We have now reached a moment of truth for at least two major central banks. With the Federal Reserve all but certain to keep rates steady at the June federal open market committee meeting, and most likely into late July as well, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Canada (BoC) must now decide whether to essentially go it alone at rate decisions tomorrow.

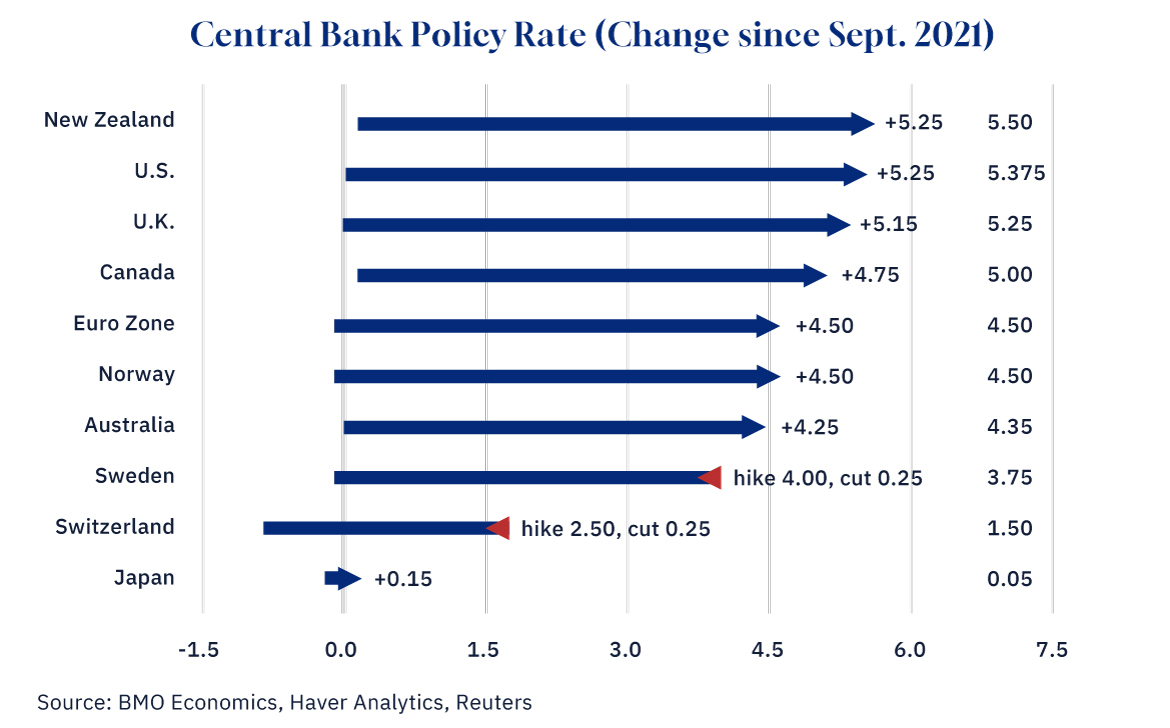

There actually doesn’t seem to be all that much debate at the ECB. Even with a mild upside disappointment in the early read on Euro area May inflation— both headline and core Consumer Price Index (CPI) came in a tick high at 2.6 percent and 2.9 percent, respectively— officials have heavily signalled a rate cut is coming on Thursday. Following the earlier lead of first Switzerland, then Sweden, the ECB is widely expected to clip its refinance rate 25 basis points to 4.25 percent, nearly two years after first lifting it from zero.

The picture for the Bank of Canada is much less clear-cut. With its much tighter linkages to the U.S. economy, it’s a much bigger decision for Canada to carve out a quasi-independent policy path. But, unlike the U.S. experience so far in 2024, Canada has seen a run of better-than-expected inflation results, cutting all major measures of core inflation to below a 3 percent annual pace, and below a 2 percent trend in the past three months.

And the final piece of the Bank of Canada’s puzzle—Q1 real GDP—came in much lighter than expected at 1.7 percent growth, on the heels of a big downward revision to the prior quarter to just 0.1 percent (from 1.0 percent). Even with a rebound in April, the bigger picture is that GDP is up less than one percent in the past year, compared with almost 3 percent year-over-year U.S. growth over the same period.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

In other words, the U.S. economy has outpaced Canada’s by more than 2 percent in the past year, a very wide gap indeed. The U.S. core consumer price index is running at 3.6 percent year-over-year, almost a full point above the comparable measure in Canada. And, the U.S., unemployment rate has nudged up a half point in the past year to a still-low 3.9 percent, while Canada’s jobless rate has jumped a full point to 6.1 percent. Reinforcing that message, the job vacancy rate in Canada has fallen all the way back to pre-pandemic levels at 3.4 percent. Pulling all these threads together, there is a very good case for the Fed to remain patient, but there is an equally good case for the Bank of Canada to begin trimming rates, forthwith.

Recommended for You

‘The race is tightening up’: Darrell Bricker on what the polls are showing heading into the final weekend of the election campaign

Derrick Hunter: Canada can no longer afford to indulge in net-zero nonsense

Peter Tertzakian: Want to get pipelines built? Let Canadians own a piece of the action

Travis Toews: Canada needs a leader who takes economic growth seriously—and that requires being all in on energy investment