The following is the first installment in a multi-part series tackling Canada’s housing and immigration crises. The series will focus on their root causes, intertwined nature, and potential solutions.

That Canada’s current housing crisis is primarily a function of an incredibly misguided set of immigration policies should have been blindingly obvious quite some time ago.

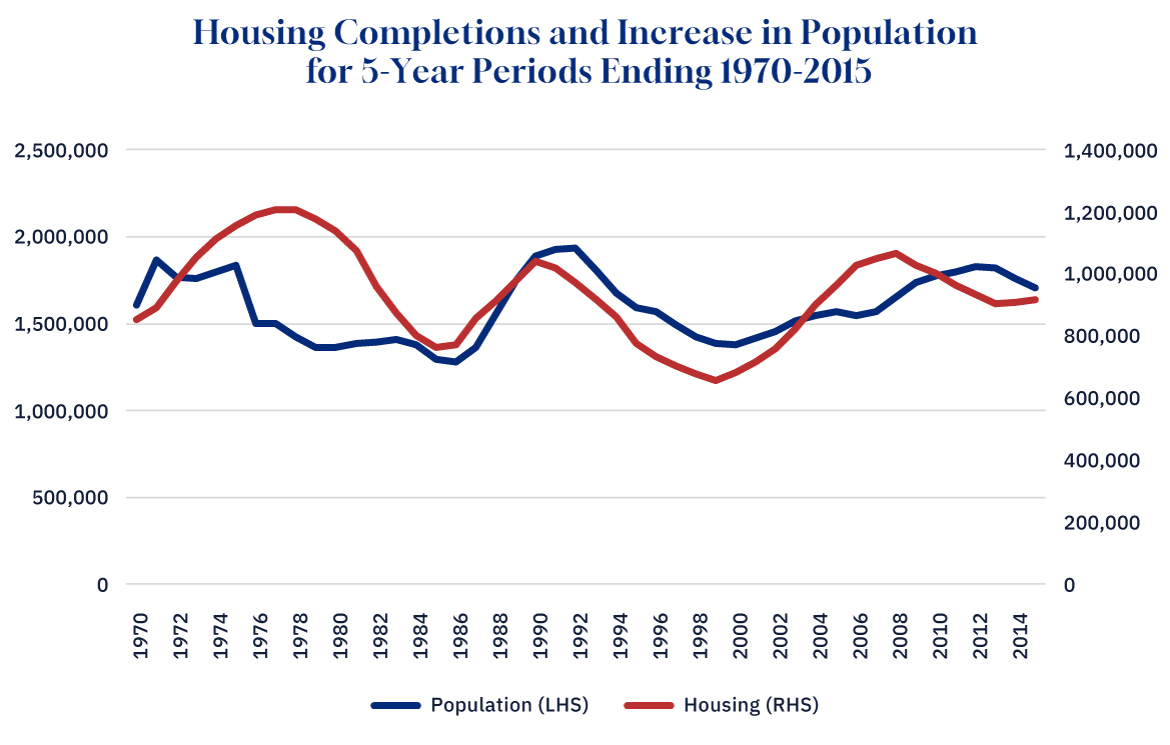

The figure below compares the five-year increase in Canada’s population to the five-year total of housing completions from 1970 through 2015. (The figures for 1970 represent the 5-year totals for 1966-70, and so on.)

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Note how there was essentially no trend in either series over this period. The average annual increase in population starts out at 322,000 in 1966-70, gets as low as 255,00 in 1982-86, as high as 386,000 in 1988-92, and ends up at 341,000 in 2011-15. The average annual housing completions starts at 171,000 in 1966-70, gets as low as 153,000 in 1981-85, as high as 242,000 in 1973-75, and ends up at 183,000 in 2011-15.

Note also how, allowing for the ebbs and flows of the housing cycle, there is a rough correspondence between the growth in the population and the number of housing completions to accommodate that growth.

Now, look at what happens when we extend this series out to 2023.