Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland unveiled a federal budget yesterday that she insisted will deliver “fairness for every generation.” The Trudeau government plans to spend $52.9 billion in the next five years. The deficit will sit at $39.8 billion this year, with a plan for it to drop to $20 billion by 2028. No path back to balance was projected.

While the suspected wealth tax or excess profit tax did not appear, the government will seek to gain $19.3 billion in revenue over the next five years through an increase in the capital gains tax for corporations and Canada’s highest earners. The Liberals also promised to build 3.9 million homes by 2031.

“There are some things in this budget that we fought for, that we spent time hearing from Canadians, and we forced this government to deliver,” said NDP leader Jagmeet Singh. He highlighted new protections for renters, a national school food program, and a promise of free birth control. He did not however say yet whether he would support the budget. His party has continued to keep the Liberals in power by supporting the now two-year-old confidence and supply agreement.

“This prime minister is not worth the cost,” said Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre. “This is the ninth deficit after the prime minister promised the budget would balance itself.” “This wasteful inflationary budget…is like a pyromaniac spraying gas on the inflationary fire that he lit,” he added.

The Hub has collected insights from some of our wise contributors to get their take on the budget that was.

Government, be serious

By William Robson, CEO, C.D. Howe Institute

Yesterday’s federal budget showed again—as if it were needed—that this government is not serious about public finances. It was late, given that the 2024/25 fiscal year started more than two weeks ago. It buried the numbers on revenue, expenses, deficit, and debt that ought to be upfront under 350-plus pages of spin. And while the numbers themselves look serious—relentlessly rising taxes and spending, chronic deficits, and interest eating ever more revenue—we have no reason to believe them.

Why would we? The government’s first projections for the current budget year of 2024/25 were in its 2019 fall economic statement. That statement showed federal spending of $421 billion in 2024/25. The government presented no budget at all in 2020—more evidence of unseriousness—and its 2020 fall statement removed some pension costs from the presentation—yet more evidence.

But if we add those pension costs back, the 2020 statement showed spending in 2024/25 at $429 billion. That was a small sign of bigger things to come. The 2021 fall statement projected 2024/25 spending at $465 billion. The 2022 fall statement said $505 billion. The 2023 fall statement said $522 billion. Yesterday’s budget shows 2024/25 spending at $538 billion—an eye-popping 28 percent more than what the government projected in 2019.

Are other projections in the 2024 budget any more believable? The main defence against further rises in the ratio of federal debt to GDP is additional revenue from higher capital gains taxes, the digital services tax and a global minimum tax. But, the digital services tax may never be implemented, and the legislation for the capital gains tax increases and the global minimum tax is not even written. Notwithstanding rhetoric about fairness for all generations, the likely outcome is bigger deficits and an even heavier debt load on the young.

Canadians need many things from future federal governments, and treating public finance as though it matters heads the list. Tax hikes, rising debt and interest charges—these threats to our already stagnating living standards would not exist if the government did not now plan to spend $117 billion more than it projected in 2019. We need governments that take budgets seriously.

A lazy, imprudent government unwilling to do the hard work

By Chris Ragan, director of the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University

Like all government budget documents, budget 2024 contains many small measures, and it would be easy to spend considerable time debating the merits of each one. Even in those cases where the basic idea is sound, the ultimate success of the policy depends on numerous details regarding design and implementation. We should never forget how many government policies never work as initially intended.

At the micro level, here are a few notable positives among the list of measures:

- An additional $400 million for the Housing Accelerator Fund, which is already aimed at making agreements with provinces and municipalities to fast-track the construction of new homes. In addition, $50 million is devoted to streamlining the process to recognize the credentials of new Canadians with skills in the construction trades. Together (with many other measures in the budget), these will help to unlock some of the supply-side obstacles to the building of new housing in Canada.

- The introduction of a $5 billion Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program to unlock access to financial capital for Indigenous communities so they can participate in the ownership of major natural resource projects. In addition, a suite of measures designed to improve the regulatory and permitting procedures for getting major projects completed. Together, these policies increase the likelihood that Canada will be able to effectively build the many clean-energy projects we will need in the coming years.

- The creation of the new Canada Disability Benefit will provide up to $2,400 per year to low-income persons with disabilities between the ages of 18 and 64. This is a great example of the federal government using its fiscal power in a targeted way to help Canadians who need it most.

