DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

The burning issue right now in Canada is the cost of living—and it’s not going away anytime soon. Despite the inflation rate slowing to 2.9 percent in March, Canadians remain anxious, and recent polls show that sentiment is only worsening.

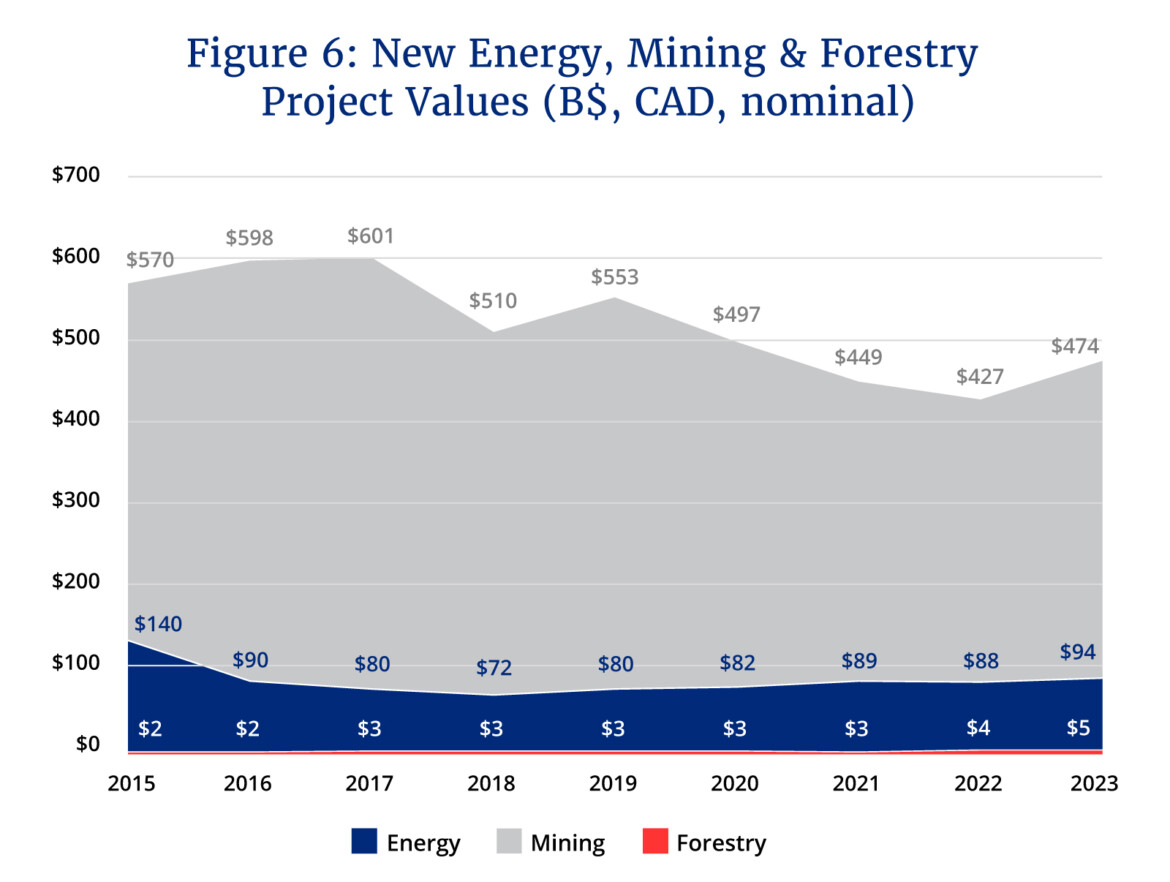

A big reason for Canadians’ discontent is that while inflation (year-over-year price growth) may have slowed, price levels are still far higher than in mid-2021 when they first began to take off. Between March 2021 and March 2024, food prices, for instance, have risen overall by a crushing 21 percent. Shelter is similarly up by 20 percent. There’s no sign that either will retreat to lower levels anytime soon (see Table 1).This DeepDive was written prior to last week’s release of Statistics Canada’s April CPI data. As such, the data in this table are reflective of March 2024.

If policymakers want to address price levels themselves, it prompts the question: what can they do about them?

The problem, like so many in economics, is that there is never one cause. Any pro-affordability agenda needs to address the different factors that have contributed to higher prices and rising costs for Canadians.

There are five forces that have driven inflation in Canada and around the world:

- Supply chain constraints and geopolitics

- Monetary policy

- Fiscal policy;

- Firm behaviour and competition

- Housing

This DeepDive aims to outline various causes of Canadian price inflation and offer some substantive ideas as to what governments can do to make the lives of Canadians more affordable.

1. Supply chain constraints and geopolitics kickstarted it all

When we think about causes of inflation, the usual suspects have been around for many years— corporate greed, ultra-low interest rates, and too much federal spending—but notwithstanding the presence of these different factors, inflation remained low for more than a decade. Research from the U.S. Federal Reserve shows that what really kicked off the recent spike in inflation was the unprecedented supply chain disruptions from COVID-19. Factory closures, transportation delays, and labour shortages all reduced supply for many products and drove up production costs as a result. At the same time, the Russian invasion of Ukraine drove energy, fertilizer, and global commodity prices upwards causing a 1.2 percent increase in Canada’s inflation.

The greatest inflationary effects accumulated while much of the economy was shuttered or suppressed for months and people stayed home due to COVID restrictions. People delayed purchases and demand built up over time so that when everything did reopen, a flood of pent-up demand flooded our depleted supply of goods and services and led to shortages that drove up prices. Research from the Cleveland FED shows that much of the increase in inflation in the U.S. and Eurozone was caused by supply problems that made it impossible for producers to meet resurgent demand.

Supply chains are now back to normal and COVID disruptions are gone, but geopolitical disruptions remain, continuing to impact trade. This is not limited to the Russia-Ukraine war but also growing disruption in the Middle East, fresh rounds of U.S. tariffs on China, the potential for Donald Trump to further upend the trade order, etc. We must consider how to protect our economy from such shocks in the future. It is important to be realistic—we cannot divorce ourselves from global supply chains, but we can improve our resilience to shocks, both domestic and international.

Policy Solutions

- Reinforce Canada’s energy independence by ensuring that we have sufficient energy and natural resource infrastructure to serve our entire country from our own resources, to cope with supply shocks, and to support our allies.

