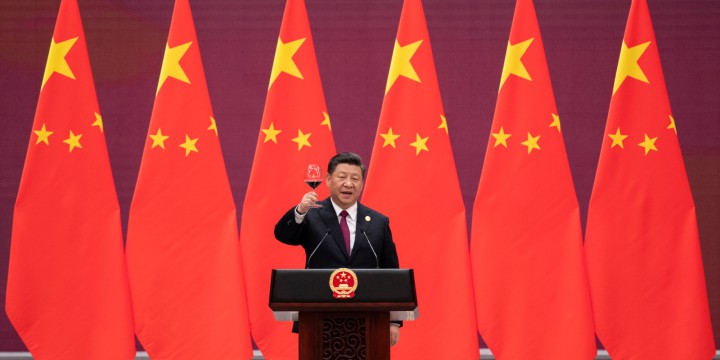

‘An increasingly intense rivalry’: Foreign policy expert Aaron Friedberg on why decoupling from China is a costly but necessary decision

This episode of Hub Dialogues features host Sean Speer in conversation with Aaron Friedberg, a professor of political science at Princeton University and one of America’s leading foreign and security policy thinkers, about his fascinating new book, Getting China Wrong.

They discuss why integration with China did not lead to its liberalization, the rising importance of economic blocs in geopolitics, and why arrogance may be China’s fatal flaw.

You can listen to this episode of Hub Dialogues on Acast, Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, or YouTube. A transcript of the episode is available below.

Transcripts of our podcast episodes are not fully edited for grammar or spelling.

SEAN SPEER: Welcome to Hub Dialogues. I’m your host, Sean Speer, editor-at-large at The Hub. I’m honoured to be joined today by Aaron Friedberg, a professor of political science at Princeton University and one of America’s leading foreign and security policy thinkers. He’s also author of the fascinating new book, Getting China Wrong, about the failure of Western policy vis-à-vis China over the past 30 years.

I should say that Professor Friedberg’s scholarship and commentary have significantly influenced my own thinking and writing on the subject, and so it’s a great pleasure to speak to him about his much-anticipated book. Aaron, thank you for joining us on Hub Dialogues, and congratulations on the book.

AARON FRIEDBERG: Thank you very much for having me.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s start with a scene-setting question. What was the West’s strategy of engagement with China, when did it start, and what were its stated or anticipated goals?

AARON FRIEDBERG: There really were two variants of the overall strategy of engagement. The first one begins in the early 1970s with the tentative reestablishment of relations between the United States and China during the Nixon administration. During that period, the goal of American policy, pretty much openly stated, was to build up China as a counterweight to what was perceived to be the growing power of the Soviet Union. That was really the objective. There was no concern expressed about the nature of China’s political system. There may have been some hopes that it was reforming economically, but the goal was strategic.

In the book, I describe what came next as Engagement 2.0, and it’s a variation on what came before. It’s much broader, so it’s a broad economic engagement, as well as political, diplomatic, educational, scientific cooperation—across-the-board engagement. The rationales were different. There were really three. One was to try to draw China into the existing international system, the so-called liberal international order, at the end of the Cold War, and the thought was that by welcoming China into existing institutions and making it a full member in that system, China’s leaders would come to see their interests as lying in upholding the system and not trying to really change it or overthrow it.

The second objective, and again, this all really begins at the end of the Cold War, so the early 1990s, was through economic engagement, through trade and investment, to set in motion forces that it was believed would lead progressively to the economic liberalization of China. China would move over time towards a more market-based economic system that would come eventually to resemble ours, basically, or those of other advanced, Western countries. Last, but not least, was the belief and the expectation and the hope that through engagement—especially through economic engagement which would promote trade, which would promote growth, which would lead to the growth of the middle class in China—we would set in motion forces that would lead, ultimately, to the political liberalization of China, to its democratization. That was a long-term goal, but I think it was an important part of the rationale for the strategy of Engagement 2.0.

SEAN SPEER: You make the case in the book that on balance the results of this strategy have been injurious to the interests of the United States and the West more broadly. If you were scoring this strategy, what were its key outcomes, good and bad?

