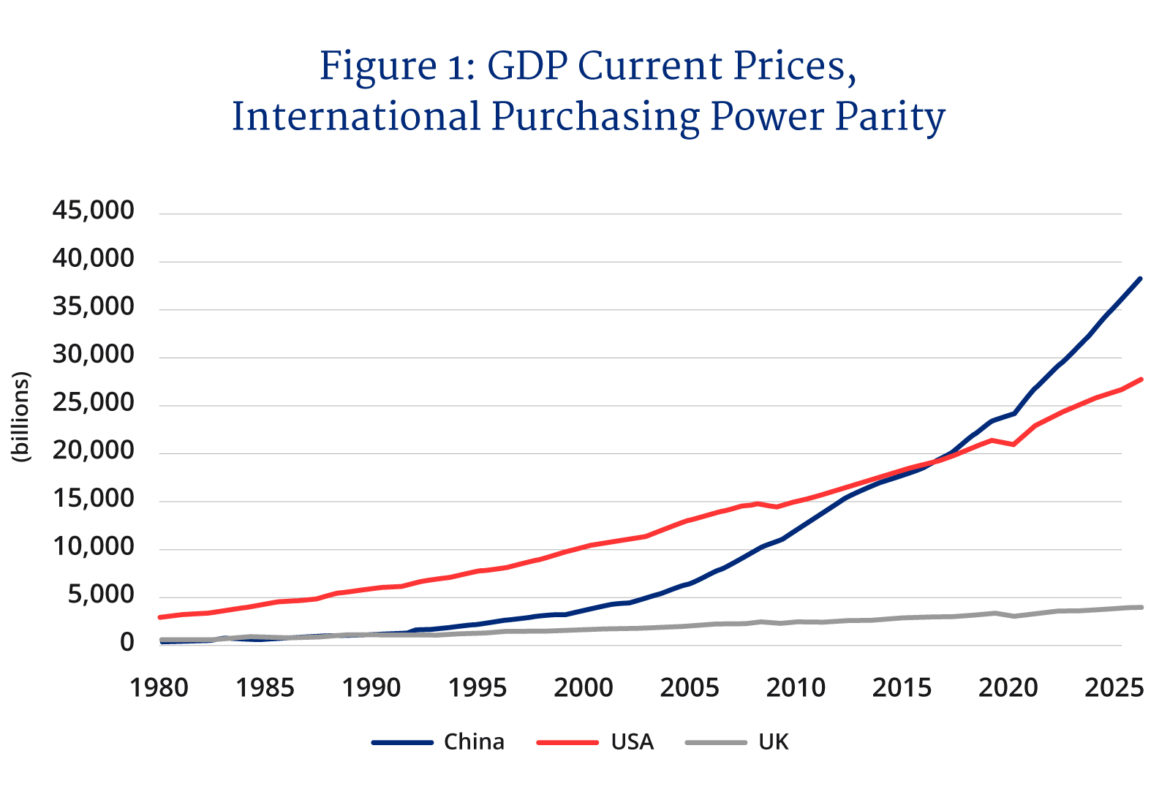

On the surface, the Chinese economy is a behemoth that has already surpassed the United States in terms of its sheer size. When one looks at total GDP in billions of international purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars — a metric used to compare economic productivity and standards of living between countries — China passed the United States in 2017.

China may be about to run out of steam given that its large population slows its per capita output growth.

