It’s been well over a year now since Trudeau’s child-care policy has taken effect in most provinces across the country. Naturally each province, through negotiations with the federal government, has approached its implementation of the program slightly differently.

The program promised three definitive outcomes: quality (a subjective measure, but one worth unpacking), accessibility (i.e. more spaces), and affordability (i.e. less expensive spaces).

Quality

To start with the most nuanced, let’s consider quality. In order to measure the quality of a program, one first needs to understand the policy objective that the program aims to accomplish.

In reality, there are two quite different schools of thought when it comes to this area of policy. Simply put, you might call the first “child care” and the second “early childhood education.” In most of the country, these terms have become seemingly synonymous. In fact, we refer to licensed staff at child-care centres as “early childhood educators.”

So what’s the difference? Well, as the name implies, child care is for the purpose of having someone care for your child so that you might go to work. You might think of this similarly to hiring a babysitter while you’re out at night. A responsible adult needs to be present to ensure your child (or children) is safe. Put differently, the beneficiary of child care is not the child, but rather the parent.

Whereas early childhood education is for the purpose of educating our children. Decades of research support the idea that a strong foundation in early childhood education is one of the biggest determinants of future success. In this context, the beneficiary of early childhood education is clearly the child.

Although it’s plausible to combine child care with early childhood education, it’s important to clarify which outcome a set of policies intends to solve for. Are we designing a system to provide what amounts to institutionalised babysitting for parents, or are we designing a system that educates our kids and sets them up for long-term success?

Where does the Trudeau government’s plan land on this question? Has it designed a policy of child care or of early childhood education?

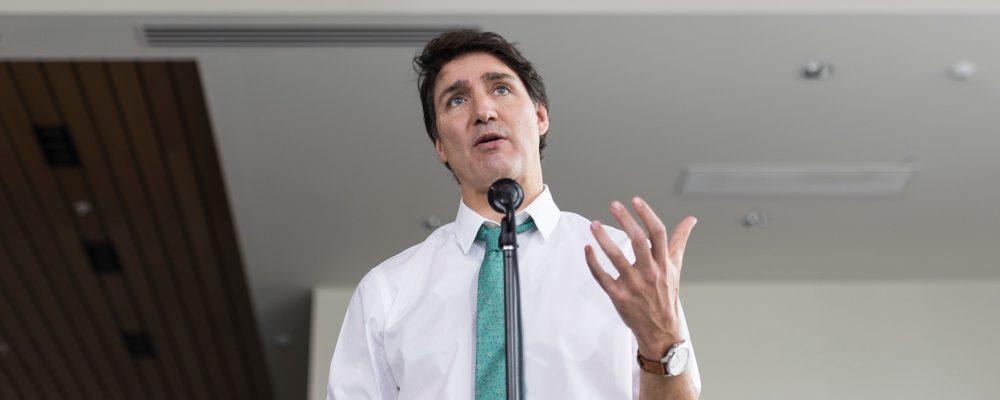

One doesn’t have to look much further than a regular media appearance of the prime minister or the finance minister to hear them cite the increase in women’s participation in the workforce as the primary measure of success of their child-care policy. The problem, as discussed above, is that this policy goal can be at odds with one focused on child outcomes. The experience from Quebec for instance certainly signals a tension here.

Accessibility

This measure of success is quite easy to measure. Have the number of available spaces at child-care centres increased or decreased as a percentage of the relevant population of children? A slightly more nuanced analysis would also consider the geographic distribution of those available spaces and whether they are in fact accessible to all socioeconomic groups equally. On the latter point, Rahim Mohamed covered this in a great piece last year for The Hub.

The more superficial measure of accessibility should be quite easy to measure, although any recent and relevant national statistics are lacking. So instead, we can look at recent anecdotal headlines to get a sense of where the sentiment of operators in the industry is on the question of accessibility.

CBC News in Toronto recently covered a 100-year-old child-care centre with 175 spaces announcing its closure, citing the provincial subsidy program as the primary cause. Similarly in Alberta, “rolling closures” of child-care centres are expected across the province. In Saskatchewan (as in other provinces), the province is falling well behind its commitments of opening sufficient new spaces.

All in all, across the country the consistent story is that waitlists are increasing, staff shortages are getting more severe, and child-care centres are not able to make ends meet within the prescribed formulas of their respective provinces.

On accessibility, it’s hard to argue for anything but a failing grade.

Affordability

This term is often significantly misunderstood. Whether in the context of groceries, housing, or child care, it’s important to think of affordability as a relative measure. Put differently, a $10 gallon of milk can be extremely unaffordable to a low-income family on a tight budget, but not make a real dent in the budget of an upper middle-class household.

What’s perplexing about this policy is its emphasis on $10 per day as an arbitrary measure of affordability, rather than considering the means of the family benefiting from the program.

Are there families paying less for child care today than before the program existed? Yes.

Are families with the greatest need disproportionately benefiting from the program? No, and in fact early data is suggesting the opposite: higher-income families are disproportionately benefiting from the subsidy.

Anecdotally and statistically, we’re seeing evidence across the country of higher-income families (who historically have been able to afford market-rate child care within their budgets) get to the front of the line for access to the subsidy ahead of lower-income families who might not have put their children in child care historically.

Whether you agree with the designed intent of the policy or not, it’s hard to argue that the metric of affordability has been met. On the one hand, families who don’t need the subsidy (or at least not the full value of it) are benefiting more than they should, and on the other hand, many families who could benefit are still stuck on waitlists or can’t find child care that meets the unique demands of their schedules (e.g. nurses working night shifts, retail workers with unpredictable schedules, etc.).

On system-wide affordability, I give the program a failing grade.

Conservatives need to scrap this program

I’ll leave the political calculus of this opinion to others, but I’ll highlight that Andrea Mrozek lays out a pretty compelling case that this issue is not as one-sided among Canadians as you might think.

Whether under the leadership of a Poilievre-led federal government or simply when it comes time for a renegotiation with the provinces, conservative leaders at both levels of government need to push back against this misguided policy that is showing early and worrying signs of failure.

Our objective as conservatives should be twofold: firstly, a policy that promotes parental choice and flexibility, and secondly, a policy that prioritizes the well-being and development of children within early childhood.

Taken together, this would undoubtedly lead to a generous system of tax credits directed to families with young children (adjusted for income), coupled with regulatory reform agenda to open up a competitive industry of early childhood education options that’s ultimately ranked based on the quality of programming.

To conservative provincial ministers responsible for early childhood education, the challenge is yours to solve.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes