Despite heightened political rhetoric and ambitious housing targets from both the federal and Ontario governments, housing starts are not going to be increasing any time soon. In fact, the CMHC is forecasting that they are far more likely to fall over the next couple of years. Ontario’s situation appears particularly dire.

We should recognize both federal and provincial housing targets for what they are: an expression of need, rather than what is likely to occur. Ontario has set a target for 125,000 housing starts this year, 150,000 in 2025, and 175,000 every year thereafter. Yet the provincial government’s own budget forecasts only 88,000 starts this year (roughly 70 percent of the target), and less than 95,000 in both 2025 and 2026 (not quite 55 percent of the target). And given current conditions, if I were a betting man, I’d be taking the under in terms of the government even meeting its own inadequate projections.

There are solutions, though: our Blueprint for More and Better Housing has dozens of them. At a high level, the province needs to fix broken regulatory processes, enact a strategy to lower land costs, and reduce the high taxes and charges that are crushing new development.

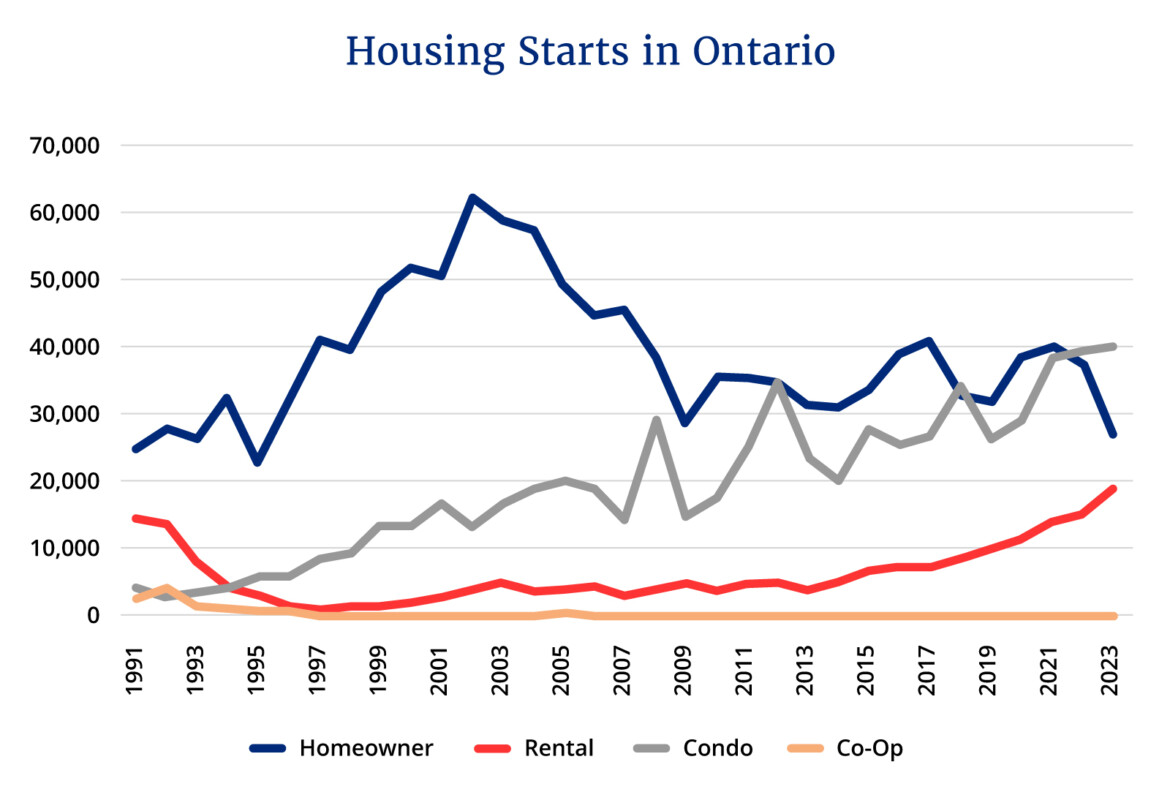

Housing starts can be broken down into three distinct markets: rental apartments (also known as purpose-built rentals), condominiums, and non-condo ownership housing. In recent years, condo and rental starts have been rising, while ownership starts have been in freefall. While Ontario’s rental apartment market might trudge on, the outlook for both forms of ownership housing looks exceptionally bleak.

Let’s start with non-condo ownership housing. Starts in this market are down 35 percent over the past two years and are less than half what they were twenty years ago. High land costs, along with development charges that have risen by as much as 2000 percent over the past 20 years, make these expensive to build, even before a shovel is in the ground. When they do get built, they’re typically at the edge of cities, or in smaller communities, and as such tend not to attract mom-and-pop investors who would prefer properties that are easier to rent out (either on a long-term or short-term basis), such as those closer to downtown or near a college or university. At current prices and interest rates, only the most well-off owner-occupiers can afford to purchase these homes. That will not change unless there is a significant drop in interest rates or a significant drop in land prices or taxes on development. Expect starts in this market to continue to fall.

Unlike non-condo ownership housing, condo starts are currently at record highs in Ontario, which is normally indicative of a strong market. However, the starts represent strong pre-construction sales during the pandemic and before the rise in global interest rates. Since the interest rate spike, pre-construction condo sales in the Greater Toronto Area have dropped to levels not seen since the 2008-09 financial crisis and are at levels more associated with the 1990s.

This crash in sales will inevitably be reflected in new starts, mostly likely in the next six to 18 months. Potential first-time homebuyers cannot qualify for mortgages at today’s prices and rates, and high taxes and land costs create a price floor on how low condo prices can fall. Unlike newly constructed non-condo ownership housing, the pre-construction condo market does attract high numbers of mom-and-pop investors. With high interest rates and weak potential price appreciation, it simply is not an attractive investment, as shown by a recent blog post by Steve Saretsky. Condos will not get built without a buyer, and there are few to be found.

Unlike the other two markets, it is possible to make a bullish case for Ontario’s purpose-built rental market. All of the people who are shut out of the ownership market need to live somewhere, creating a need for rental. A suite of new housing policies, from eliminating the GST on purpose-built rental construction to the reintroduction of the 10 percent accelerated capital cost allowance to enhanced access to low-cost financing, has positively altered project economics by lowering both taxes and interest costs. These factors should help Ontario’s rental starts continue to grow.

However, it is also possible to make a bearish case for rental starts as well. Development charges continue to rise in Ontario, and the eventual passage of Bill 185 will remove the requirement for municipalities to phase in those increases. Financing can still be difficult and expensive to obtain, and municipal approval processes still slow development. Canada has the second slowest speed in the OECD to obtain construction permits (just ahead of the Slovak Republic), and cities in Ontario lag behind their counterparts in other provinces when it comes to approval times.

Some developers that I have spoken to believe that Canada’s plan to reduce international student enrollment may have the intended effect of reducing rental housing demand, making new supply a less attractive investment. But the biggest factor may be global interest rates. Why engage in a risky activity like apartment construction when you can simply buy a risk-free 10-year U.S. Treasury that yields nearly 5 percent a year?

We’ve seen a lot of great action this year from the federal government, but if we want to see developers build even during this challenging economic environment, we need the province to step up and make it easier to do so.

Recommended for You

Derrick Hunter: Canada can no longer afford to indulge in net-zero nonsense

Peter Tertzakian: Want to get pipelines built? Let Canadians own a piece of the action

Travis Toews: Canada needs a leader who takes economic growth seriously—and that requires being all in on energy investment

Brad Tennant: The poutine-petrol alliance—why Alberta and Quebec should team up in their fight against federal overreach