There has been no shortage of dramatic warnings about the consequences of not extending the Canada Emergency Business Account (CEBA) loan repayment deadline.

“Fears of bankruptcy as small businesses stare down federal CEBA loan deadline,” read one headline. Another warned restaurants have “limited options to avoid bankruptcy”, while Restaurants Canada suggests one in five restaurants holding an emergency loan is teetering on the edge of closure.

Extending the deadline for repaying interest-free loans granted to businesses during the pandemic by another year wouldn’t be cheap. The Parliamentary Budget Office estimates it would cost the federal government $900 million. But proponents argue it is necessary to prevent numerous businesses from shutting down.

While business failures are indeed on the rise, trying to stop this might not only be counterproductive but might also miss an even more concerning trend.

Rising bankruptcies

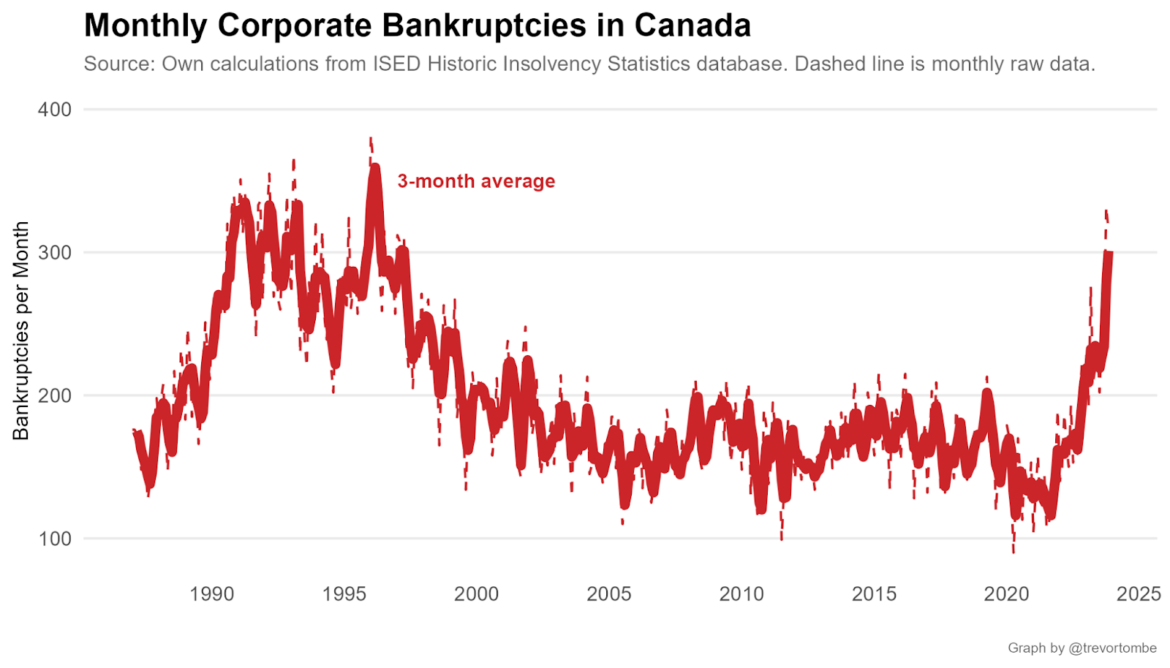

First, some data: the latest statistics show clearly that bankruptcies have soared.

The current figures are nearly double the average number of bankruptcies in the years preceding the pandemic. This translates to approximately a dozen businesses declaring bankruptcy every day. And corporate bankruptcies are at levels not seen since the 1990s.

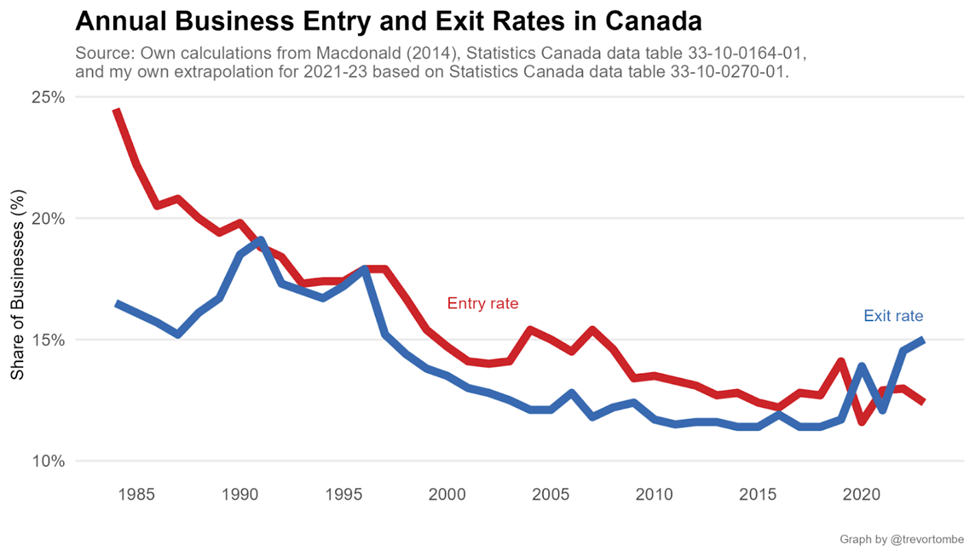

It’s not just bankruptcies that are up. Businesses often close for a variety of other reasons. Most bankruptcies result in a business exiting the market, of course, but most exits are not bankruptcies. And a broader measure of business exit shows a similarly sharp rise.