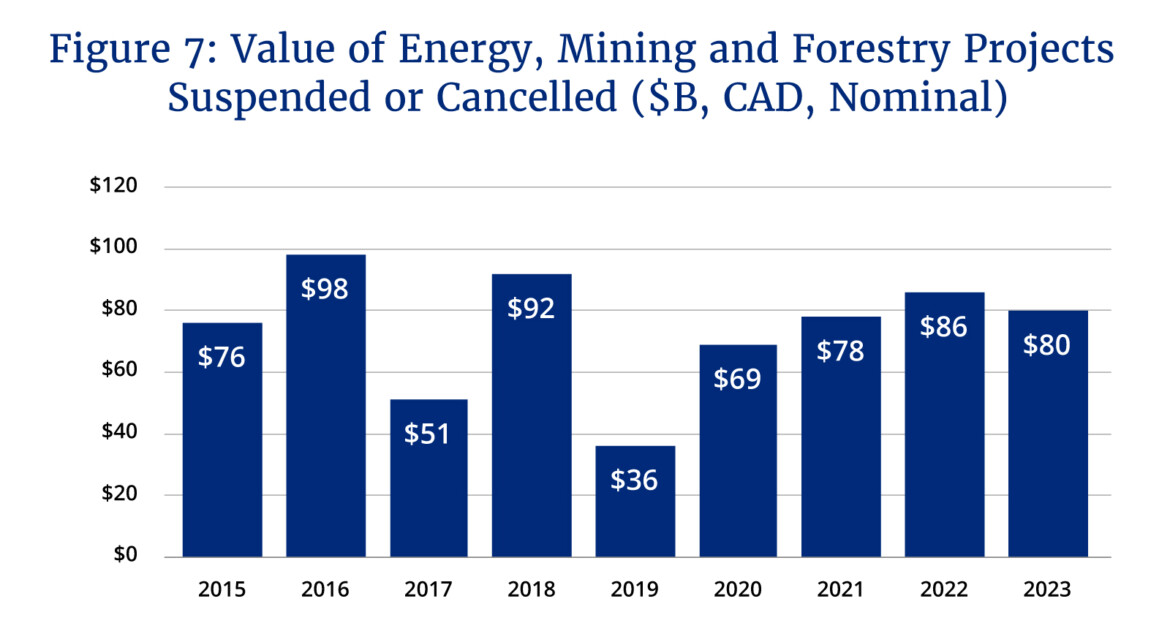

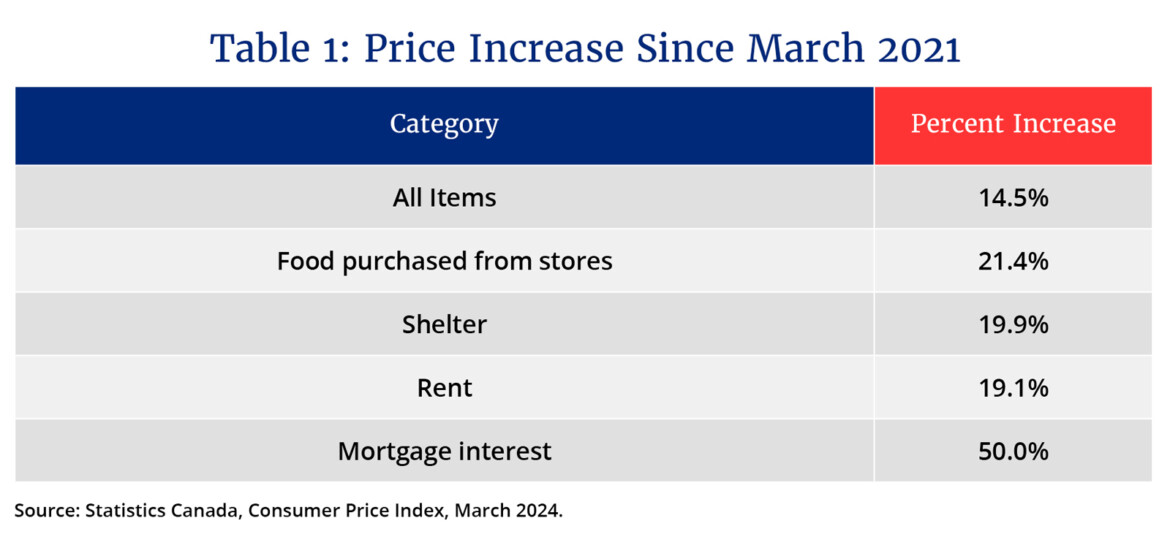

- We also need to dramatically accelerate the approvals process for Canadian production of rare earth minerals. As Minister Wilkinson has noted, “It cannot take us 12 to 15 years to open a new mine in this country.” Canada’s extremely burdensome environmental review processes are undermining the viability of its energy independence by causing a collapse in investment—the number of major natural resource projects completed between 2015 and 2023 declined by 36.4 percent. We never want to be in a situation like Germany, which has seen permanent structural demand destruction due to its dependence on Russian natural gas.

- Canada should make massive investments in our trade infrastructure, including ports, rail, and airports so that in the event of a future shock, the country easily has the capacity to surge imports to make up for a shortage or to double exports of fertilizer or LNG to support our allies. This would have the welcome bonus of boosting Canadian productivity by helping exporters get their goods to market more quickly and cheaply. In addition, it can be productivity-enhancing. Economist Trevor Tombe has pointed out that we need more funding for critical infrastructure because “our transport infrastructure is inadequate and our productivity suffers as a result.”

- Create incentives for “friend-shoring.” Simplify the customs paperwork and regulatory requirements for importing products from allied countries (those with which we have trade agreements) and make it tougher to import from other countries with increased scrutiny around human rights and forced labour, and tariffs for countries with a track record of dumping, trade abuses, and IP theft.

2. Monetary policy failed to apply the brakes

The fact that inflation hit 8.1 percent in June 2022 while interest rates were rising faster than at any point in Canadian history has demonstrated that the Bank of Canada, like many central banks throughout the advanced economies, held interest rates too low for too long and continued quantitative easing when it was no longer needed.

When inflation did appear, central banks initially declared it “transitory,” a temporary phenomenon that would take care of itself. They then found themselves behind the curve, offering too little too late and in need of unprecedented interest rate hikes, from 0.25 percent to 5 percent in a little over a year.

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve has come under considerable criticism for policy mistakes. As Larry Summers put it:

I do think there needs to be considerable soul searching at the Fed as to how they missed this as badly as they did. They were declaring that inflation would be transitory through most of 2021, even as it was becoming clearer and clearer to a growing number of observers that inflation was not a path to being purely transitory.

