While Newfoundland and B.C. couldn’t be farther apart geographically, their premiers recently came together to declare the current equalization formula unfair. This is an exciting development that breathes life into the important task of rebalancing the federation to make governments more accountable and our economy more prosperous in the long term.

With Alberta and Saskatchewan calling for similar reforms since Alberta’s equalization referendum in 2021, there is finally momentum for overdue repairs to this flawed, bloated, and divisive program.

The two newcomers to the stage have different bases for their critiques, but their perspectives are valid and point to some of the bigger problems with the outdated formula. B.C.’s concerns in particular give insight into the bigger picture in Canada as the federal government grows unsustainably and elbows its way into more provincial areas.

Newfoundland has launched a court case, arguing that the recently renewed equalization formula fails to meet its constitutional objective of ensuring provinces can provide “reasonably comparable levels of services at reasonably comparable levels of taxation.” It has two main arguments: first, that the full inclusion of resource revenues penalizes provinces for developing their resources; and second, that the formula makes no effort to measure the relative costs between provinces of delivering “reasonably comparable” services.

The first complaint is not new (how to measure resource revenue is always controversial in these discussions), but the points made in Newfoundland’s initial letter to Ottawa are clear and compelling: the development, regulation, and management of natural resources have significant costs for provincial governments. When the equalization formula fully counts revenues but ignores costs it punishes those who develop their resources and rewards those who do not.

Alberta’s government released a position paper a year ago where a hypothetical government that receives equalization is considering opening up a new sector to develop its resources. This new productivity will generate revenues for the province, but that will be somewhat offset (and thus discouraged) by a clawback of equalization entitlement.

What is worse, however, is that the costs to the government of standing up a regulatory regime for the sector combined with the loss in equalization (which ignores those costs) could perversely make provincial coffers poorer.

Canada is facing a productivity crisis, but equalization rewards governments who choose not to pursue growth. This inherent flaw needs to be minimized, beginning with the treatment of resources.

The second point Newfoundland raises is that the formula has copious variables to calculate a province’s fiscal capacity—that is, its ability to raise revenue—but entirely ignores what “reasonably comparable services” would cost in each province.

At Fairness Alberta we have made this argument repeatedly, but Newfoundland’s case takes it in a slightly different direction by focusing on its geography. It points out that it has three times the land mass of its neighbouring Maritime provinces, but only one-quarter the population. This lack of population density clearly makes service delivery more expensive but as they note, the Maritimes have received $45 billion over the last 10 years through equalization while Newfoundland has received nothing.

Our focus regarding measuring needs has been on the different costs of living in different provinces. This translates to different construction costs, and most importantly different salary needs to get a “relatively comparable” level of social services staff. Even if we can pin down a fair estimate of what New Brunswick or Quebec needs to reach the median wealth of provinces, if it only costs them 85 percent as much to build a hospital and staff it as it does in B.C. or Ontario then it is unfair to make taxpayers in B.C. and Ontario pay to get those provinces all the way to the median while their own hospitals go understaffed.

One solution to this problem is to factor CPI into the needs side of the equation. Hub contributor Trevor Tombe helpfully added this variable to the equalization simulator at Finances of the Nation and it makes a significant difference, including making payments less necessary overall.

Another solution proposed in the Alberta government’s position paper cited above is to gradually phase down the ambitions of the program such that it brings all provinces only to 95 percent of the median rather than 100 percent. Given the many gaps in the formula, in seeking to make the less productive provinces “relatively equal” we should err on the side of redistributing a little less rather than taking too much—especially when all provincial governments are struggling on the front lines to keep up with inflation and population demands.