I estimate that approximately 2 percent of all businesses are now closing their doors each month. This rate is one-third higher than the 1.5 percent of businesses that were closing monthly earlier in 2021. On an annual basis, firms are shutting down at a higher rate than at any point in thirty years.

For many, these are concerning statistics. But this isn’t all bad news.

The benefits of firm exits

Exiting firms tend to be less productive and exhibit lower productivity growth over time compared to their counterparts that remain in operation. Of the businesses that closed over the roughly two decades prior to the pandemic, for example, nearly 70 percent of exiting firms were in the bottom one-third of Canadian firms in terms of labour productivity. They’re also smaller and less profitable.

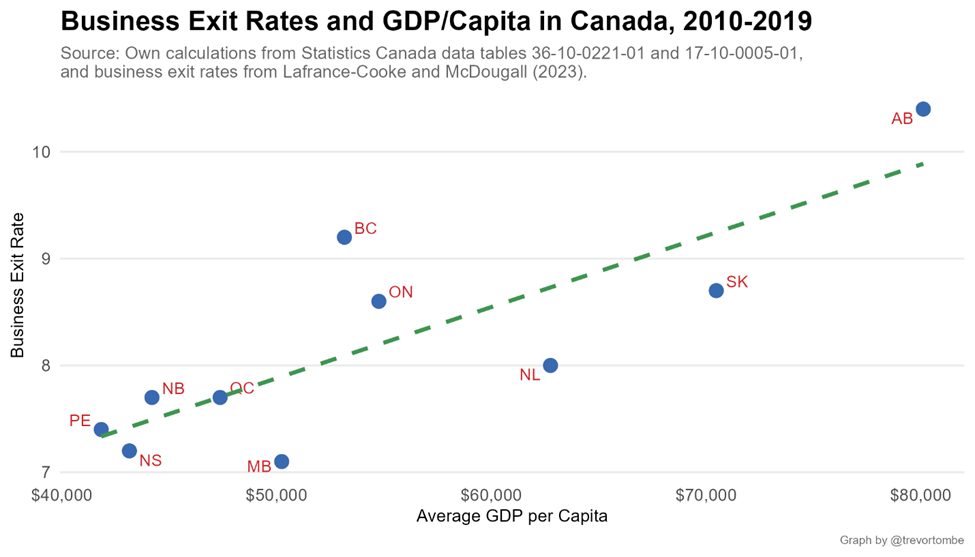

Simply put, firms that are unable to adapt, innovate, or improve their productivity are more likely to face challenges that could lead them to close their doors. A dynamic and growing economy requires nothing less. Machinery, labour, buildings, and so on, can be better used elsewhere by other, more productive firms. This is perhaps partly why the strongest provincial economies in Canada consistently have higher exit rates.

It’s not easy on the owners of the failing firm, of course, and there are real costs to such closures. And given the mounting strain from rising input costs, rapidly tightening credit conditions, and increasing economic uncertainty, some might argue that closures go beyond what the normal process of creative destruction involves.

But efforts to artificially prevent failures, such as increasing the generosity of government support programs or extending emergency loan deadlines, could easily do more harm than good.

A more concerning trend

So instead of focusing on exits, we should consider an even more concerning trend buried in the data: the rate of new business creation in Canada is way (way!) down.

Using some historical data and the latest available monthly information from Statistics Canada, I estimate that the pace of firm entry is nearing its all-time low. At barely more than 12 percent for the year, this is less than half the rate of the mid-1980s, and far below the rate of firm exit.

Except for 2020, we have never seen the pace of entry lag so far behind business exits.

Canada’s economy seems to have become far less dynamic. That’s a problem.

This matters for more than just our lagging productivity performance. The Competition Bureau, for example, recently highlighted these measures of falling dynamism as potentially concerning since existing firms will feel less pressure from new entrants. This could increase their market power and raise prices for Canadians.

Rather than trying to prevent or delay business failures, policymakers should focus on fostering new business creation. This shouldn’t be done artificially through subsidies, but rather by removing barriers that hinder startups in the first place. This means easing regulatory burdens, liberalizing foreign investment, reforming business taxes, improving access to credit, and more.

Entrepreneurship and innovation are vital for the long-term health of the economy. Business failures, while often seen in a negative light, are an essential part of this process. They make room for new ideas and release valuable resources to be better used by others.

The real challenge lies not in the businesses closing their doors, but in the dwindling number of new businesses opening up.

Recommended for You

Why we are launching NewsBox for The Hub’s paid subscribers

8 things to watch for as Conservatives gather in Calgary for party convention

Carney is right about Canada’s place in the world—but words are not enough

Stop calling Mark Carney a closet conservative