On the negative side:

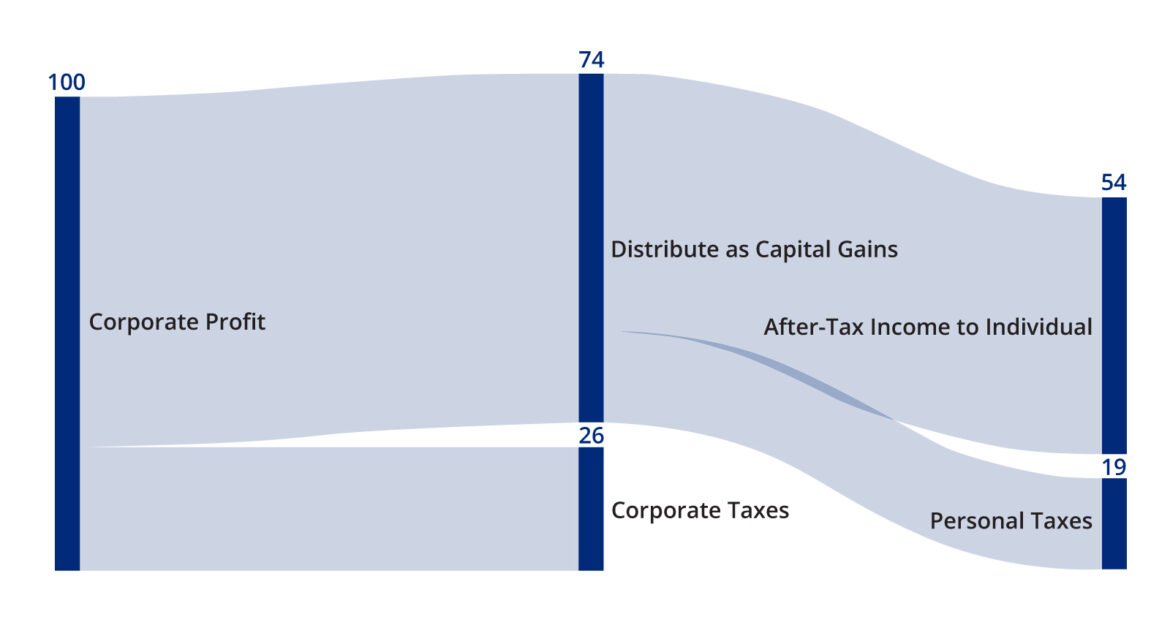

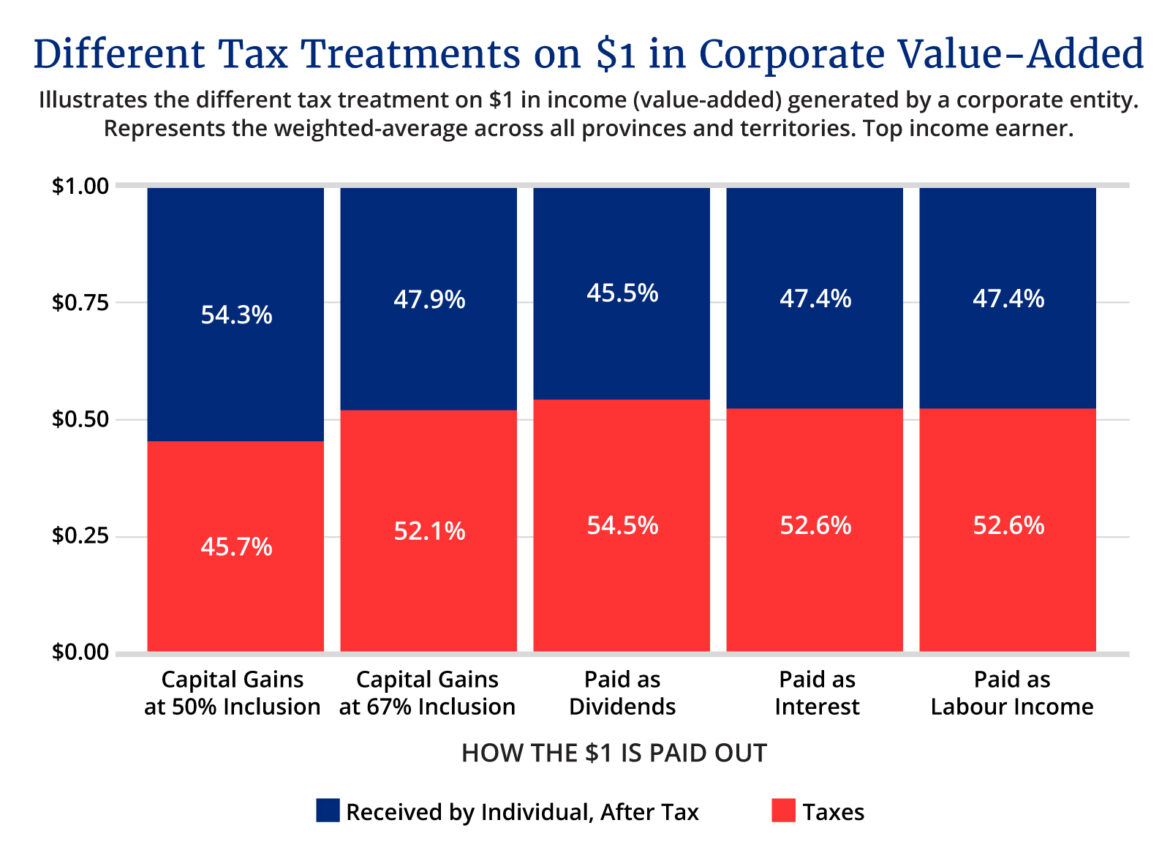

- A proposed increase to the capital-gains inclusion rate from 50 percent to 67 percent. For individuals, this new inclusion rate applies to all capital gains over $250,000 per year. For corporations it applies to all capital gains. The government notes that this increase will only be relevant for fewer than 1 percent of taxpaying individuals. The bigger concern is that for corporations this higher inclusion rate amounts to an increase in the effective corporate tax rate, and thus an additional disincentive for Canadian businesses to invest—at a time when Canada’s low investment rate is already a primary cause of our low productivity levels and growth rates.

Overall, though, the bigger negative for this budget is at the macro level in how the various measures all add up. The federal government is showing itself to be both lazy and imprudent in budget 2024. The laziness is reflected in the government’s unwillingness to cut spending on low-priority items as it introduces new spending programs. The obvious result is the need for larger budget deficits or higher taxes, or both.

The government states that it is continuing to find and redeploy $15.8 billion worth of spending over five years. But in an overall budget of $500 billion per year, $3 billion annually is a drop in the bucket. Instead of doing the more difficult work of seriously reviewing the many existing programs and cutting the ineffective ones, the government took the easier route of simply expanding its total spending and having ongoing budget deficits.

On the matter of deficits and public debt, the government is being imprudent by planning a path of budget deficits that is declining too slowly, with the result that the debt-to-GDP ratio is still likely to be at 40 percent five years from now. (The provincial governments combined have a debt-to-GDP ratio of about 32 percent.) The imprudence comes from putting too little weight on the future events that are likely to happen, even though we don’t know when.