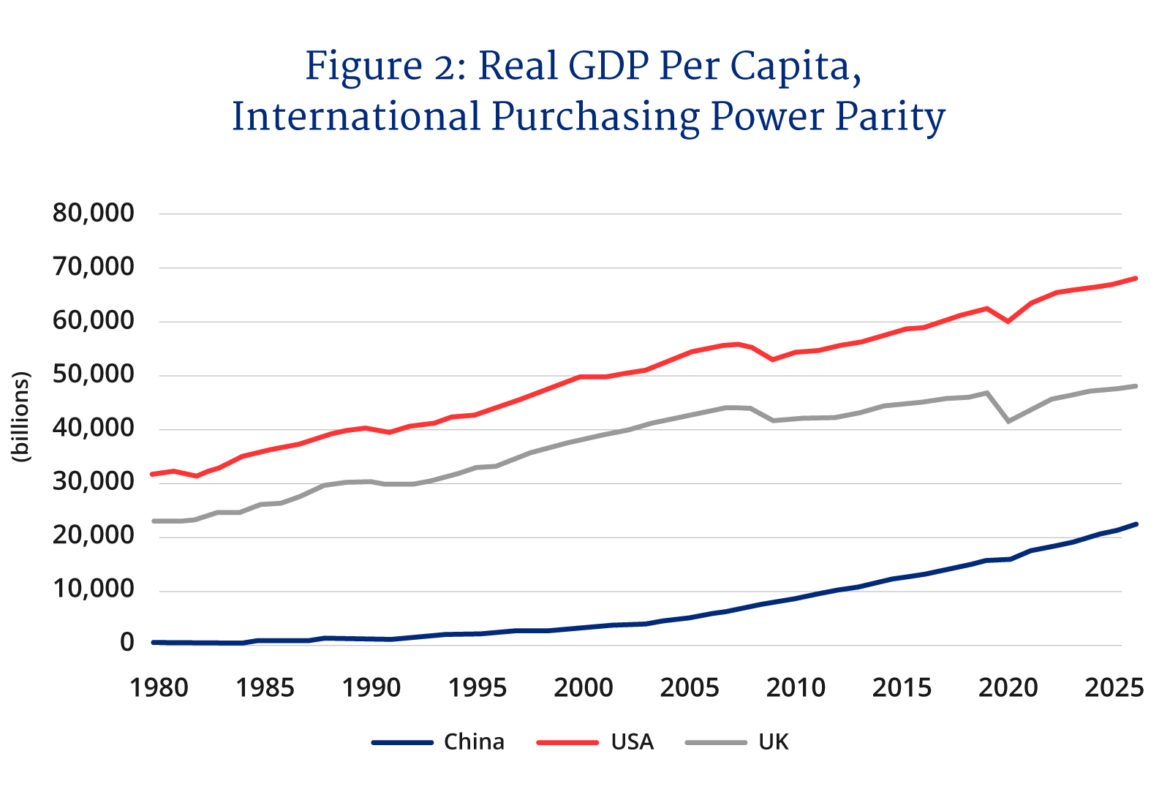

However, there is a difference between extensive and intensive economic performance — that is the total size of the economy versus its size per person. It is not that market size and total output does not matter but it is output per person and its growth that matters more as an indicator of welfare and development over the long run.

Since the start of modernization in the 1970s, China has seen both its total and per capita GDP grow.

Using the International Monetary Fund-World Economic Outlook database numbers, since 1980 China has seen its GDP in international purchasing power parity dollars grow from $303 billion to $24.1 trillion in 2020 compared to the United States which grew from $2.8 trillion to $20.9 trillion.

This phenomenal growth was a nearly 80-fold economic expansion by China against a U.S. economy that only expanded by about seven times. China has become the 21st century manufacturing workshop of the world and also a major international market particularly for resource products.

But China’s population is much larger and has also been growing. While the total size of the Chinese economy is now bigger than America’s, its output per person still has far to go.

In 1980, per capita Chinese GDP (in PPP dollars) was $674 compared to $31,894 for the United States. In 2020, it had grown to $16,297 compared to $60,114 for the United States.

Per capita incomes in China on average are still only just above one-quarter those of the United States.

While China has several hundred million people with middle class incomes comparable to the developed world, a far larger proportion of its 1.4 billion people still faces much poverty. And, even for its middle-class winners, the pace of work is grueling in terms of the long hours required, with younger generations now wanting more balance and a retreat from the traditional work culture.

By way of another comparison, on its path to becoming a global economic powerhouse, the United States surpassed Britain’s total GDP in the late 1870s and its per capita GDP on the eve of the First World War.

Yet, in 1870, the total size of China’s economy was actually larger than that of either the U.S. or the U.K., but its per capita GDP was 17 percent that of the U.K. and 20 percent that of the U.S.

China now again has a bigger GDP than the United States, but it has been there before. However, when it comes to per capita GDP, not that much has changed and there is a long way to go.

China also may be about to run out of steam given that its large population slows its per capita output growth. It also has a rapidly aging population that potentially limits its future output growth though this is also a problem affecting much of the developed world. And like the developed world, China has also run up a rather large stockpile of debt.

While China has developed greater capacity for research and innovation, it is telling that even during the pandemic, ultimately the most successful vaccines were all developed in IMF advanced economies.

Moreover, China now faces pushback from other countries with respect to trade and investment given that it is being viewed as a non-reciprocal player when it comes to international trade. As well, its reticent behaviour early on in the COVID-19 pandemic in allowing the virus to spread around the world because of a reluctance to fully acknowledge the problem has not helped matters.

Given the economic extremes generated by China’s rapid economic growth, navigating its domestic political and social tensions makes foreign adventurism and bravado an attractive option for an authoritarian leadership seeking to divert the masses.

It also is being driven by sense of urgency given that in seeking to reassert its dominance and cement itself a new place in the world economic order, China is running out of time. Burying the West is going to be the least of its challenges.

Recommended for You

‘It looked a lot like an elite moral panic’: The Full Press on the journalist brawl at the English leaders’ debate

‘Crooks, crackpots, cowards’: David Frum on the Trump administration chaos consuming American foreign and economic policy

‘It will make for an exciting election day’: Ginny Roth on the Conservative campaign strategy heading into the final days of the election

Brad Tennant: The poutine-petrol alliance—why Alberta and Quebec should team up in their fight against federal overreach