AARON FRIEDBERG: If I was grading it, I guess by those standards, by those expectations that I just set out— a responsible stakeholder in the existing international order? Looks like a failure. Economic liberalization? In fact to the contrary, China has been moving towards increased statist, mercantilist economic policies. Politically, of course, it’s become even more repressive than it was before. Arguably China is more repressive today than at any time since the Cultural Revolution. I think by all of those standards, engagement was a failure.

People who argue otherwise would say, “Well, there were economic benefits from engagement. Americans got lower-cost goods, and that to some degree on some issues, that sometimes China was cooperative with the United States in pursuing common goals. I think both of those are true to a degree, but not nearly to the extent that the advocates of engagement claim.

SEAN SPEER: A major reason for the strategy’s failure is that, as you outline in the book, China anticipated our goals of engagement and developed a counter-strategy to leverage the economic, technological, and even strategic upside without conceding political change or risks to the Communist regime. Peter Thiel has described this as a strategy to have Perestroika without Glasnost. How was the Chinese regime able to strike such an extraordinary balance that the Soviet Union ultimately couldn’t?

AARON FRIEDBERG: One reason, and I think it’s an important one, was that the Chinese leadership had the Soviet example to learn from, and they watched what happened in the Soviet Union under Gorbachev as the system unraveled and the country fell apart and the Communist party lost power. They were determined never to allow that to happen to them. One of the points that I make in the book is that the most important feature of the Chinese political system is that it’s organized along Leninist lines. It’s a system where the party is determined to maintain its exclusive grip on political power and to exert control over everything that goes on in society, in the economy, and so on.

The Chinese leaders learned from the Soviets. Xi Jinping is arguably obsessed with Gorbachev and with the collapse of the Soviet Union. He gives speeches where he talks about. They’re haunted by that. Then from observing what had happened there, the CCP developed what I would describe as an evolving strategy for maintaining control. I think it had three elements, and at various times different elements were emphasized and others de-emphasized.

First, co-optation, so initially trying to encourage people to continue to support the regime with the promise of economic gain, and the fact that people were improving their lives and had reason to think that they would be able to continue to do that.

Second, repression. The regime never gave up on repression. After Tiananmen, it arguably became more surgical and preemptive in identifying dissidents and making sure nothing like Tiananmen ever happened again.

The third element is what I would call indoctrination, especially after Tiananmen the leadership, starting with Deng Xiaoping, who really said this very explicitly in conversation with PLA generals a few days after Tiananmen, he emphasized, or expressed the concern that the CCP was losing the support of the Chinese people and that it had not done enough to refresh and strengthen its legitimacy.

From that point onwards the CCP began what came to be referred to as a campaign or a system of patriotic education, which emphasized essentially nationalism, and initially a kind of backward-looking nationalism that emphasized the so-called Century of Humiliation, all the bad things that had been done to China by foreign powers, and emphasized also the Communist Party’s central role in freeing China from that oppression. I think what’s happened in the last few years, and this really started under Hu Jintao it didn’t begin with Xi Jinping, but what’s happened, I think, is there’s been an increase in repression—that’s inarguable.

There’s also been an increasing emphasis on indoctrination and on ideology. Now a more positive form, as well as the negative, talking about the China Dream, the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, and although co-optation hasn’t faded away entirely, especially with the slowdown in economic growth, I think the leadership realizes they can no longer count on being able to promise more economic benefits year after year. That’s one of the reasons, it’s an important reason, why it’s increased repression and increased indoctrination. They’ve been very flexible and they’ve adjusted.

SEAN SPEER: Professor Friedberg, we’ll come back to some of those points, particularly the current state of China’s economy and its political system, but before we get there, I just have to ask the obvious question, which is why did it take us so long to realize that our strategy was a failure? Was it an ideological failure, did it reflect the overwhelming influence of commercial interests, or are there some other factors to explain why it took us so long?

