In the lead-up to the November 2024 U.S. presidential election, The Hub and Pollara are teaming up to provide insights into what Canadians make of the race as it unfolds. Pollara senior advisor Andre Turcotte will provide exclusive polling and analysis to Hub readers, helping them understand how fellow Canadians are making sense of the election and its implications for Canada.

In late July 2024, before his selection as the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz stirred controversy when he labeled Donald Trump and Ohio Senator JD Vance as “weird” during an appearance on MSNBC’s Morning Joe. Speaking specifically about Trump, Walz remarked, “Listen to the guy…he’s just saying whatever crazy thing pops into his mind,” underscoring Trump’s unpredictable and often erratic behaviour.

This rhetorical jab was a strategic effort to diminish Trump’s credibility as a serious leader by painting him as irrational and disconnected from reality. Walz’s comments were no isolated critique. After the Democratic National Convention, he ramped up his attacks during a rally with Kamala Harris, proclaiming, “These guys are creepy and, yes, just weird as hell.” This blunt statement quickly went viral, turning into a catchphrase that came to define much of the 2024 campaign.

By characterizing Trump and his allies as “weird,” Walz tapped into a broader public frustration, capitalizing on the sentiment that Trump’s behaviour was not just unconventional but disturbingly erratic. This framing resonated with the voters who were weary of the instability and unpredictability often associated with Trump’s leadership style.

Walz’s tactic was not just about policy differences—it targeted the essence of Trump’s character. In doing so, he made it difficult for Trump and his allies to respond without amplifying the label. Attempts to defend against the “weird” label often seemed to confirm it, making it a particularly effective political weapon. The narrative of “weird” versus “normal” became a symbolic divide, with Democrats, led by the Harris-Walz ticket, positioning themselves as the guardians of stability and reason, while casting Trump and his camp as chaotic and disconnected from conventional norms of leadership.

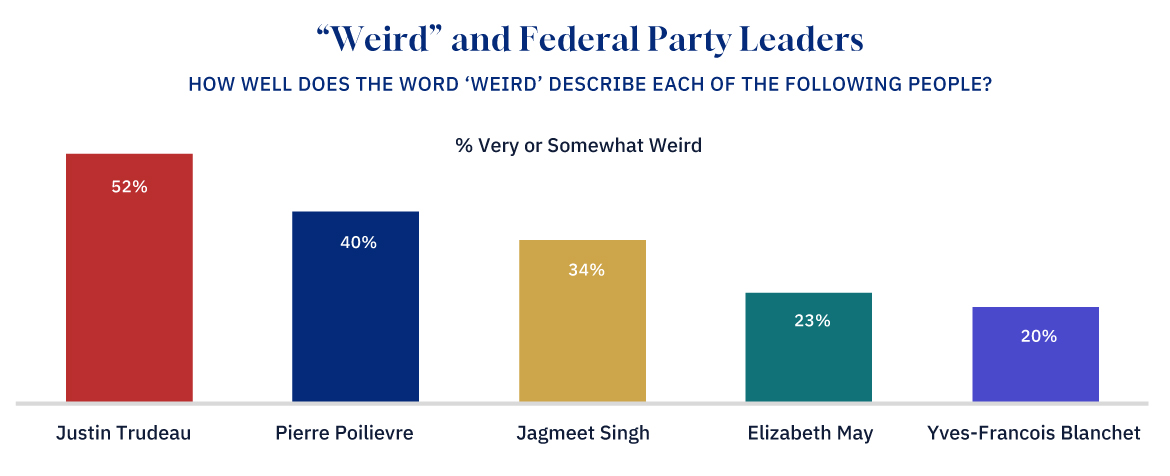

As is often the case, what happens in the U.S. eventually finds its way to Canada. I was interested to see if this rhetorical framing was not limited to U.S. politics. To explore this, Pollara Strategic Insights asked a simple question: “How well does the word ‘weird’ describe each of the following political leaders?” The results were revealing. A majority of Canadians (52 percent) agreed that the term “weird” aptly described Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

By comparison, 40 percent of respondents felt that Opposition leader Pierre Poilievre could be described as “weird,” while 34 percent felt the same about NDP leader Jagmeet Singh. Green Party leader Elizabeth May (23 percent) and Bloc Québécois leader Yves-François Blanchet (20 percent) scored lower, likely due to their lower profiles.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

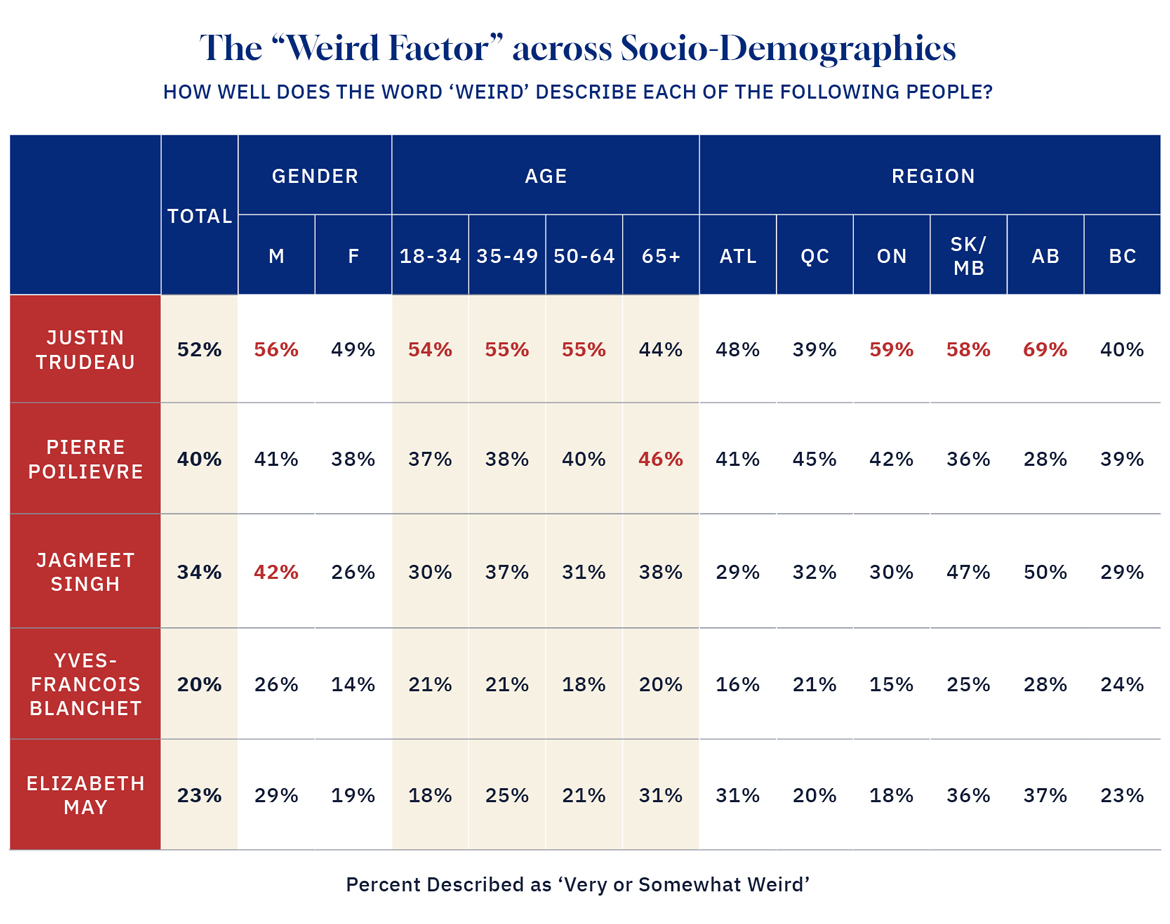

A closer look at regional data provided more insight into Trudeau’s situation. Albertans were the most likely to find Trudeau “weird,” with 69 percent of respondents in the province agreeing with the label. In Ontario and the Prairies, that number was slightly lower, at 59 percent and 58 percent respectively, while Atlantic Canada showed a 48 percent agreement. British Columbians (40 percent) and Quebecers (39 percent) were less likely to apply the term to Trudeau.

The study also uncovered notable demographic differences. More men (56 percent) than women (49 percent) considered Trudeau “weird,” and Canadians under the age of 64 were more likely to hold this view (55 percent) compared to older Canadians (44 percent).

Most concerning for Trudeau, however, was the revelation that 22 percent of Liberal voters found their own leader “weird.”

Poilievre, while ranking lower than Trudeau on the “weirdness” scale, still had reasons to be cautious. Older Canadians (46 percent) and Quebecers (45 percent) found him “weirder” than other federal party leaders, potentially signaling challenges in key voting blocs.

Singh, while lower overall in “weird” perceptions, still faced significant scrutiny, with 42 percent of men, 47 percent of Prairie voters, and 50 percent of British Columbians finding him “weird.”