Rising demands on our health-care systems driven by an aging population and public investments in energy transition are both certain to occur, and they will be expensive. Increases in military expenditures are also highly likely, and expensive if we are to fully honour our international commitments. Less certain but also expensive may be a recession, a financial crisis, or a pandemic—any of which could happen and demand a sudden increase in federal government spending and borrowing.

Being fiscally prudent would require getting the debt-to-GDP ratio down—much closer to 30 percent—in a few years so that we are prepared for the next fiscal emergency when it occurs. Displaying this prudence, in turn, would require the government to shake off its laziness and make some difficult decisions about which spending items should be cut to make way for its new spending programs.

Blowing past their own deadlines

By Trevor Tombe, professor of economics at the University of Calgary and a research fellow at The School of Public Policy

Budget 2024 continued a long tradition for the current federal government: increasing spending above and beyond its own previous plans. We have seen this ratcheting-up in each and every budget, year after year, both before the COVID-19 pandemic and now long after.

This year alone, the budget plans to spend about $25 billion more than what budget 2023 projected for 2024 and over $58 billion more than what budget 2022 projected.

Plans appear to mean very little. And this matters. Had its financial plans in budget 2022 been maintained, instead of a nearly $40 billion deficit this year, the surplus would be roughly $18 billion. Had it stuck to plans from 2023, the budget would be balanced by 2027, rather than the nearly $27 billion deficits that budget 2024 now projects.

To be absolutely clear, though, the federal debt trajectory hasn’t changed much. Indeed, it looks slightly better in 2024 than it did in 2023. Tax increases, the advantages and disadvantages of which I’ll discuss in a later article, and a stronger-than-expected economy are helping to offset higher spending this year.

But regardless of whether one agrees or disagrees with any particular spending decision, the ability to focus on and deliver on what the government itself commits to is clearly in short supply. That should be concerning for more than just the fiscal consequences. It may mean that the quality of public services is undermined as the government shifts its focus to rolling out one new program after the next.

And, perhaps most unfortunately, it risks undermining public confidence in the government’s own projections. After all, they’re almost guaranteed to be tossed within a matter of months.

Houses require land to be sold

By Chris Spoke, a real estate investor and the founder of August, a Toronto-based agency that designs and builds digital products

We all already know by now that housing in Canada is very expensive and that it’s very expensive because there’s not enough of it. According to Scotiabank Economics, we have less housing per capita in Canada than in any other G7 country.

We clearly need to build more housing.

To build housing, you need land. You then need to get that land approved by the municipality in which it sits for development.

There’s a lot that can be–and has been–written about the unwillingness of municipal politicians to approve enough land for development. Pierre Poilievre calls these people “municipal gatekeepers.” Doug Ford calls them his “municipal partners.”

But let’s stick to the land itself.

To develop land, a developer needs to buy land from a willing seller at a price that works for development. There are a few things that we could do with policy to increase the pool of willing sellers. One such thing would be a capital gains tax deferral on these transactions so long as any proceeds are reinvested in real estate. Both Conservative leaders Andrew Scheer and Erin O’Toole had a capital gains deferral on real estate interactions in their platforms when they ran against Justin Trudeau in the 2019 and 2021 federal elections.

A similar mechanism exists in the United States. It’s called the 1031 Exchange and it helps increase the liquidity of land markets. This was a good idea that’s long overdue.

With this 2024 federal budget, the Liberal government is going in the exact opposite direction.

Instead of making it easier for landowners to decide they’d like to sell their land to developers for development, they’re going to increase the inclusion rate–the portion of capital gains on which tax is paid–from 50 percent to 66 percent. This of course makes it more expensive for landowners to sell their land.

We can expect this to have a material negative effect on land transactions and a concomitant reduction in new housing development.

Given that housing in Canada is very expensive and that it’s very expensive because there’s not enough of it, this policy change will help make a bad situation much worse.

Glimmers of housing hope

By Cara Stern, host of the Missing Middle housing podcast with economist Mike Moffatt

Finally, after years of worsening housing affordability, the Liberals have put forward a budget that puts housing front and centre.

Much of the boldest housing news had already been released in the lead-up to budget day. I love the plan to incentivize provinces and municipalities to change zoning rules that have hindered new supply (a key recommendation of the Blueprint for More and Better Housing). That plan also came with requirements that were surprisingly conservative, such as a freeze on development charges for three years. They also made some much-needed changes such as a commitment to exempt apartment construction from EIFEL rules, rules that would have made it more difficult and expensive for multinational developers to build in Canada.

One surprising announcement is the increase to capital gains taxes. I suspect it’ll play well among those priced out of real estate. Its effect on the housing market, though, is likely to be mixed.

It could deter some investors from competing with first-time homebuyers as it makes buying investment properties a less attractive investment, though investors are useful for getting new homes built and adding rentals. It may also deter current housing investors from selling their investment properties. I’m surprised the government didn’t delay the capital gains tax increase very long, giving people a chance to sell their investment properties at current rates, which would quickly add homes into the ownership market. Anyone who wants to do so only has until June 25.

Canadians were likely shocked to learn that federal governments hadn’t previously planned their temporary immigrant levels, but this government is changing that. A decrease of up to 600,000 temporary immigrants is huge, and seeing the Liberals highlight that number several times shows just how much conversations on immigration have changed in that even politicians feel comfortable saying the doors to the country are too wide open.

One more highlight: a common response to people arguing for more housing supply is that developers won’t build if it means prices come down, preferring instead to sit on vacant land until there’s housing scarcity. This budget came with an announcement that the government would begin to consider taxing vacant lands. “Consider” is not the most promising language, but it’s an interesting step that could spur quicker development if done right.

Some of these bold housing announcements are ones that frankly should have been done years ago, but they have the potential to be transformative if the provinces and municipalities step up. I hope it challenges the opposition parties to go even bigger in their platforms.

Start-ups beware

By Nicholas Neary, a bond market investor and trader with DV Group

Canadian bond prices are little changed following the release of yesterday’s federal budget. In other words, the record $228 billion pace of bond issuance in fiscal 2024/25 had already been anticipated. This is about a 9 percent increase from fiscal 2023/24, and it’s more than twice the pre-pandemic pace. Canada arguably has very little fiscal room to buffer a recession or exogenous shock.

It seems like the government will continue its purchases of 50 percent of the Canada Mortgage Bonds (CMB) issuance, which is credit easing via fiscal policy. The government plans to amend the Borrowing Authority Act to remove all purchased (including future purchases) CMBs from the net government debt. In theory, this could allow the government to purchase the remaining CMBs (the 50 percent they aren’t currently purchasing) without further raising the borrowing limit.

There is a broad consensus that Canada’s productivity issues are partly driven by a lack of private capital investment. It seems odd, therefore, to further discourage this by raising capital gains tax rates. Canada just became a far less friendly jurisdiction for start-ups.

Unfortunately for Canada, higher borrowing costs are here to stay

Rudyard Griffiths, The Hub’s publisher and co-founder.

Last September after Prime Minister Trudeau cockily predicted that “…interest rates are going to start coming down probably middle of next year…” I wrote a rebuttal in The Hub that concluded “All of us—homeowners, businesses, and governments—should be tuning out wishful thinking that low rates are just around the corner and start preparing for higher bond yields for the long term.” I take some satisfaction in reporting that today the yield for the global benchmark for government debt or the U.S. ten-year bond is once again trading over 450 basis points and could soon be back on its way to 5 percent.

This matters for the federal budget that was just unveiled. Bond traders have come to renewed appreciation this winter and spring that the central bank mantra of “higher for longer” short-term interest rates increasingly applies to the entire yield curve. Growing geopolitical instability (think Ukraine and the Middle East); the continuing decoupling of Chinese and American economies, and the resulting re-shoring of supply chains; large-scale public investments in green energy and climate change mitigation; and persistent, sky-high government deficits all point to higher bond yields and debt servicing costs.

This isn’t speculation. It is the reflection of how billions of dollars of debt are being traded every day and priced by investors who are asking for more yield to compensate them for a higher neutral rate (e.g. the short-term interest rate that neither impedes nor encourages growth) and a growing term premium or the additional yield required to compensate for the unknowns associated with holding longer-term debt. The former impacts the short-term rates, set by central banks. The latter is shaped by inflation expectations, the issuers’ creditworthiness, and overall debt levels. Predictably our political class is the last to appreciate the implications of the reversion that is underway from the previous decade of easy money to a world of structurally higher borrowing costs.

As such, the forecast for interest costs, deficits, and the total size of the public debts presented yesterday need to be taken with a large grain of salt. It is not simply that all will likely be revised higher twelve months from now. It is that Canada has started the climb onto a permanently higher plateau of borrowing costs. As the second most indebted country in the world as measured on by the total debt of governments, households, and non-financial corporations as a percentage of GDP (we are behind Japan and ahead of Greece) this matters.

It will matter for future public expenditures as debt servicing costs eat away at the government’s fiscal capacity. It will negatively impact productivity as the re-financing of large public debts at persistently higher rates raises corporations’ financing costs. And, it will burden individual Canadians with higher mortgage rates and personal credit as the “risk-free” return of benchmark government yields remain elevated at a “new normal” for years to come.

None of these issues were addressed by Tuesday’s budget. Instead, they were compounded and made worse by the continuation of irresponsible levels of deficit spending and a prime minister who is clearly clueless about the big structural shifts going on in the global economy. Shifts that reinforce, with each passing day, the cost of capital for everyone and everything, is headed in one direction: up and to the right.

Three cheers for the Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program

Karen Restoule, vice president at Crestview Strategy and co-founder of BOLD Realities

While Budget 2024 offers up several contentious propositions, the Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program isn’t one of them. Industry and First Nations leaders across the country welcomed this much-needed program with roaring applause citing it as the vehicle to transform Canada’s resource sector by increasing First Nations ownership in resource projects and getting projects built more quickly.

The program was first announced, without details, as part of the 2023 Fall Economic

Statement, and was in large part the result of years of advocacy from the First Nations Major Projects Coalition. Since then, several First Nations groups publicly voiced concerns that the Trudeau government—as it has been known to do—would narrow qualifying criteria to reflect its ideological bias towards what it has considered to be “clean energy” projects, thereby excluding key Canadian sectors like oil and gas and traditional mining.

The Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program announced on Tuesday will include up to $5 billion in loan guarantees to facilitate access to capital for First Nations. And, to everyone’s surprise, it will be “sector-agnostic”, leaving it up to First Nations to develop the resources that we have in our own backyards.

This announcement isn’t just about large numbers and government promises. It’s a game-changer for First Nations who have been entangled by the Indian Act for more than 150 years, prevented from leveraging assets for financing or pursuing large-scale economic development projects on our own terms. By providing financial backing for banks to loan funds to First Nations for projects, it lowers the risk and potentially increases the willingness of financial institutions to fund these ventures.

We have seen a successful application of the loan guarantee program in Ontario since

its launch in 2009, where there have been 11 loan guarantees totalling roughly $500

million supporting ownership in projects across the province. However, success has

been limited given that the program is offered to renewable energy infrastructure and

transmission projects only.

It was former Premier Jason Kenney’s introduction of the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation (AIOC) in 2019 that was the first to support First Nations self-determination, helping facilitate access to capital for First Nations to any sector. In just five short years, it has provided more than $680 million in loan guarantees to 42 groups. The AIOC has been lauded as the model for the country.

There is no question—this program applied at the national level not only has the potential to increase the scale, scope, and speed of economic development in Canada. It will lead to greater economic independence and self-reliance for First Nations across the country. Fingers crossed that Canada’s limited state capacity doesn’t get in the way.

The wild ride of federal finances

By Livio Di Matteo, a professor of economics at Lakehead University.

“Come, come on a ride

I’ll take you through the stars, space, and time

Words won’t mean a thing

‘Cause there’ll be no words where we’re going…”

– “Green Man” by Jake Bugg (listen here!)

Budget 2024 is a remarkable document in that it continues an upward ride in federal spending that is divorced from the country’s long-term economic productivity fundamentals. When one looks at the GDP growth projected in the budget, assuming population continues to grow at two percent annually, real per capita GDP from 2023 to 2028 will decline. Indeed, the period from 2018 to 2028 will essentially be a lost decade of per capita income growth. Yet, the 2024 budget sees rising revenues and expenditures through to 2028, despite the economy’s productivity stall.

In many respects, the budgetary projections in the 2024 budget do not mean much as they will likely change yet again within a few short months. For example, between the federal 2023 spring budget and the 2023 fall economic statement, the expenditure forecast for 2024-25 grew by six billion dollars. For the year after, it grew by $15.4 billion dollars. Indeed, by 2027-28, spending in the fall 2023 economic statement was $18.2 billion dollars higher than what was projected for that year only a few months earlier.

The 2024 budget takes all those projections to a new and higher level of meaningless words, given the plethora of spending announcements unleashed in the weeks preceding the budget and re-released in the document itself. Relative to 2022/23, budget 2023 projected spending by 2027/28 to be 15.7 percent higher, but in the fall 2023 economic update, it was going to be 19 percent more. It is now projected to be 21.3 percent higher.

So, in the span of barely 12 months, projected spending for 2027/28 went from $555.7 billion to $574.8 billion, and is now expected to reach $586.3 billion—a $30.6 billion dollar difference. And yet, the forecast for the federal deficit is that it will decline from $40 billion in 2023/24 to $23.8 billion in 2027/28, even while debt service costs over the same period will rise from $47.2 billion to $60.9 billion.

How can this be? Because, along with an expansion of spending designed to buoy support for a flailing government, there is also an optimistic forecast of revenue growth which budget 2024 forecasts at just over 25 percent from 2022/23 to 2027/28, as a result of higher taxes and a growing economy.

Of course, missing here are the dynamic effects of an increase in capital gains and corporate taxes on economic activity. After all, higher tax rates alone will not be enough to raise revenues, if new wealth is not created. While expenditure forecasts are likely to be revised upwards, expect to see the revenue projections scaled back as the year unfolds. After all, how can Canada expect to see federal revenues rise faster than expenditures in an environment of declining productivity and rising taxes? There really are no words to describe the ride we have embarked on.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

RCMP spending to protect MPs may have risen 112% since 2018, as Canadian politicians face greater rise in threats

Trevor Tombe: Canadians are paying billions in hidden taxes on new homes