To his credit, the Bank of Canada governor did some of the soul-searching recommended by Summers. Tiff Macklem wrote in February 2024 that he and his team had underestimated the strength and persistence of inflation in 2021 and 2022 in the midst of a series of shocks. Also, the Bank’s models weren’t properly calibrated to measure price pressures throughout the economy, he wrote, and Bank officials were “not sufficiently attentive to the risk that inflation could rise sharply.”

To be fair, it would also have been impossible for the Bank of Canada to foresee how serious the COVID crisis would be. A shutdown of the Canadian economy could have lasted years and been far more devastating. As then-governor Stephen Poloz explained, “A firefighter has never been criticized for using too much water.”

It’s not at all clear that the performance of the Bank of Canada has been worse than other central banks. It is entirely possible to argue that the Bank did well in engineering a “soft landing.” Nevertheless, the inflation crisis precipitated by the pandemic has proven the need to reinforce the Bank’s inflation mandate and improve Parliamentary oversight without harming the Bank’s independence.

Policy Solutions

- Clarify the bank’s mandate. The government of Canada must clarify that the Bank’s mandate is price stability: the 2 percent inflation target and nothing else. Not inclusive growth or climate change or digital currency. When the Bank of Canada renewed its mandate in 2021, a number of economists raised the alarm about odd language “promoting maximum sustainable employment” in the joint statement from the Bank and the government. As McGill University economist Chris Ragan has stated, “All of us should be worried about the future. If the government is not really committed to having an operationally independent Bank of Canada pursuing low and stable inflation, then there is good reason to expect that inflation and inflation expectations may become unanchored.”

- Conduct an independent review of quantitative easing and unorthodox monetary policy by a team of respected economists. The Bank of Canada has already talked about some of the mistakes that it’s made, but its judgment isn’t being subjected to independent analysis. There needs to be an independent audit to ensure real accountability.

- Improve Parliamentary oversight, particularly for unconventional policies. If the Bank of Canada wishes to implement unconventional monetary policies such as quantitative easing, the governor should be required to make an appearance at the House Finance Committee to explain the rationale, risks, and benefits, and provide a written report to Parliament. Of course, the Bank of Canada’s independence would remain unaffected, but the accountability would ensure democratic oversight.

3. Fiscal policy fuelled the inflation

In response to the COVID crisis, governments around the world spent massive sums to counteract the effects of shutdowns across the economy. We’re now seeing a consensus emerge that inflation was driven by the excessive size of COVID stimulus packages which injected massive amounts of stimulus into the economy at a time of supply constraints. Research also shows that the governments that spent the most had the highest inflation, while the more moderate spenders have had lower inflation rates to contend with.

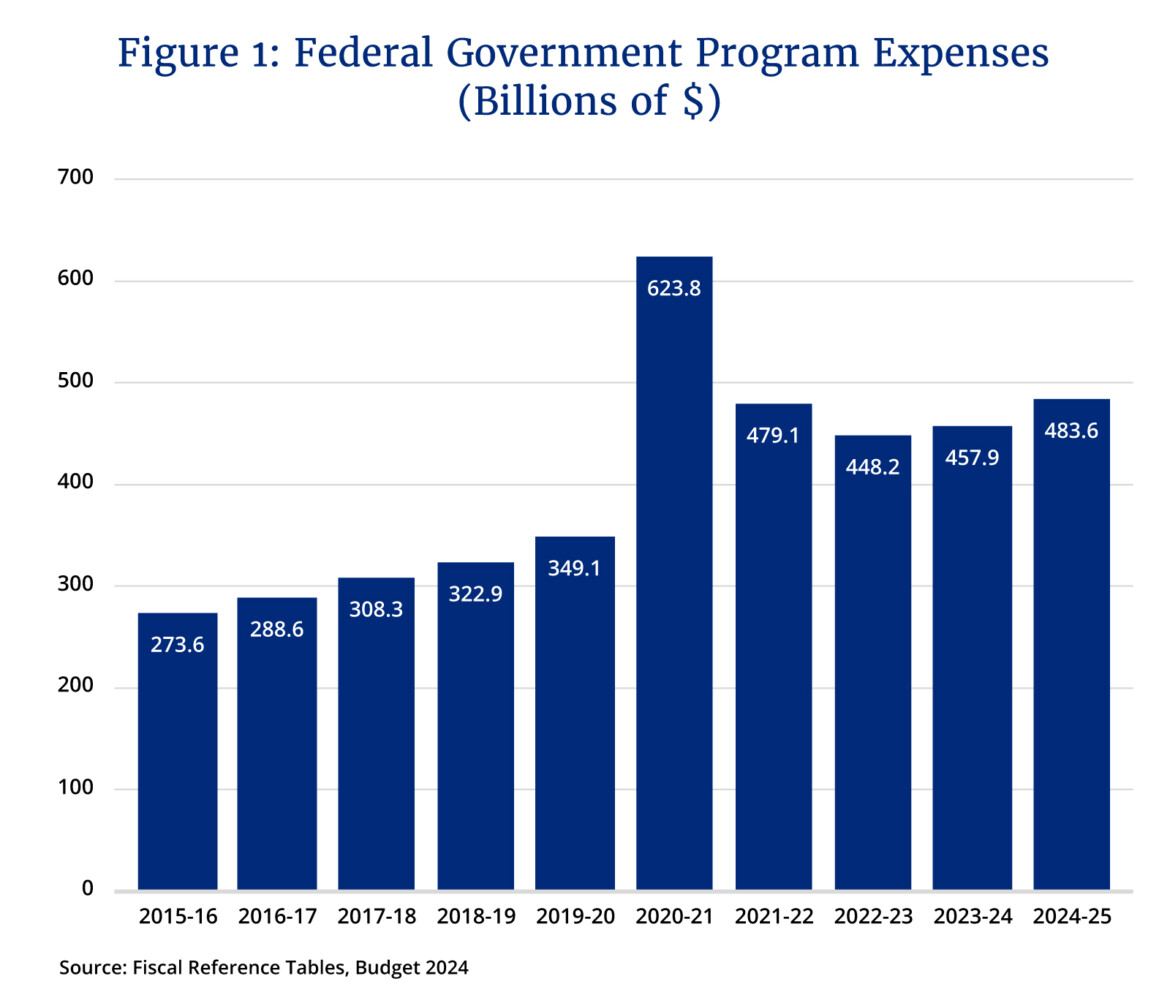

In Canada in 2020-21 (see Figure 1), federal program expenditures almost doubled from $349 billion to $623 billion, an increase amounting to 14 percent of GDP. And the spending kept on coming: an additional $130 billion or 6 percent of GDP in 2021-22 and another $100 billion or 4.5 percent of GDP in 2022-23. This pushed an explosion of demand (almost 20 percent of GDP) into our economy of diminished supply and created shortages that drove prices sky-high.

On top of this, provincial program spending surged by 9.2 percent in 2020-21 to $504.4 billion and an estimated further 5.6 percent to $532.9 billion in 2021-22. This is a much smaller percentage increase than the near doubling of federal spending. However, most provincial spending never retreated when the COVID crisis passed. Ontario, B.C., and Quebec all have program spending this year which is above the peak COVID budgets in 2021 and 2022.

The fact that the government of Canada was unable to turn off the spending taps, even when it became clear that the COVID crisis was over and inflation was accelerating, made it more difficult for the Bank of Canada to cool the economy. Effectively, the Bank was hitting the brakes while the federal government and many provincial governments were flooring the accelerator. According to Scotiabank, excessive government spending forced the Bank to raise interest rates by an additional 2 percent.

Overall federal program spending remains well above pre-crisis levels at 16 percent of GDP compared to the 13.2 percent average before the crisis. Despite all this, Budget 2024 just added another $5 billion of annual spending annually and it’s no doubt to head even higher as we get closer to an election in 2025.

Policy solutions

- The federal government should cease or postpone all new spending programs until inflation stabilizes within target and the Bank has lowered the policy rate to neutral levels. This will prevent excess spending from pushing interest rates higher. If fiscal and monetary policy are not working in tandem, they will be working against one another.

- Establish a credible path back to a balanced budget. Even if it takes say five or more years, it is important for investors and markets to understand that the government is serious about fiscal discipline in order to bring down long-term interest rates. Shifting fiscal guardrails or anchors is not enough.

- Adopt an internal budgeting system where new spending priorities can only be funded by reallocating from existing programs that are less needed or underperforming. This will force departments to prioritize and reinforce with the public that there is no need for cuts. The Trudeau government has taken tentative steps toward spending reviews, but these have not produced any significant savings so more rigorous processes are needed.

4. Firm behaviour and competition

Some left-wing politicians in Canada who believe that inflation is caused by corporate greed alone have been summoning grocery store CEOs to various Parliamentary committees to yell at them. Instead, they should listen to economist Brian Albrecht who says: “Blaming inflation on greed is like blaming plane crashes on gravity.”

It may be literally true that planes crash because of gravity, but gravity is a pre-existing condition that has always been with us. Planes ought to fly in spite of gravity. Similarly, corporations have always sought to maximize profit, but they can provide low prices in spite of their desire to make money by ensuring competition.

Nevertheless, we can’t be too dismissive about firm behaviour and competition. Isabella Weber has written some fascinating work on sellers’ inflation, defined as “when the corporate sector manages to pass on a major cost shock to consumers by increasing prices to protect or enhance its profit margins.” In a normal competitive market economy, firms are extremely reluctant to hike prices across the board, even when they’re under pressure from rising costs because they fear losing out to competitors.

But imagine there is a supply chain crisis that affects all retailers and they know for certain that all of their competitors will have to raise prices. Then they’d be a fool not to raise prices concurrently with their competitors.

In fact, IMF research showed that in Europe rising corporate profits account for almost half of the increase in inflation in 2021 and 2022.

The Bank of Canada has done some great research comparing inflation rates and corporate profit margins. It found that:

While changes in markups may have contributed to the initial rise of inflation in 2021, their contribution dissipated by the end of 2021 and growth in marginal costs was the driving force of peak inflation. […] during 2021 the contribution of markup growth to inflation was positive but mild—inflation during 2021 was 5.1 percent, whereas markup growth was only 0.44 percent over the same period (less than one-tenth the rate of inflation).

The evidence for sellers’ inflation is somewhat mixed and the concept may be more theoretical than practical. Still, the only way to ensure that profits are not excessive is to foster a real competitive policy environment to bring down prices. One critical point is that competition law by itself cannot create competition. Competition laws in Canada have been strengthened with increased penalties at least three times without having much of a noticeable effect on prices.

There are two ways to lower prices by encouraging competition. The first is to eliminate many government barriers to competition, including: a) restrictions against foreign businesses; b) state-owned monopolies; and c) regulatory barriers to entry. Research by George Mason University Economist Vincent Geloso estimated that 32.6 percent of Canada’s economy is effectively protected from competition.

The second is to provide incentives to encourage investment in concentrated sectors (e.g. airlines) or in regions (rural areas where there are one or few grocery stores), or overall, by making Canada a more attractive place to invest with tax incentives or bringing down the high cost of doing business in Canada through regulatory reforms and tax reductions.

The ultimate goal is to push down prices by having multiple companies investing and competing aggressively to steal customers from one another. This cannot be achieved by having the industry minister cold-calling foreign grocery stores to ask them to come to Canada. Particularly in the current environment, who would respond to Canada’s invitation to invest hundreds of millions in order to be constantly threatened with excess profit taxes on top of high costs, onerous regulations, and carbon taxes?

It’s time to make Canada an exciting place to invest and build a business.

Policy solutions

- Reduce or eliminate government barriers to competition in the form of foreign ownership restrictions, state-owned monopolies, and regulatory barriers that impact almost a third of Canada’s economy.

- Bring in a ten-year corporate tax holiday for new capital investments in areas that require more competition. If a grocer (Canadian or foreign) builds a new store in an underserved area, they get 10 years free of corporate income tax.

- Ban mergers and acquisitions for businesses in the sectors that are already too concentrated (telcos, banks, grocery stores), so that they are prohibited unless the minister makes an exception. This would reverse the onus so that a proposed merger would by default be disallowed unless it can be demonstrated that it would not damage competition.

- Slash regulation. Begin a government-wide overhaul to reduce regulation by appointing a minister responsible for red tape reduction, and set a 30 percent reduction target for every federal department. The government should also establish a “regulatory budget” working with business to calculate the costs that are imposed by regulation and then setting a declining overall “budget” for the costs of regulation that might be imposed in a given year. This approach led to significantly improved economic performance in British Columbia according to research from George Mason University.

- Allow full expensing of all capital investments in the year they were made. Canada currently allows some accelerated write-downs already, but these are being phased out, which will cause a huge tax increase on business investment taxes, according to Trevor Tombe. Canada needs to reduce the competitiveness gap and provide more investment incentives.

5. Housing—The toughest nut to crack

Right now, the fastest-growing parts of inflation are in housing, the sector that is driving the greatest unhappiness among young people. In March, rents grew by 8.5 percent compared to a year ago while mortgage interest costs were up 25 percent, and owned accommodation costs rose 7 percent.

In the short term, the problem is not going to get better—in fact, the housing shortage will get worse this year and will be even worse next year—because Canada’s construction industry cannot keep pace with the growth in population.

The government’s latest target to build 3.9 million homes by 2031 would require eight years of building almost 500,000 homes per year. There is simply no one in the housing industry who thinks that this is remotely achievable. Canada’s housing starts are currently at about 240,000 per year and are projected to trend lower this year before a modest recovery according to the CMHC.

Canada certainly does not have the workers to double the rate of home construction, but we also don’t have the capital, with an estimated $1 trillion required to build the additional homes.

Proportionally, Canada is building homes much faster than the Americans. The U.S. is currently building 1.5 million homes annually, which is the equivalent of Canada building just 150,000. If the government’s strategy to accelerate construction were able to build 280,000 or 290,000 per year, it would be a heroic achievement, roughly twice U.S. levels.

Why our construction industry can’t catch up and why U.S. homes are so much cheaper

The U.S. brings in 1 million permanent residents per year and its temporary worker visa programs are proportionally smaller than Canada’s (in the U.S., 900,000 of the various H Visas were approved last year alongside 472,000 international students). Canada’s official target is 500,000 permanent residents. But when one accounts for international students, temporary foreign workers, and other non-permanent residents, Canada brought in 1.3 million immigrants in 2023, which is five times U.S. immigration levels.

The CMHC projection that we’ll have a shortage of 3.5 million homes by 2030 is based on Canada having a population of 43 million by 2030. In fact, Canada’s population is already at 40.8 million and will hit 43 million in just over two years. (The reduction in international students will slow Canada’s population growth from 1.2 million per year to 900,000-1 million per year.) This means that Canada is on track to face CMHC’s 3.5 million housing gap sometime as early as 2026 rather than 2030.

The government and the official opposition have proposed a series of thoughtful and effective policies to accelerate home construction, but there are limits to how much supply can be increased. The point is that even if you build 250,000 or 300,000 homes per year while the population is growing by 1 million per year, then the housing shortage will continue to worsen as demand will far outstrip supply.

Policy solutions

- Canada’s annual immigration target of permanent residents (i.e. 500,000 annually) needs to be overhauled so that the provinces that are responsible for so many of the policy levers related to immigration settlement (including education, health care, housing, etc.) are involved. The federal government should set a much lower target in order to accommodate the global talent streams, family reunification, and asylum seekers. On top of that, each province would be able to accept additional immigration up to the number of homes built in the previous year. They could determine how to allocate among the various categories (skilled, temporary foreign workers, etc.) based on the needs of their industries.

- Every college or university should have sufficient rental accommodation available to accommodate substantially all of its international students. The federal government could provide cheap loans to support educational institutions in building residence facilities.

Key takeaways

In conclusion, addressing inflation in Canada requires a decisive approach that covers all the five forces behind the rise in prices over the past few years. By enhancing energy independence, bolstering trade infrastructure, and refining monetary and fiscal policies, Canada can pave the way toward a more stable economic future. Additionally, fostering greater market competition and adjusting immigration targets to align with housing capabilities are essential steps.

As we implement these solutions, we can do even better: improving productivity, capital investment and innovation will drive up the wages of Canadian workers with better jobs. Thus, a future DeepDive will cover how to raise Canadian wages. The ultimate goal is to not only stabilize prices but also support sustainable growth and improve the quality of life for all Canadians.

Recommended for You

Christopher Dummitt: Four ways Pierre Poilievre and the Conservatives can fight woke ideology

Kaisha Bruetsch: The economic case for clean electricity is now undeniable—just ask Ontario

The Week in Polling: Young British Columbians want to escape their costly province, Trudeau’s successor, mandatory national service in the U.K., and the Edmonton Oilers

The Weekly Wrap: Poilievre proves he’s no empty populist with capital gains pushback