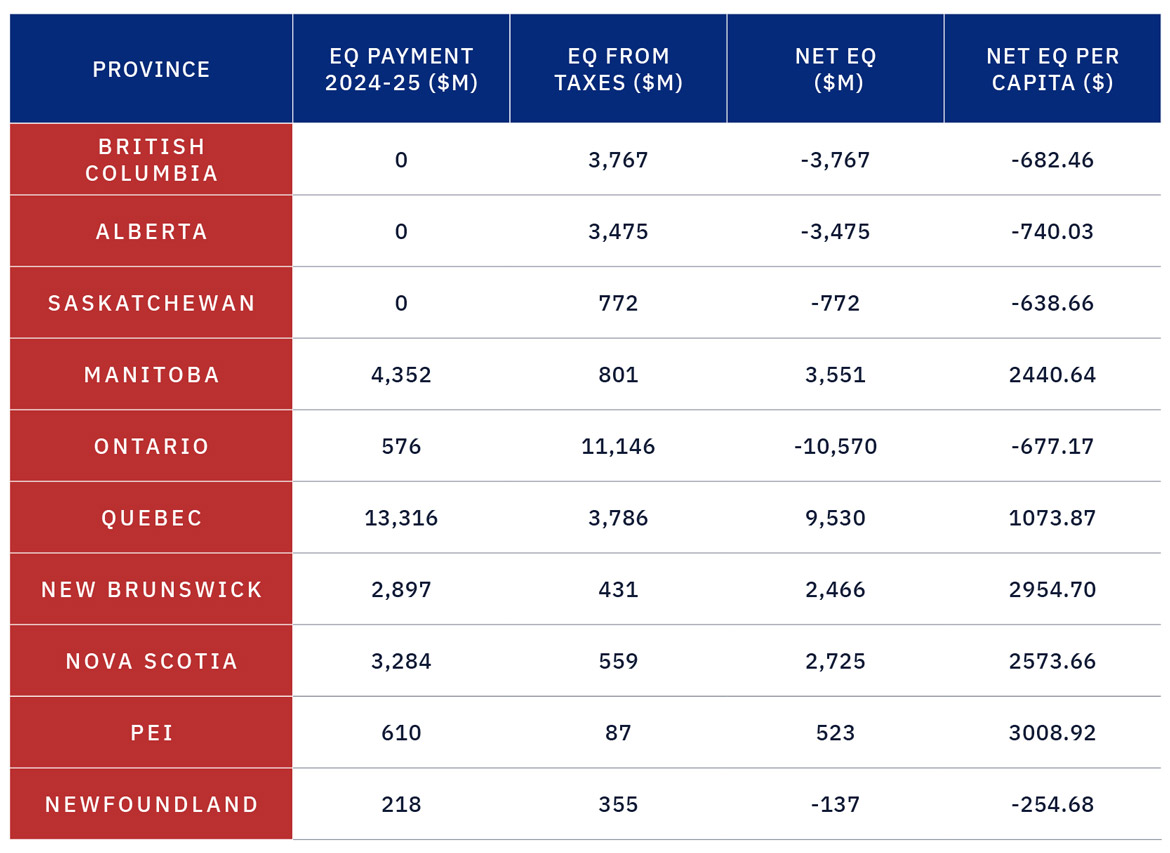

The other reason to worry about the equalization program over-redistributing brings us to the main concern raised by B.C.’s premier: Ottawa is generally taking too much in taxes from places like B.C. and then spending too many of those dollars elsewhere. This refrain is usually sung by Albertans but it makes sense for B.C. to chime in given that in 2022 British Columbians sent $2,895 more per capita to Ottawa than was returned in federal spending (second only to Albertans’ $4,272).

In total dollars, that is a record of over $15 billion in federal taxes from B.C. that Ottawa spent elsewhere. In Alberta’s case it was closer to $20 billion, which is the annual average that Albertans send on a net basis.

B.C.’s premier noted that decisions on infrastructure spending, economic development, and of course equalization are all avenues by which Ottawa taxes wealth from the West and spends it to the East. Equalization accounts for about $3.7 billion of the $15 billion net from British Columbians so he is right to note there is a bigger picture of hidden equalization behind the flawed flagship program.

While his remarks about infrastructure and economic development skewing to the centre (especially the tens of billions of dollars for battery plants not yet on the books) are on point, where the B.C. argument missed the mark is in attacking Ontario’s equalization payments. As a “have” province it is odd to see Ontarians get around $500m this year and next, but Ontarians collectively are paying about $11 billion of the $25 billion equalization tab.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The reason for this small top-up for Ontarians highlights the most important flaw in the program: its budget rises with GDP every year, and even when provincial economies get more equalized (and regardless of the federal deficit) it all has to be spent. After being brought up to 100 percent of the median, the rest of the budget goes to over-equalize the have-nots. The reason for that small Ontario top-up is because the program is lavishly bringing their fiscal capacities higher than Ontario’s.

Ontarians are the largest group of Canadians who are harmed by this bloated and flawed program. Through equalization, they are collectively sending $10.5 billion in taxes ($677 per capita) to their neighbouring provincial governments to cover social services while their own government struggles with austerity measures to get its budget in order.

Opening up equalization gives us a chance to reform fiscal federalism to improve accountability and productivity while calming simmering regional tensions

The momentum is building, and solutions are in sight: it is time for Ontario to join with the other four “have” provinces to make a supermajority coalition that no federal government—or party hoping to form government—can ignore when it comes to equalization reform.