Sixty years ago this month, the world stared into the abyss. The Soviet Union was caught trying to sneak nuclear-tipped missiles into Cuba. In response, over one hundred thousand U.S. troops were prepared to invade Cuba, while 3000 nuclear missiles were aimed at the USSR.

The situation was so tense that experts estimated a one-third to a fifty-fifty chance of a nuclear war killing 100 million Americans and the same number of Soviets. Moscow ordered Soviet soldiers at home and abroad to put on their uniforms. When death came, honour demanded that they die as heroes. Millions in other countries would have perished in the crossfire. This was the most dangerous moment in world history. But Armageddon didn’t happen. “We lucked out,” said Robert McNamara, former U.S. Secretary of Defense. Think of it as a black swan event in reverse, one that didn’t bring disaster.

The outline of the story is well-known. In early October 1962, American photos of Cuba—before satellites—showed Soviet nuclear short and long-range missiles just 90 miles off the U.S. coast. The Americans became suspicious when they discovered soccer fields in their photos, knowing that Cubans play baseball, not soccer. It turned out that over 40,000 Soviet soldiers in Cuba had entered the country disguised as tourists and labourers. There were now over 100 tactical nuclear weapons throughout the country and nuclear-armed ballistic missiles that could strike deep into North America. It was later discovered that local Soviet commanders had the power to launch these weapons without clearance from Moscow. This only heightened the danger.

President John F. Kennedy was given two options by his advisors, accept the weapons in Cuba and live with the danger, or initiate a complete air and ground invasion. Kennedy did neither but imposed the less dangerous option of a naval blockade around the island, freezing dozens of Soviet ships at sea from delivering more equipment. Either through diplomacy or war, Kennedy was determined to get the nukes out of Cuba. To show the Americans meant business, Kennedy publicly confronted the Soviets showing the photos of the rockets, and demanded their immediate withdrawal. He also raised the nuclear alert to its highest level at DEFCON 2, putting American B52s on alert, the core of the U.S. nuclear bomber fleet.

In the 1960 election, Kennedy campaigned on the theme that the U.S. was falling behind in nuclear weapons technology. This wasn’t true. The Russians had only about 30 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs)“ICBM, in full intercontinental ballistic missile, Land-based, nuclear-armed ballistic missile with a range of more than 3,500 miles (5,600 km). Only the United States, Russia, and China field land-based missiles of this range. The first ICBMs were deployed by the Soviet Union in 1958; the United States followed the next year and China some 20 years later.” https://www.britannica.com/technology/ICBM and accurate intermediate missiles but no way to deliver them to targets in the U.S. Putting them into Cuba was the solution. The U.S. had 200 ICBMs, dozens of submarines to launch missiles, and hundreds of intermediate missiles throughout Europe and Turkey that could reach Soviet targets.

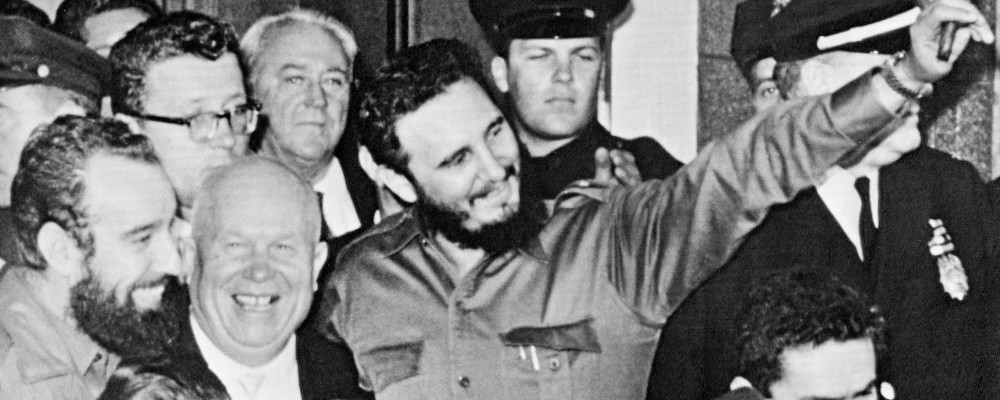

After a standoff of thirteen agonizing days in late October, the Soviets blinked. They realized they had blundered.

Premier Nikita Khrushchev wrote to President Kennedy, agreeing to remove the missiles in exchange for lifting the blockade and guaranteeing that the U.S. would not invade Cuba. The Americans agreed. Realizing they needed more to save face, Moscow upped their demands in a second Khrushchev letter, insisting that the U.S. also remove their missiles in Turkey. Kennedy accepted but asked that this side agreement be kept secret.

The story has another dimension little known to the world. There was a third letter, not written by Moscow to Washington D.C. but from Fidel Castro to Khrushchev. Castro was left out of the direct negotiations between the two superpowers, enraging the Cuban leader. Castro was convinced that despite the American assurances, he believed an American invasion was imminent.

Castro’s letter said that if the “imperialists” invaded, “then that would be the moment to eliminate this danger forever…however harsh and terrible the solution.” In other words, the Soviet Union should retaliate immediately with nuclear weapons now in Cuba.

Castro stressed that the Cuban people were willing “to confront aggression heroically” and that the “people’s morale is extremely high.” A boastful assumption, given that the Cuban people were never informed. It’s hard to believe that Moscow gave Castro’s letter any serious thought. They must have realized they were dealing with a madman. Cuban missiles were there to protect the Soviet Union, not Cubans.

The Cuban missile crisis has been a subject of intense study by decision-makers and political scientists. President Biden seems to have learned the lessons. The U.S. reaction to Putin’s recent escalation is directly out of Kennedy’s playbook that weakness only emboldens aggressors.

The Castro letter is little known outside those who study such matters. That’s a pity because Canada, which has been a generous supporter of the Cuban people for over half a century, deserves to know that Cuba’s dictatorial leaders were willing to sacrifice the lives of millions to fulfill the dreams of a now-defunct political philosophy.

Recommended for You

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by

David Mulroney: Foreign Minister Joly, Xi Jinping’s China doesn’t do ‘dialogue’

J.L. Granatstein: Trudeau’s submarine charade