In each EconMinute, Business Council of Alberta economist Alicia Planincic seeks to better understand the economic issues that matter to Canadians: from business competitiveness to housing affordability to living standards and our country’s lack of productivity growth. She strives to answer burning questions, tackle misconceptions, and uncover what’s really going on in the Canadian economy.

In March, the Bank of Canada declared that Canada’s productivity problem is an emergency. And that improving it “needs to be a priority for everyone.”

Productivity is the amount of goods and services produced for a given amount of “input,” often measured by GDP per hour worked. Importantly, a more productive economy is the only thing that leads to sustained wage growth without feeding inflation.

Canada’s productivity is not only low but has failed to show strong progress for decades.

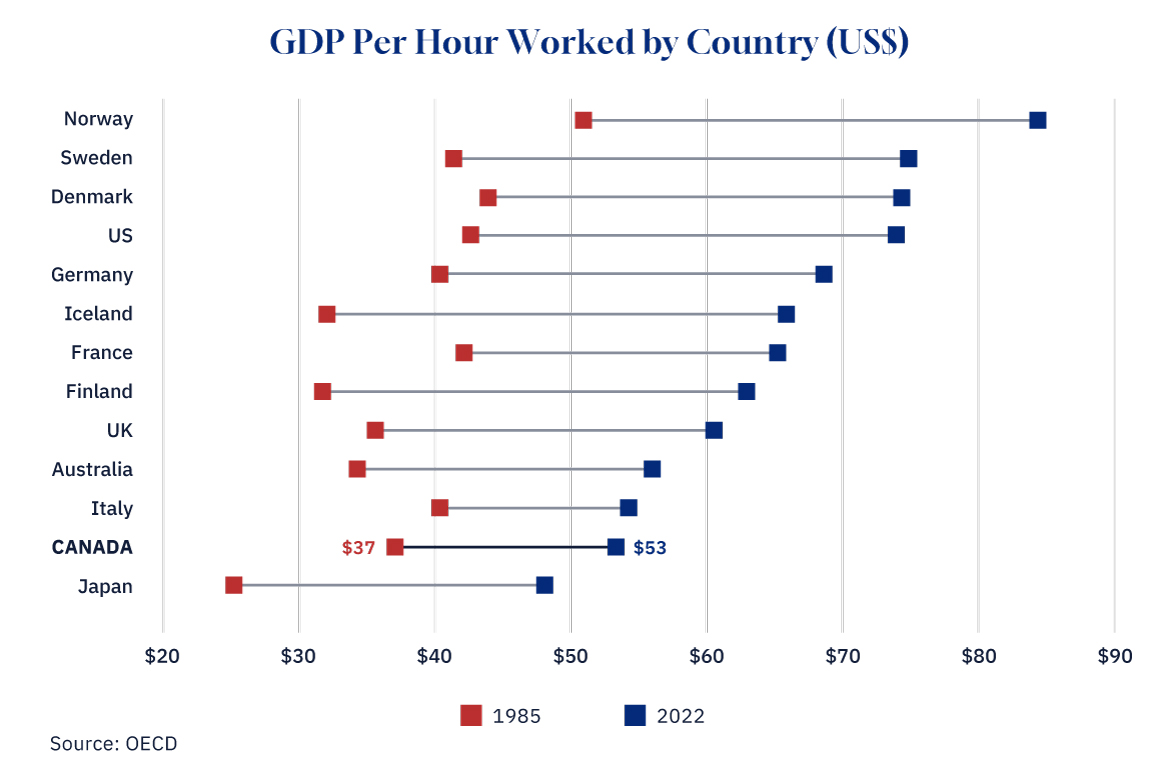

As of 1985, Canadian workers produced $37 of value per hour worked compared to $43 in the U.S.—around 87 percent of U.S. levels. By 2022, productivity had reached $53 per hour worked in Canada but $74 in the U.S., leaving us at just 72 percent of U.S. levels (all figures in USD).

It’s not just that we’re falling behind the U.S., either. Relative to a dozen other comparably rich countries, Canada saw the least growth of any assessed, except Italy. Countries like Germany, France, and Sweden that used to be on relatively equal footing with Canada have all left us in the dust. Meanwhile, many countries that used to trail Canada (like Australia, the U.K., Finland, and Iceland) now boast a productivity advantage. Overall, Canada’s ranking has fallen from 8th to 12th.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Canada’s low and sluggish productivity isn’t a matter of Canadians not working hard enough. Productivity is high when workers have what they need—the tools, skills, and technologies—to do good work most efficiently. Think of a lumberjack cutting down trees; having a chainsaw allows them to cut far more, and more quickly, than with an axe. Canada’s poor performance suggests our economy is running on old tools and technologies with limited investment—all of which, it turns out, are true.

There is no shortage of explanations for why that is. But improving Canada’s productivity may not require that we settle on its precise cause(s) to get to reasonable solutions. To reverse the trend that is otherwise set to continue, Canada will need to figure out how to best incentivize investment in the kinds of things required—e.g., research, technology, and innovation—to enhance productivity; and more critically assess the kinds of policies that will stymie it.

This post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.