Recent developments have led to emerging questions about the sources of shared Canadian citizenship and common identity. As our country becomes more heterogenous—and possibly polarized—, there’s a need for some familiar socio-cultural markers or things that we do together.

Hockey has historically been one of those things. Paul Henderson’s winning goal in the 1972 Summit Series or Sidney Crosby’s “golden goal” at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics or even simply the shared experience of playing street and pond hockey have been sources of social cohesion and national unity.

Recent polling suggests that the sport remains a crucial part of how Canadians conceive of their country and their relationship to one another. Ask most Canadians what they most associate with Canada, and often their answer is hockey. In 2021, for instance, Angus Reid reported that 62 percent of Canadians felt a connection to hockey, whether through playing it, watching it, or being involved. According to a 2022 Environics survey, 74 percent of respondents felt hockey was important to Canadian identity, with more support amongst those from racialized backgrounds than not.

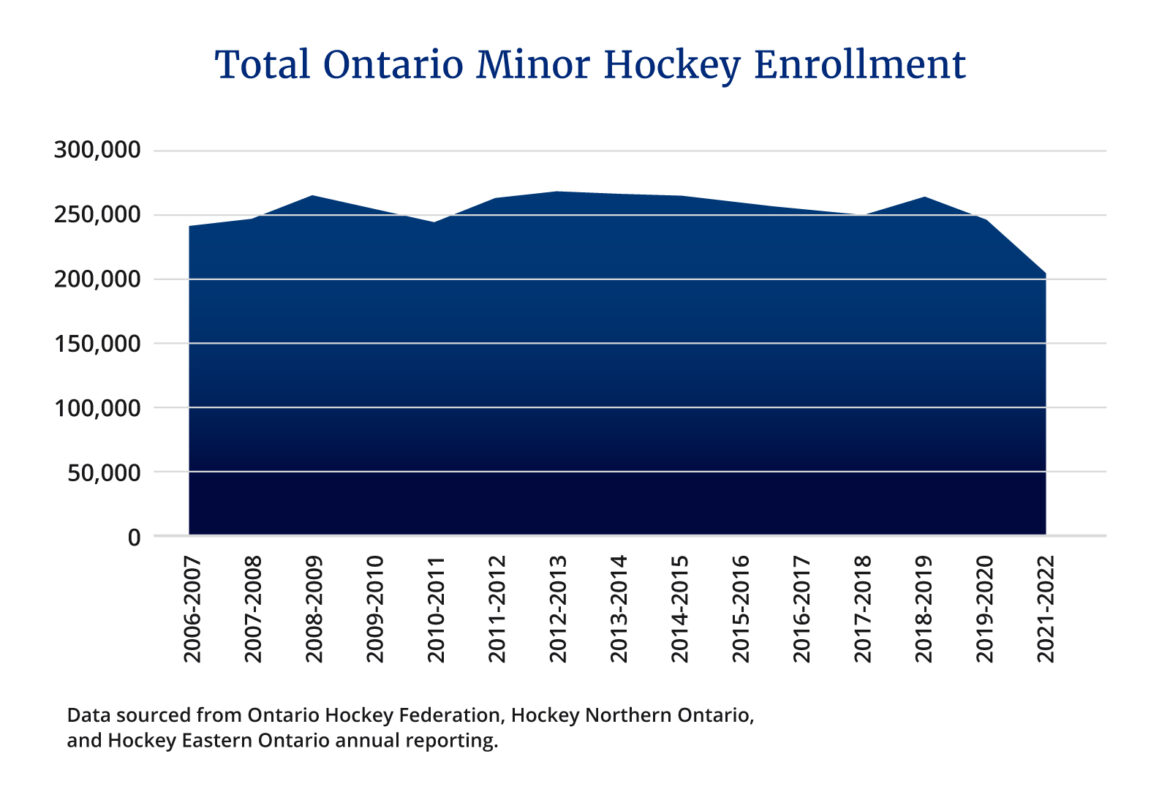

Yet notwithstanding hockey’s ongoing cultural relevance (or perceived cultural relevance), its role as a common source of experience and identity is diminishing. Take Ontario for instance. Across the province’s three main minor hockey organizations, enrollment is decreasing. Between 2006-07 and 2021-22, the number of Ontario kids enrolled in hockey fell by nearly 20 percent (241,500 in 2006-07 to 203,100 in 2021-22) even though the total number of kids under age 17 was nearly identical at 2.77 million (see figure 1).