AARON FRIEDBERG: That’s a very good question. I think it’s easier to understand why we started with engagement than why we stuck with it as long as we did. In fact, I would say the policy at the outset was not a blunder, but it was a gamble that didn’t pay off and the question is, why did we keep doubling down on this bet even as the evidence of it not paying off accumulated. There are a whole lot of reasons. You mentioned a couple of them, there’s wishful thinking, theoretical thinking, believing that because economic growth has led to political liberalization in other parts of the world at other times in history it must happen in China as well.

There’s real arrogance. The idea that history has ended and we won the Cold War. Our system is triumphant. We have all the answers and everybody is just going to want to follow our model and you can’t underestimate the impact of that. Commercial interests, definitely. And especially as time went on and more and more individuals and companies and economic sectors began to make money, although they also had problems and those problems grew, they had a strong interest in keeping the relationship on an even keel and pressing the U.S. government, but also other Western governments to try to keep relations smooth so that trade and investment could continue.

In the case of the United States there’s also distraction. I think U.S. policy towards China would have turned I think in the direction that it has turned more recently sooner if not for 9/11, if not for the focus on terrorism and on the Middle East, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

And last a factor that can’t be ruled out but is very hard to evaluate: That is Chinese Communist Party, political warfare or influence operations which they’ve waged on a vast scale, I think arguably quite successfully in a whole array of Western countries, to try to win over elites and shape perceptions and encourage people in our system and in other democratic systems to stick with the policies that they were pursuing. To persuade them that they were working, to persuade them that there was no alternative. It’s all of those things together that I think kept us locked on this course,

SEAN SPEER: As you mentioned it’s fair to say that several factors, including, but not limited to, the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to a growing recognition of the need for a new strategy vis-à-vis China. But this is hardly a universal view. You called the strategy of Engagement 2.0 a bet. There are those who continue to argue that we ought to double down on that bet. That is to say that the process of market liberalization and ongoing economic cooperation will ultimately produce political liberalization in China and a reliable global partner. What would you say to these voices? Why are they still getting it wrong?

AARON FRIEDBERG: Well, I think somebody once said the definition of insanity is to keep doing the same thing over and over again even when it doesn’t work—I don’t think people are insane, I just think they’re misguided—but I think some people still underestimate or don’t understand the Chinese Communist Party in part, at this point, it’s because they aren’t paying enough attention to what the CCP leaders are saying. I think if they were, they would have fewer doubts about the need to change direction, and that’s different than it was in the 1990’s and the early 2000’s where the leadership was much lower key and much less confrontational than it has become. So they’re not paying attention.

I think the current thrust of what the CCP is trying to do across a range of domains has to be blocked or stymied or defeated in order for there to be any possibility of China changing direction and I’m concerned that business as usual, or making only minor adjustments in what we’re doing are going to leave us weaker and give China or China’s leaders the opportunity to further build up their strength, which is going to increase the danger of miscalculation on their part and confrontation and conflict down the road. So yes, I realize that some people don’t accept this, but I think it’s harder and harder to justify anything that resembles the policies we’ve been pursuing for the last 30 years.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s talk a bit about what a course correction would look like. You’ve previously said, “We’re now running behind it [that is the U.S.-China relationship] trying to figure out exactly what we want it to look like.” The book identifies some key components of a new strategy, including a degree of industrial reshoring, more stringent foreign investment restrictions in strategic areas and something of a military buildup. Do you mind elaborating on these issues and areas that you think policy makers ought to be focused on?

AARON FRIEDBERG: There really are four, and I talk about them in the book, four lines of effort. The first has to do with education and mobilizing support in democratic societies and I think that’s going to require our leaders to speak more candidly and more bluntly about the challenge that we face. There’s still a tendency to try to soft pedal things, maybe in the belief that we’re somehow going to avoid antagonizing the CCP by not speaking more bluntly to our own people.

If we can’t persuade our people that things are necessary, including things that are going to be costly, we’re not going to be able to respond effectively. So that’s number one. Number two, we have to do things and I think we are starting to do things to counterbalance the growth of China’s power, in particular it’s military power. This is going to require a mix of military and diplomatic efforts to try to maintain a balance of power, particularly in the so-called Indo-Pacific region that will continue to deter China’s leaders from ever using their growing strengths to try to forcefully accomplish their objectives.

