I have long been fascinated with ideas about self-improvement and peak performance. Truth is, that fascination probably has to do with my own failure to realize my full potential. But curiosity around what makes people perform better and reach better versions of themselves is a line of inquiry that I have been drawn to for many years.

To satisfy this curiosity, I spend a lot of time reading books, listening to podcasts, and watching expert videos. I’m the first to admit that learning about the psychology of self-improvement is a lot easier than putting the various techniques into practice. While I’m imperfect, the pursuit, I think, is still a worthwhile one. Having the self-awareness to realize one’s shortfalls and recognize areas of improvement is at least half the battle.

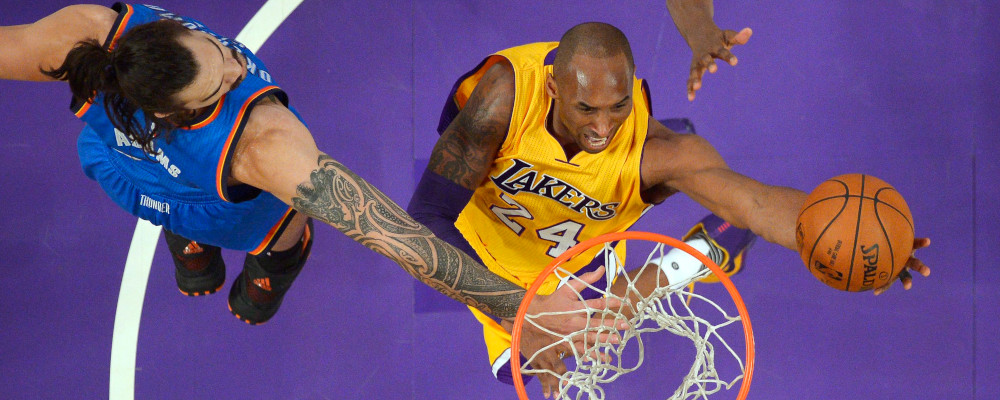

The latest book in my educational journey is Winning: The Unforgiving Race to Greatness by Tim Grover, famed trainer to elite athletes including Michael Jordan (his first ever professional client), Kobe Bryant, and Dwyane Wade among others. It’s a phenomenal read. And highly motivating. At the same time, it will rub some people the wrong way and may even be perceived as harsh, extreme, and unhealthy.

There’s some truth to that. The book isn’t for everyone. It’s a brutally honest perspective about what it takes to be an elite performer—not just in sports but in all facets of life. To be clear: it’s not a book about self-improvement per se. It’s about superstar performance and the obsession required to be the best at what you do. And Grover doesn’t sugarcoat what it takes.

At the outset, he asks readers to think about how they define “winning.” While the uninitiated might use terms like happy, glorious, and other positive descriptors, Grover bluntly describes winning as hard, unpolished, and unforgiving. According to his late client Kobe Bryant, winning is simply: everything.

Grover has done multiple interviews on his book and many articles summarizing the book’s insights are available on the web, so I won’t go into much detail here. The road to greatness, according to Grover, is based on 13 principles that he calls the Winning 13. He ranks all principles as number one because each is equally as important as the others. In other words, winning requires following all principles. And winning can’t be owned; you can only “rent it”—staying on top is a never-ending cycle.

If I try to succinctly summarize Grover’s winning mentality, the word sacrifice immediately comes to mind. There are no shortcuts. Trade-offs abound on the path to winning. You need belief in yourself, discipline, and an unwavering focus on your craft; often that comes at the expense of other life priorities. In Grover’s framework, “winning wants all of you; there’s no balance.”

If it sounds extreme, it’s because it is. Sometimes we romanticize what it takes to achieve superstar status in sports, music, the arts, and business. Grover aims to instill realism by describing his observations, from his own experiences and the athletes he has trained, about the hardships and compromises needed to be the best.

It’s against the backdrop of the book that I find myself perturbed by the growing meme of “quiet quitting.” I felt compelled to write about it because of the meme’s potentially troubling implications for both individuals who practice it and society at large. Quiet quitting is not only antithetical to Grover’s winning mentality but also, in my view, to how ordinary people actually achieve success in their professional and personal lives.

What is quiet quitting anyway?

It’s a new way of describing an old idea. It encourages people not to quit their jobs but to do the bare minimum at work. In other words, the message is: don’t go above and beyond the call of duty. The root of this cultural fad is a Tik Tok video popularized by Gen Z (those currently in the age range 9 to 24), although it’s gaining wider societal traction.

At some level, I get it. The pandemic has been hard for many of us—and especially Gen Z-ers. They’ve lost years of in-person schooling and in-person job experience (often their first professional job out of university), not to mention experiencing prolonged periods of social isolation and a lifestyle that arguably is anti-human. We are, after all, social beings.

The workplace effects of this now two-and-a-half-year shock are profound. Without in-person interactions, many Gen Z-ers have missed out on early-career experiences that, traditionally, have shaped our professional lives.

To be sure, remote work has its benefits. It allows us to avoid punishing commutes and unproductive office distractions while providing greater flexibility over our day-to-day schedules. But there are drawbacks too.

The experiences you get from face-to-face interactions are hard to substitute via Zoom calls. For instance, it’s harder to build strong teams and workplace bonds when you’re not in the room together with your colleagues. It’s also harder to network professionally. But one of the biggest drawbacks of remote work is the impact on young people’s ability to observe and emulate effective behaviour and habits from their successful colleagues and mentors.

It’s no wonder why some Gen Z-ers are less attached to their workplaces and employers. Their apathy makes some sense.

At the same time, however, buying into the mantra of quiet quitting isn’t necessarily the answer. It can be corrosive to our workplace cultures and national economic outcomes. Quiet quitting breeds complacency and stagnation at a time when we need more ambition in our society to improve our productivity, innovate, and solve major social, environmental, and economic challenges.

Now, I don’t think Grover’s winning approach is the path for everyone. We shouldn’t all be workaholics who sacrifice everything for our jobs and toss away our personal goals as parents, spouses, friends, and community members. That’s of course unhealthy and unsustainable. Besides, not everyone wants—or is willing to put in the work—to become the next MJ in their chosen field.

But a little more drive and ambition would help us reach our individual potential and, collectively, the benefits would include more innovation, dynamism, and greater economic progress. At our core, we all want to grow and make a better life for our families. A stagnation philosophy kills that impulse.

There’s much to learn from Grover’s observations about peak performance, even if workplace supremacy isn’t your thing. If your goal is more ordinary workplace success, it’s hard to get around putting in the work and making some trade-offs along the way. The trade-offs can be calculated and within reason; you don’t have to risk everything else you care about. The point is that trade-offs are effectively a short-term struggle for long-term success. The quiet quitting mantra espouses the exact opposite philosophy.

Beyond the harshness and extremism, Grover’s book is filled with rich advice on how we can perform better. Take, for instance, the notion of constant learning in chasing the next win. As Grover notes: “Winning requires you to learn, question what you learned, and then learn more. You have to be willing to challenge what you’ve been taught, and learn it again with a different perspective.” This is just good advice if you believe in continuous self-improvement.

Or take the distinction he makes between fear and doubt. Fear is natural while doubt is in the mind. “Fear heightens your awareness; it makes you alert. Doubt is the opposite; it slows you down and paralyzes your thinking,” writes Grover. The antidote to doubt is confidence. You need to bet on yourself.

A last insight I’ll mention here is Grover’s idea of leveraging our “dark side”—the feelings of anger, fear, and inadequacy from previous experiences. It’s about using negative emotions (for example, stemming from the time someone told us we weren’t good enough) to fuel greater focus and performance. When harnessed productively, our dark side can be an energy spark, instead of a drain, in our pursuits.

More broadly, for Gen Z-ers thinking about quiet quitting, here’s some additional unsolicited advice.

Ideally, you want to start by finding a job that you enjoy doing and where you see an opportunity for long-term progress. There’s nothing worse than getting up in the morning to do something you hate. Passion makes the road to success slightly more tolerable. Try to limit staying at a job you hate; lingering with a quiet quitting mindset can be worse than quitting altogether.

Assuming you’re in a position you enjoy, adopt a strong work ethic and develop what Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck calls a growth mindset. View challenges as opportunities. When no one else wants to do a task or take on a project, put your hand up. In other words, do the things others are unwilling to do. That’s how you grow, develop, and become indispensable. Ultimately, going above and beyond will increase your promotional opportunities and career prospects.

Or don’t. If you buy into the quiet quitting meme, just realize that the trade-off is complacency and a lack of growth. Practice a stagnation philosophy at your own peril and practice it with realistic expectations. No one is entitled to success. You can’t expect to succeed if you’re not willing to put in the work and make some trade-offs along the way.

Recommended for You

Adam Zivo: No Dr. Bonnie Henry, drug prohibition is not ‘white supremacy’

DeepDive: Two-parent families: why they’re so important—and why there’s cause for concern in Canada

Patrick Luciani: Does liberalism make us better people?

Alicia Planincic: Want to regain support for immigration? Prioritize economic immigrants once again