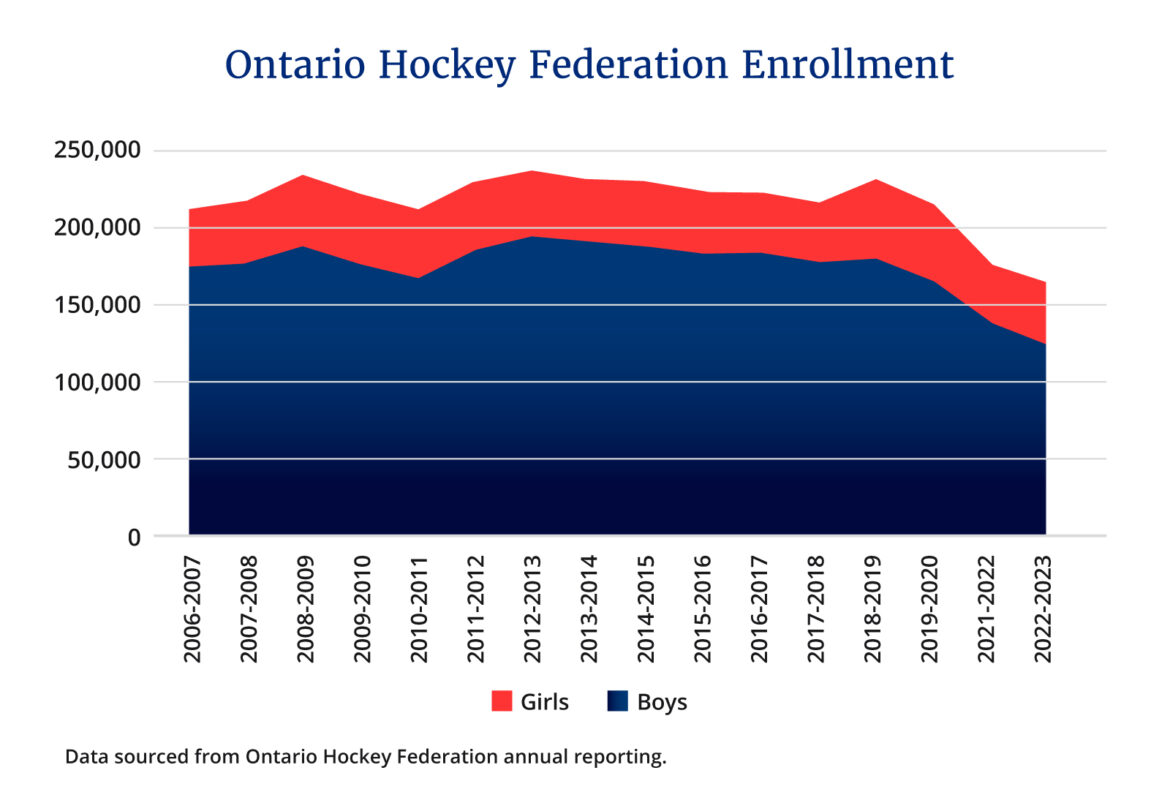

These secular trends seem to have been accelerated by COVID. Previously growth was flat. Now it is declining across the province. Only one organization, the Ontario Hockey Federation (roughly the area inside Kingston-Windsor-North Bay, and Thunder Bay) has reported its enrollment numbers for 2022-23. Figure 2 shows a year-over-year decline of nearly 8 percent (175,764 kids in 2021-22 to 163,671 in 2022-23).