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

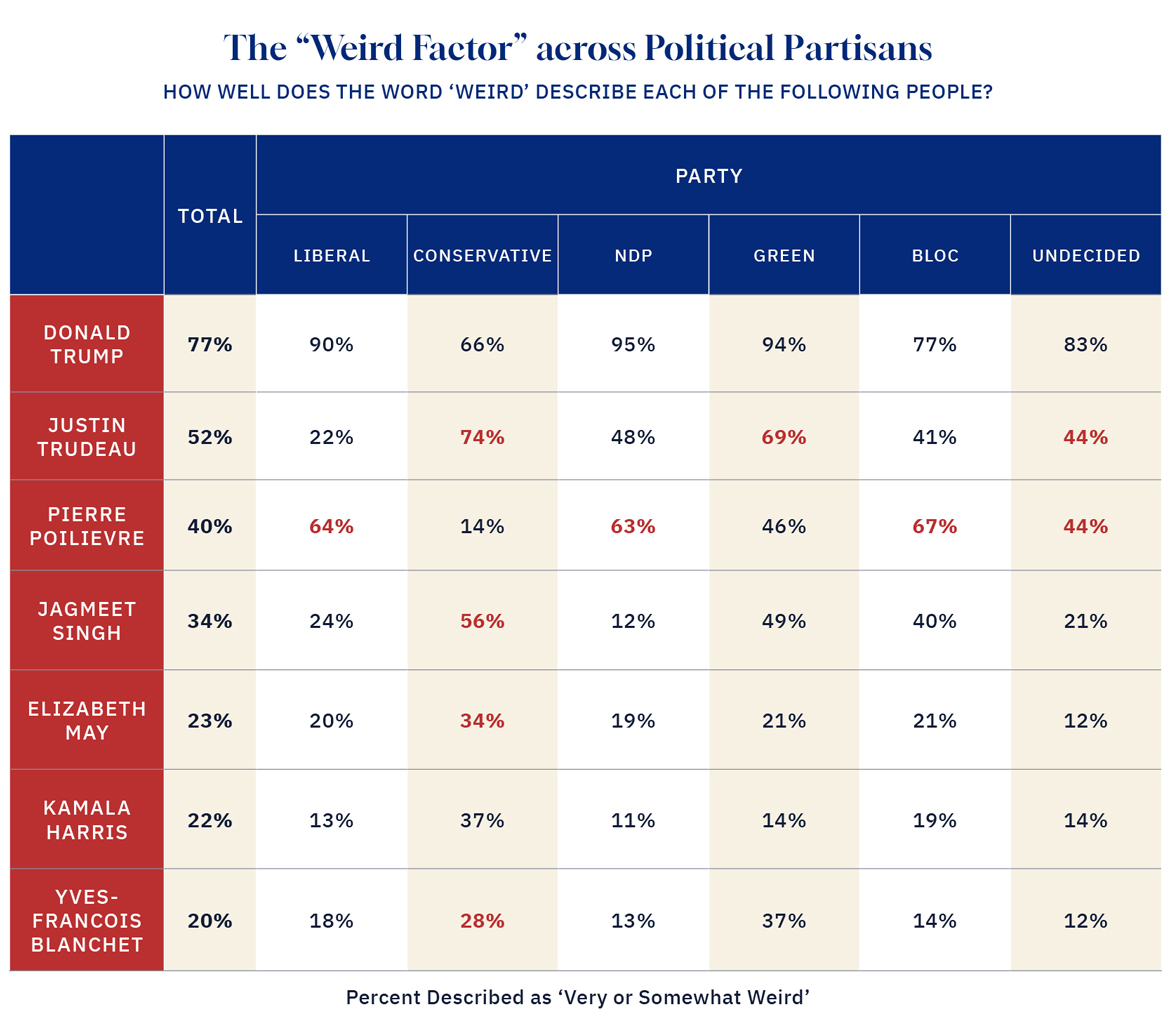

Despite these findings, Canadian political leaders can take some solace in the fact that no matter their individual “weird” scores, they pale in comparison to those of former U.S. president Trump. An overwhelming 77 percent of Canadians viewed Trump as “weird,” a consensus that transcended regional, gender, and partisan divides.

By contrast, only 22 percent of Canadians considered Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris to be “weird.” Trump’s divisive personality and erratic behaviour are having a unifying impact on Canadians across party lines. While 95 percent of NDP voters feel Trump is “weird,” this opinion is shared by 94 percent of Greens, 90 percent of Liberals, 77 percent of Bloquistes, and even 66 percent of Conservatives.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

As both the U.S. and Canadian elections are on the horizon, it remains to be seen how the “weird” factor will shape electoral outcomes. In the U.S., voters will soon decide whether this framing will harm Trump’s bid for re-election.

Meanwhile, in Canada, the “weird” label could become an increasingly salient tool for political challengers aiming to undermine opponents who seem out of step with the electorate. Whether being branded as “weird” ultimately proves to be a political liability or, in some cases, an unexpected asset, is a question that will soon be answered at the ballot box in both nations.

The findings in this op-ed are based on a sample of 1,500 adult Canadians conducted online. The survey was in the field between September 11th and 19th, 2024. While online surveys cannot be assigned a margin of error, the corresponding margin of error for a probability sample of this size is +/- 2.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. The margin of error will be larger when looking at sub-populations.