Today the country is taking a statutory holiday in honour of Queen Victoria, the figure perhaps most emblematic of colonial empire. It requires a bit of cognitive dissonance given that colonialism itself has an almost uniformly bad reputation. Canadians can enjoy the day off as long as they don’t think deeply about the underlying purpose.

Yet depth and nuance is justified in thinking about the British Empire. Its legacy—including its ill effects—deserve to be placed in a larger context.

Let’s start with a basic definition and brief history. An empire is a single state that contains a variety of peoples, one of which is dominant. As a form of political organization, it has been around for millennia and has appeared on every continent.

The Assyrians were doing empire in the Middle East over four thousand years ago. They were followed by the Egyptians, the Babylonians, and the Persians. In the sixth century BC the Carthaginians established a series of colonies around the Mediterranean. Then came the Athenians, followed by the Romans, and after them the Byzantine rump.

Empire first appeared in China in the third century BC and, despite periodic collapses, still survives today. From the seventh century on Muslim Arabs invaded east as far as Afghanistan and west as far as central France.

In the 15th century empire proved very popular: the Ottomans were doing it in Asia Minor, the Mughals in the Indian subcontinent, the Incas in South America, and the Aztecs in Mesoamerica.

In North America, the Iroquois reconquered the St Lawrence Valley in the late 1600s before expanding westward as far as present-day Illinois. Shortly afterward the Comanche began extending their imperial sway over much of what is now Texas, eventually running what one historian has called “a vast slave economy.”

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic to the south the Asante were expanding their control in West Africa, and in the 1820s King Shaka led the Zulus in scattering other South African peoples to several of the four winds.

Set in this global historical context, the emergence of European empires from the 15th century onwards is entirely unremarkable. The Portuguese were first off the mark, followed by the Spanish, and then, in the 16th century, by the Dutch, the French, and the English. The Scots attempted (in vain) to join their ranks in the 1690s and the Russians did so in the 1700s.

What is very remarkable, therefore, is that the present controversy about empire and colonization shows no interest at all in any of the non-European empires, past or present. European empires are its sole concern, and of these, above all others, the English—or, as it became after the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707, the British—one.

The reason for this focus is that the real target of today’s anti-imperialists is the West or, more precisely, the Anglo-American liberal world order that has prevailed since 1945. This order is held responsible for the economic and political woes of what has become known as the “Global South.” Allegedly, it continues to express the characteristic “white supremacism” and “racism” of the old European empires, displaying arrogant, ignorant disdain for non-Western cultures, thereby humiliating non-white peoples.

The British Empire is a proxy for the West. The phrase “Colonialism and slavery” is often used to sum it up, as if the two things were identical. And it is common to hear British colonialism likened to Nazism—as Kehinde Andrews did recently in a panel discussion at the University of Cambridge. Indeed, as far back as 1999 a collective of Canadian authors were claiming that “Queen Elizabeth … Queen Victoria … were the ‘Adolf Hitlers’ of their day.”

Like any longstanding state, empires invariably presided over tragic evils and grave injustices. The British one was no exception. During its three-hundred-year life, the British Empire entered the following items into the debit column of the imperial ledger: brutal slavery, the (inadvertent) epidemic spread of devastating disease, economic and social disruption, the unjust displacement of natives by settlers, failures of colonial government to prevent settler abuse and famine, elements of racial alienation and racist contempt, policies and practices of needlessly wholesale cultural suppression, miscarriages of justice, instances of unjustifiable military aggression and the indiscriminate and disproportionate use of force, and the failure to admit native talent to the higher echelons of colonial government on terms of equality quickly enough to forestall the build-up of nationalist resentment.

All that is lamentable.

Yet the imperial accounts contain a credit column, too. If the Empire initially presided over the slave trade and slavery, it was among the first states in the history of the world to renounce both in the name of a Christian conviction of basic human equality in the early 1800s. It then led endeavours to suppress them worldwide for a hundred and fifty years. The Empire also moderated the disruptive impact of inexorable Western modernity upon very unmodern societies, created regional peace by imposing an overarching imperial authority on multiple warring peoples, promoted a worldwide free market that gave native producers and entrepreneurs new economic opportunities, perforce involved representatives of native peoples in the lower levels of government, sought to relieve the plight of the rural poor and protect them against rapacious landlords, provided a civil service and judiciary that was generally and extraordinarily incorrupt, developed public infrastructure, made foreign investment attractive by reducing the risks through establishing political stability and the rule of law, disseminated modern agricultural methods and medicine, brought up three of the most prosperous and liberal states now on earth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and gave birth to two more (the United States and Israel).

So, the Empire did good as well as evil. But did it do more good than evil? Those who advocate reparations for colonial evils think that it did more evil than good—but they assert it, without arguing their case. They don’t argue their case because it can’t be easily argued. Nor can the counter-case. This is because the goods and evils that the Empire caused, intentionally or not, are of such different kinds that they cannot be measured against one another. They are incommensurable. How much chalk is worth so much cheese? How much racism is worth so much immunization against disease? How many unjustly killed people are worth the blessings of imperially imposed peace? How much humanitarian anti-slavery would make up for the evils of slavery? To ask these questions is immediately to expose their absurdity.

Given that all kinds of human rule produce a mixture of good and evil—even the Nazis built autobahns in Germany and the Fascists made the trains run on time in Italy—does it follow, therefore, that the moral difference between them is only a matter of degree, and that we cannot judge any of them to be, all things considered, wrong? No, it does not. We can try to discern central values or principles that were consistently expressed and concordant goals that were earnestly pursued and realized, more or less. If these values, principles, and goals were gravely evil and immoral, we can then say that the rule was systemically unjust. And if it was not systemically unjust, then we can say that it was systemically just, more or less.

The most obvious candidate for a systemically unjust regime is that of the Nazis in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. Dominated by the mind of one man, its view of the world was violently racist and its aggressive, expansionist nationalism unburdened by moral scruple. The death factories devoted to “processing” millions of Jews in the midst of the exigencies of war were not incidental to the regime; they expressed its resolute, crazed heart.

It is no accident that the contemporary enemies of European and, especially, British colonialism try to assimilate or identify it with Nazism. For then we can all be sure that it was basically, essentially evil—notwithstanding all the colonial building of bridges and railways. Hence the claims of colonial “genocide” in 1820s Tasmania and 1890s Matabeleland, of racist callousness towards the starving First Nations on the western plains of Canada in the 1880s, of “crimes against humanity” in Benin in 1897, and of “concentration camps” in South Africa in the 1900s and Kenya in the 1950s.

However, as my book Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning shows, it is entirely inappropriate to liken the British Empire to Nazism. Nor was it essentially racist or disproportionately violent. Nor, with due respect to Marxist critics, was it essentially exploitative. From the early decades of the 19th century, its natural, innocent concerns to promote trade and maintain strategic advantage were increasingly supplemented and tempered by Christian humanitarianism, a commitment to public service, and a liberal vision of political life. As Margery Perham wrote in 1961 with regard to Africa:

No record can ever be made of all that was done, good, bad and indifferent, by Britain in her dozen or more African territories during the brief years of her tenure. The mosaic is too vast for its pattern to be seen at one time or from one viewpoint, and we are always brought back to the question of standards by which to judge Britain’s record. There can be no doubt that, if the standard is to be the interests of the ruled, these have steadily counted for more as the period of empire continued. The existence of informed liberal opinion, the publicity of debate, the use of commissions of inquiry to probe every serious problem and grave event, all helped to this end. The African colonies, as the latest acquisitions, have greatly benefited from this progression in virtue.

Perham’s point about the important role played by liberal traditions and institutions of free speech and political criticism was amplified by Lewis Gann and Peter Duignan when they observed that the imperial system in general had “a built-in capacity for self-criticism”:

Future historians will necessarily draw on the material accumulated by … commissions of inquiry, parliamentary debates, metropolitan blue books, and similar records which formed part of a self-corrective mechanism of a type unknown to earlier Matabele, Somali, or Arab conquerors; they played an important part in putting a stop to imperial abuses.

Also included in the liberal political vision was the good of self-government. As early as 1820 all three Scottish governors of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras recognized that British rule in India could not be permanent and should aim to enable the natives to govern themselves decently and then withdraw with a good grace. One of them, Sir John Malcolm, wrote in 1823:

Let us, therefore, calmly proceed on a course of gradual improvement: and when our rule ceases, for cease it must (though probably at a remote period), as the natural consequence of our success in the diffusion of knowledge, we shall as a nation have the proud boast that we have preferred the civilisation to the continued subjection of India.

By 1930 Canada, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand had become effectively self-governing. From 1919 the British were committed to widening Indian participation in government en route to the same political autonomy. The vision of the Empire evolving into a voluntary Commonwealth of Nations was already in play.

The British Empire contained both good and evil. It was not essentially evil. It showed itself capable of learning from its mistakes and correcting itself. And from the end of the 18th century its humanitarian and liberal commitments grew ever stronger, reaching their climax between May 1940 and June 1941, when the Empire offered the only military resistance (alongside Greece) to the massively murderous racist regime in Nazi Germany. For that reason, it is possible to stumble across the tragic war graves of young Canadians far from home on the southwestern slope of Mount Etna in Sicily. And if we look carefully, we may find the one belonging to a lad from Winnipeg, whose laconic headstone bears the admirable epitaph, “Anti-fascist.”

Recommended for You

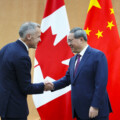

‘An approach that lacks principles’: The Roundtable on Canada’s confusing China reset and the lack of scrutiny on Carney

Why I flew to Israel for the hostage release

Kick a robot for me

Canada, the duct-tape nation