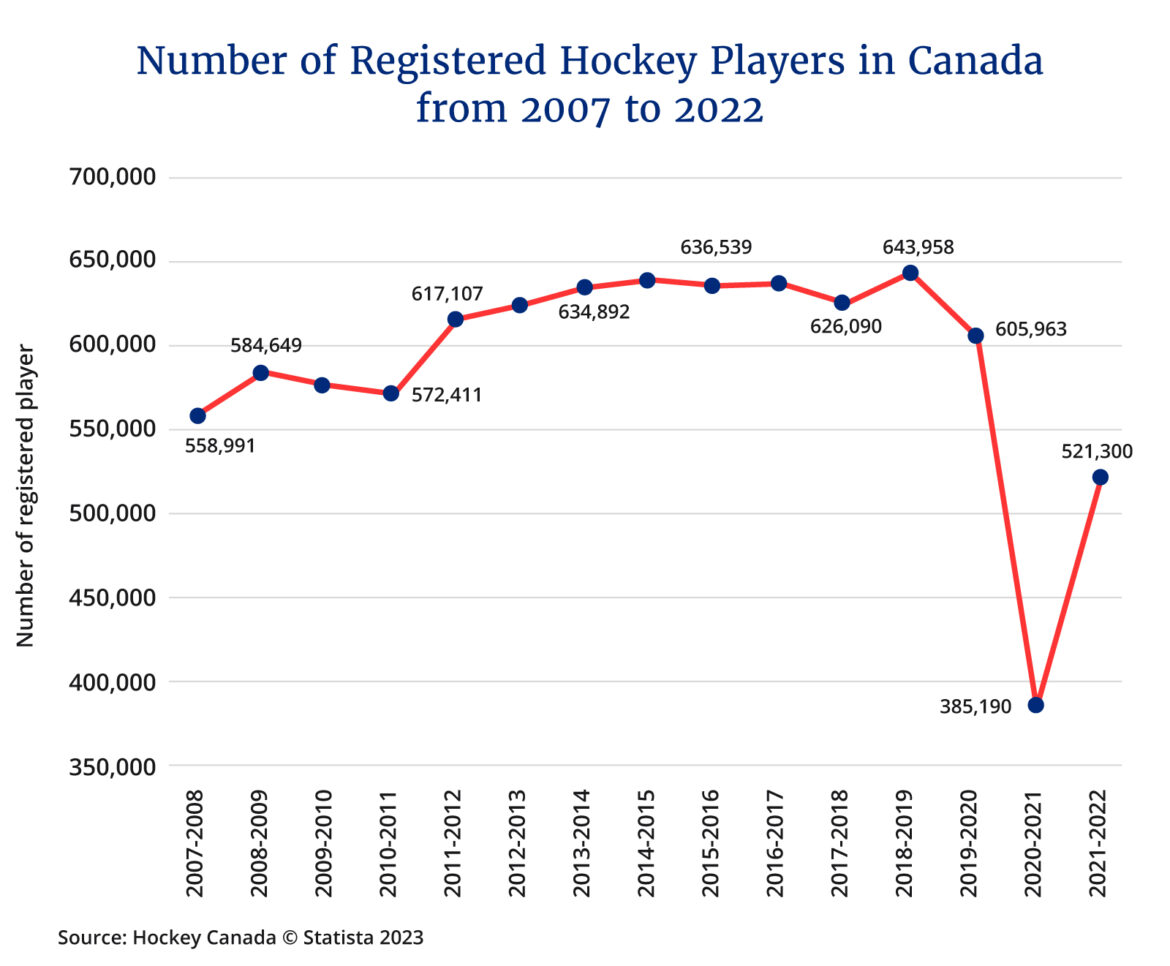

These trends aren’t limited to Ontario either. Across the country, minor hockey enrollment has not recovered to pre-COVID levels. Figure 3 shows that the number of registered minor hockey players is still about 15 percent less than it was prior to the pandemic, and is now below where it was in 2007-08.

I believe these trends shouldn’t merely be of concern to hockey organizations. Canadian policymakers should also take notice. It represents the diminishment of a source of shared experience and common identity at a time when one is so greatly needed.

As Ken Dryden wrote in his popular book, The Game: “There is no sport in the United States that means the same as hockey means to Canada.” He’s right. The loss of hockey isn’t merely about lost recreation. It represents the loss of something core to how we think about the country and our relationship to one another.

It prompts the question: what is going on?

A major factor is cost. It is no secret that hockey has become a high-priced sport to play, with registration fees reaching into the thousands of dollars for competitive levels and the high hundreds for more relaxed house leagues. As Wayne Simmonds, a 17-year NHL veteran, himself from Scarborough and whose family held BBQs to fundraise for his annual hockey costs, has said: “Obviously I believe it’s the best game in the world, but I don’t think a lot of people are able to experience it because of the costs.”

In Mississauga, the Lorne Park Hockey Association charges $825 for a child under 10 in house league. If anything, this is, in relative terms, cheap. In 2019, Scotiabank reported that nearly 60 percent of hockey parents spent more than $5,000 per year on hockey-related expenses. Costs for skates, sticks, and equipment add up quickly. Account for the costs of gas to and from games, tournament fees, and overnight stays, not to mention opportunity costs, and it becomes cost-prohibitive—especially when the median after-tax household income is $73,000.

To their credit, minor leagues have recognized this and have programs to help defray the costs. But the major expenses cannot be defrayed by the leagues alone. The Greater Toronto Hockey League’s 2023-24 registration shows that 90 percent of annual budgeted expenses for competitive teams will go towards paying for the cost of the ice alone.

Here’s where there is a role for public policy. The Ontario government helps to address this issue by using Infrastructure Ontario (or the new Ontario Infrastructure Bank) to provide cut-rate loans to municipalities to build rinks in their communities. The province could also explore how to provide funds for renovations using a competitive process like a reverse auction, where municipalities could bid down the price of renovations. Using a tiered system grouped by relative size/income could help to smooth out imbalances and ensure that every location in the province is competitive. The funds could be sourced from dedicated proceeds from online sports betting, allocated on either a provincial priority or population basis. This would help solidify the social licence of online sports, as well as ensure that the benefits the tax revenues generate are clearly connected to the public.

Alternatively, since it is easier to build new rinks where people are not yet living, the Provincial Policy Statement could be revised to add emphasis that as-yet undeveloped areas are strongly encouraged to have new multi-surface rinks (which could be built using those cut-rate loans).

Underrepresentation and cultural siloing represent a threat to hockey’s unifying benefits that may be as big as the rising cost. Despite widespread support in immigrant and racialized communities, there is a serious challenge with getting more from these communities into the game. In the past three years, for instance, 67 percent of new players in the Ontario Hockey Federation have been white, with the next two largest groups being “Prefer not to say” and “Unknown”. In fact, the only self-declared ethnic groups to break 2 percent were Indigenous (2.23 percent) and Chinese (2.03 percent). For one of the most diverse areas in Canada, this is a disappointing statistic and a sign that more progress is necessary.

Making hockey more reflective of the population as a whole will require a concerted social effort, which can be assisted by government. The federal government, always searching for ways to connect Ottawa to local voters and their communities, could look to expand programs aimed at new Canadians and those wanting to try the game from Hockey Canada.

While Ottawa may be hesitant to fund local sports, the unique national reach of hockey—what economists would call its “positive externalities”—justify public dollars, particularly in a period in which social cohesion and national unity are under strain. Similarly continued support from equipment donation networks, local volunteer groups, and corporations who are interested in developing future consumers, are all going to be needed to break through the barriers to play.

Hockey’s continued relevance as a sport that transcends recreation and reflects far deeper notions of shared experience and common identity is both more important than ever and less certain than ever. There’s a role for both civil society and government to expand access to the game and renew its place in modern Canadian culture.

Recommended for You

Kelden Formosa: A pope for the once and future church

Kirk LaPointe: Is this the year Canada (finally) brings the Stanley Cup home?

‘Atheists are wrong’: Ross Douthat makes the case for why everyone should be religious

Patrick Luciani: The death of reason in the age of Trump