That is a real contest and it’s getting more difficult because China has undertaken one of the biggest and most broad-based military buildups in history over the last 30 years and we have to do more to balance that. I think we also need to restructure our economic relationship with China to a considerable degree, and perhaps we can talk about that at greater length because it’s important but also difficult.

The current economic relationship is unfavourable to us in a variety of ways. It damages our ability to maintain our technological advantages and in various ways it gives China leverage over democratic societies through the threat of cutting off access to their market. We’ve seen in the case of Russia doing similar things, just how dangerous that can be.

The last piece barring a phrase that CCP theorists use is waging discursive struggle, which really means ideological struggle. By that I mean we have to, in the democratic world, we have to emphasize our values and the commonalities among us, and also the differences between our system and the CCP system and we need to speak more bluntly about the failings of their system.

Now, this is not just a matter of talk. We also have to actually prove that our system works and works better, and that’s directed in part at China and the Chinese people, but it’s also directed at a broad swath of the world, particularly the developing world where China is trying very hard to convince people that they have the superior model.

It’s really those four things and of course they involve a great deal and they’re going to take time and cost money, but those are the main lines of effort.

SEAN SPEER: It’s such a rich answer Professor Friedberg. If I can just pick up your first and second point, that is education domestically and globally, and then preserving a balance of power globally and in the Indo-Pacific region, may I ask your thoughts about the policy of strategic ambiguity with respect to Taiwan?

In recent months President Biden has signaled a preparedness to defend Taiwan in the event of Chinese aggression. Do you think he’s right to move beyond strategic ambiguity in light of the context that we’ve been describing today?

AARON FRIEDBERG: He hasn’t fully abandoned strategic ambiguity. I guess he’s moved a half step away from the policy of the last 40 years which has left open the question of the conditions under which the United States might become involved militarily in a conflict between Taiwan and the mainland. Honestly, I don’t see a great deal of advantage for us in abandoning that policy. For one thing, I think the CCP leadership is convinced already that whatever we say, we’re going to become involved in a conflict and come to the aid of Taiwan. I don’t think we’re going to deter them more by saying that we would do that.

There’s also some risk of spinning them up even more than they currently are and there’s some risk also of what the economists call moral hazard. If you tell people you’re going to protect them no matter what they do, sometimes they’re going to do things that are reckless and dangerous. I don’t think we need to be doing that.

The thing that we need to do, or the things that we need to do, are help Taiwan to strengthen its capabilities, to enable it to better defend itself, at least for a period of time against the Chinese attack. We and our allies also have to strengthen our capabilities to project power into the region if we choose to become involved, to be able to do that and succeed. China’s been working very hard, not only to build up an overwhelming capability that’s targeted on Taiwan, but also to develop capabilities that are meant specifically to deter us from getting involved in a conflict or they hope to defeat us if we were to do that. That’s part of the counterbalancing that I mentioned earlier.

SEAN SPEER: Let me take up the issue that you raise about the economic relationship between the U.S. and China in particular, and more generally the system of globalization in which we’ve lived under really since the end of the Cold War.

In a new essay for the Texas National Security Review, you anticipate an end to globalization and speculate on five post-globalization scenarios, including a partial liberal trading system that involves the United States and its key allies. Do you anticipate a process of so-called “decoupling”? If so, what will be its costs and consequences?

AARON FRIEDBERG: Well, I should start by saying that the system that we helped to create and maintain after the end of the Cold War, the economic system was not a fully global system. It was a partial system that came to include most of the other democracies in the Western hemisphere, Northeast Asia, and also in Western Europe, because the Soviet Union had its own bloc and China for a long time stayed out of the global economy as well. We had a partial liberal system, partial open economic system, historically open or more or less open global economic regimes have existed under one of two conditions. Either when there is a so-called, hegemon: a really powerful disproportionately strong and wealthy state that’s willing and able to pay the price that’s necessary to keep that system open.

Or when you have a high degree of cooperation among like-minded states that are playing by the same rules. I think increasingly it’s become clear that we don’t have either. The United States is not as dominant as it once was, and China is growing. We certainly don’t have agreement between the United States and the other democracies and China about the way in which the economic system is operating—that’s one of the main sources of friction and tension between us now. When you don’t have those conditions, what tends to happen is that a global economy will collapse and fragment.

I should say that what we did after the end of the Cold War was try to build a truly global system. We had this partial system when the Cold War ends, the Berlin wall comes down, Soviet Union fragments. We’d already started engaging economically with China. Now we’re going to bring Russia and the former Soviet Empire into it. This was going to be the second great age of globalization, the first one being before the first World War. That’s what’s coming to an end. The question is, what is going to come next? In the article as you mentioned, I talk about a number of different possible models. I don’t think it’s going to fall apart entirely where everybody’s going to go to autarky and try to simply rely on themselves for everything they need. China is not wealthy and strong enough itself to become the hegemon to build a new Sino-centric economic system.

I don’t think we’re going back, we’re not going to fix things and go back in the direction that we thought we were moving. Then I think the two possibilities are economic blocs, and one possibility is that those might be organized regionally. You might have an Asian bloc that would be largely centered on China, maybe a Western hemisphere bloc that was largely centered on the United States, perhaps a European bloc. The other possibility is that those blocs would be organized essentially ideologically. In the article I talk about them as value-based blocs. In my view, that would really mean going back to the partial liberal system that we created during the Cold War.

It’s not unthinkable, it’s something that we had before and it worked quite well. If you look at the countries that would be in that system, if you were able to create it, they collectively control more than 50 percent of global GDP and China at this point is only 17 percent. That would be a substantial concentration of economic power. I don’t think economic relations between, if we had such a system and China and whatever countries were in its bloc, would collapse. I think there would be trade and exchange, but there would be a significant degree of restructuring or decoupling or what I’ve called partial disengagement.

In fact, that’s already underway. It’s really, in my view, it’s a question of how fast and how far it goes. We, and now others, especially in Europe, but also in Asia are imposing tighter restrictions and screening of Chinese foreign direct investment because people have realized that Chinese have been coming in and buying up technology and taking it back and, as they say, indigenizing it and building up their own industries and competing and driving our companies out of business. There are more export controls on the export of certain high technology items. I think those are going to expand because we see that China will use those, again, to try to gain advantage, both commercial advantage and military advantage. Increasingly there’s talk about outbound investment restrictions.

At the moment, there are hundreds of billions of American dollars that flow into Chinese companies, including companies that work directly for the People’s Liberation Army, as well as companies that are involved in developing surveillance technology of the sort that’s used to maintain control of China’s ethnic minority Uighur population in western China. That just doesn’t make any sense. We’ve realized we’ve learned as a result of the pandemic that in fact, we’re very dependent on China as the sole producer or the primary producer of a number of things that are greatly needed in a medical emergency, including masks and a lot of pharmaceutical products.

I think people realize that that’s a dangerous situation to be in because it gives a potential opponent leverage over you that it might choose to use for its own reasons. I mentioned before the Ukraine crisis and the experience the Europeans have had with Russia. I think that’s a warning that we should heed. The Europeans were, especially the Germans but others too, dependent on Russia, primarily for energy. That was the one big thing that Russia had going for it, also some minerals. Right now, the democratic countries because of the evolution of these supply chains have become highly dependent on China for a whole variety of manufactured goods and materials, which if they were cut off would cause parts of our economy to grind to a halt.

We don’t want to be in that situation. We’re going to have to make changes. These are going to be costly. There will be costs of transition. I don’t know anybody who does know how exactly to calculate those costs, but it seems to me it’s better to pay those costs now and make these changes rather than run the risks of being vulnerable and being exposed to leverage or disruption imposed by China in the event that we do get into some confrontation with them. This is going to be a slow process. There’ll be a lot of resistance to these changes because there are still companies and sectors of our economies that benefit from the status quo even if the status quo now doesn’t serve the best interests of our countries as a whole.

SEAN SPEER: Those are just tremendous insights Professor Friedberg and it seems to me it’s incumbent on policymakers to talk about those trade-offs now so as to build the political support for them.

You talked about the growing geopolitical and technological rivalry. Let me ask about that. How would you assess China’s strengths and weaknesses? What might its combination of slowing economic growth, which you mentioned earlier, its increasing domestic political crackdowns, and aging population mean for the country’s internal dynamics and its leadership’s strategic thinking?

AARON FRIEDBERG: Well, this is a very good and very difficult question and things are greatly in flux. One thing, just an observation and historical observation, and I’m not saying that there’s a perfect parallel here, but in the latter stages of the Cold War, you had many people who emphasized the Soviet Union’s strengths, particularly its military strength and others who talked about it societal and economic weakness. The two groups tended to argue with one another. In fact, what we see in retrospect was that both were right. They were just looking at different parts of the elephant. I think China too clearly has a mix of strengths and vulnerabilities. I guess I would say under the plus side for China the first is clearly it’s now its economic mass, the result of this rapid growth, its generated tremendous resources which have allowed China to engage in this military buildup without increasing the burden of that buildup on their economy.

Their economy is growing so fast that they could grow their defence budget almost as fast without increasing the percentage of GDP that went to defense—that may no longer be possible, but they have a lot of economic resources and that’s critically important. Whatever their problems are, those resources are not just going to evaporate. Their system of government has many, many disadvantages, but there is a unity of effort that’s possible in a system that’s not democratic and has this pyramid structure with the party controlling and monitoring everything that goes on.

We talk about whole of society and whole of government. When you have these conversations with people in Washington, people say it, and then the rest of the room, everybody rolls their eyes because they know how difficult it is to get any kind of unity of effort even within government, let alone society as a whole, in the absence of something like a world war that really mobilizes people. China has this unity of effort. I think they also have pretty clear objectives. There are advantages to being a follower rather than being a leader. You know which direction you’re going, you’re focused on that and you’re working towards those goals.

We’ve been at a loss, I think to define what our objectives are. At the end of the Cold War, again, we thought, well, we’re going to create the perpetual peace and an integrated global economy and democracy will spread. That hasn’t worked. We’re not exactly clear what it is we’re trying to do right now. I think China’s leaders for better or worse are.

Those are pluses, but they’ve got a lot of minuses. You mentioned the slowdown of economic growth, which is now very evident and it has some probably transient causes. COVID lockdowns are obviously contributing to that, but it has deeper roots as well.

Broadly speaking, I think the essence of the problem is that China’s leaders have failed to devise a new model for generating economic growth. For a long time, they relied on massive investment, state-driven investment in infrastructure and residential construction and so on, and also exports. That model has lost its potential to sustain growth. The leadership has not come up with an alternative. Western economists thought that once that model exhausted itself, China would have no choice but to move in the direction that we wanted them to move, to increase the role of the market, to pull the state further out of the economy, and so on.

That was what was expected, particularly when China was brought into the World Trade Organization at the turn of the century. But they haven’t done that. As I argue in the book, it’s because they see that as potentially weakening the party’s grip on power. What they’re trying to do instead is to generate growth through massive investment in technological advances, which they hope will increase productivity, which will enable them to continue to grow even as their working-age population shrinks.

Just to mention quickly three other liabilities, the CCP regime has to expend enormous resources on monitoring and repressing its own people. I don’t know what percentage of GDP it is, but it’s not trivial. By their own account, a few years ago, their spending on domestic security exceeded their spending on their military budget. That’s not very efficient and the costs of repression are probably going up. Their system because of its centralization is also prone to rigidity. The fact that so much power is now concentrated in the hands really of one man, I think further enhances the danger that the system will not be able to adjust and will stay locked onto policies which might prove to be disastrous.

The last thing I’d mention—I mentioned our arrogance, going back to the end of the Cold War. There’s a good deal of arrogance. There’s always a lot of arrogance to go around and there’s a good deal of it on the Chinese side right now. They really do believe that, as they say, the West is declining, the East, by which they mean China, is rising. They really do believe that their system is going to prove to be superior to ours. I think they’re getting out ahead of themselves. That’s part of the reason that they’re encountering difficulty now is they’re pushing too far too fast and generating a backlash. That may be in the end, the fatal flaw in what they’re trying to do.

SEAN SPEER: You’ve been so generous with your time. Let me just ask a penultimate question before ending with one about Canada, if that’s okay. Are you surprised that there have been few mainstream calls for China to pay reparations to the U.S. and others for the Chinese government’s failure to inform the world of the coronavirus? If so, why do you think the idea hasn’t gotten much traction?

AARON FRIEDBERG: Well, I think such demands would be understandable given the enormous human and financial costs the pandemic, the end of which we have not seen. In my view, they probably also would be justified because there certainly seems to be evidence that the CCP regime badly mishandled the early stages of the pandemic. It’s not clear that they could have prevented it entirely, but they certainly made it worse by the way they dealt with it initially.

Yet doing anything like this would just be impractical. I mean, for one thing, you can’t prove it. How do you prove liability? It’s just impossible. They’re not going to go along with objective investigations. Moreover, even if some international body did come to the conclusion that they were responsible and liable in some way, there’s no way of compelling them to pay those costs.

However, that said, I do think it’s important to continue to press on this question of how exactly this happened. That’s partly because we need to learn so that we can do better if and when this thing happens again, but also there is a diplomatic and strategic element to this.

This is a little bit Machiavellian, but I think what we’ve seen is the CCP regime is behaving, and has since 2020, behaved in ways that suggest that they have a guilty conscience. I think they know that they were responsible in part and they’ve anticipated pressure. They’ve responded in a furious way. This is why they’re imposing strict economic sanctions in Australia because Australians had the temerity to call for an objective investigation. They’re trying to squelch any movement in that direction. But that behaviour, not only against Australia but also in Europe and other parts of the world, has contributed to a real backlash against China.

If you look at public opinion polls in the last year or so, across the democratic world, there’s a dramatic change in attitudes towards China and more people express negative views and express concerns about China many more than did previously. It’s clear exactly when that happened. It’s right at the time of the outbreak of the COVID pandemic. I think given my view of where we’re going and where we need to go, that shift in attitudes is a good thing because it should enable democratic governments to do some of the things that I’ve described, that we really need to do. In this way, as in some others, the CCP at times is its own worst enemy

SEAN SPEER: In light of where you think we’re going, what’s your advice for Canadian policymakers? How should Canada, the quintessential middle power, navigate this new world?

AARON FRIEDBERG: Well, I think if you look back over the last two years, Canada has really shown in my view, admirable determination, but also restraint in standing up to what was really extraordinary Chinese pressure. Nothing like this against an advanced industrial country like Canada, kidnapping of Canadian citizens essentially, blackmailing Canada’s government to try to get it to change its policy.

Although I’m not an expert on Canadian politics, I have Canadian friends who describe what appears to be a process of moving towards a more realistic policy towards China, similar to the process that’s been unfolding in the United States, maybe we’ve got a little bit of a head start, but also in Europe and in other parts of the world. I think it’s important to continue down that path and not to have the illusion that somehow now that this immediate crisis has passed, you can go back to business as usual.

Last but not least, it’s important for Canada and for the United States and for the other democracies to work closely together, whatever our differences, whatever our aggravations with one another may be, we have a lot more in common than divides us. I think we’re on one side of an increasingly intense rivalry with authoritarian powers like Russia, but also even more importantly, China. Benjamin Franklin is supposed to have said “we must all hang together or we will hang separately.” I think that applies to the democracies.

SEAN SPEER: Well for Canadian policymakers and Canadians in general who want to understand how Canada ought to navigate this new world, I strongly recommend they read Professor Aaron Friedberg’s new book, Getting China Wrong. Professor Friedberg, thank you so much for joining us today at Hub Dialogues. It’s been an honour.

AARON FRIEDBERG: Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity.