Welcome to Need to Know, The Hub’s roundup of experts and insiders providing insights into the economic stories and developments Canadians need to be keeping an eye on this week.

Carney’s borrowing ambitions are actually higher than Trudeau’s

By Sean Speer, The Hub’s editor-at-large

Mark Carney’s leadership campaign went to great lengths to create distance between him and the Trudeau government on economic and fiscal policy. His own policy backgrounder pointedly criticizes his predecessor’s overspending and expansion of government.

He’s said that he would separate the government’s operating and capital budgets and run a “small” capital deficit of roughly 1 percent of GDP—or what amounts to annual borrowing of about $30-35 billion per year.

This has been characterized in the media—and certainly implied by the Carney campaign—as less spendthrift than Justin Trudeau’s government.

What do the facts tell us? Is the Carney plan actually a tighter fiscal policy than the Trudeau government’s? The answer is not really.

Although the Trudeau government accumulated debt on an unprecedented scale, a significant share of its deficits and debt occurred during pandemic.

If you back out the two extraordinary pandemic years—2020-21 and 2021-22—the Trudeau government’s average annual deficit from 2015-16 to last year was just $27.3 billion. Its average deficit as a share of GDP over these years was barely 1 percent.

Carney’s fiscal plan may involve different definitions and a different composition of overall spending. But its borrowing ambitions in absolute terms and as a share of GDP are actually higher than has been the Trudeau government’s norm over the past decade.

These assumptions, it must be emphasized, are conservative. They take for granted that Carney fulfills his promise to balance the operating budget in three years. Yet, as I recently outlined, the federal deficit is nearly $50 billion and likely to rise in the face of economic uncertainty and the Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs. And that doesn’t even account for Carney’s promises of tax cuts and additional spending.

If he also runs an ongoing operating deficit, the cumulative deficit (operating and capital) could be far higher than what we’ve come to expect from the Trudeau government.

One can of course understand the incoming prime minister’s political interest in distinguishing his fiscal plan from his predecessor’s unpopular record. But the contrast between the two may prove to be unfavourable. Carney’s plans for borrowing and spending may ultimately be even looser than Trudeau’s.

The cost of Canada’s counter-tariffs

By Trevor Tombe, professor of economics at the University of Calgary and a research fellow at The School of Public Policy

Canada’s response to U.S. tariffs comes in many forms, with provinces pulling alcohol from shelves and suspending purchases from U.S. suppliers. But the most significant measure was a 25 percent tariff on an initial list of goods amounting to $30 billion in U.S. imports, primarily consumer goods and food.

While these tariffs target American exports, the reality is that Canadians will bear much of the cost. Given the size of our economy, we have limited ability to shift away from U.S. suppliers entirely. That said, some may argue that the cost is justified. Reasonable people will disagree on this point, but regardless of where one stands on the merits of retaliation, it’s important to track how these tariffs impact Canadians. That’s what I aim to do here. These are rough calculations, subject to some error, but they should provide a useful estimate.

With $30 billion in imports subject to tariffs—assuming businesses fully pass the tariffs onto consumers—the direct consumer impact is roughly equivalent to a half-percentage-point tax on overall purchases. On average, prices for goods imported from the U.S. could rise by 2.2 percent.

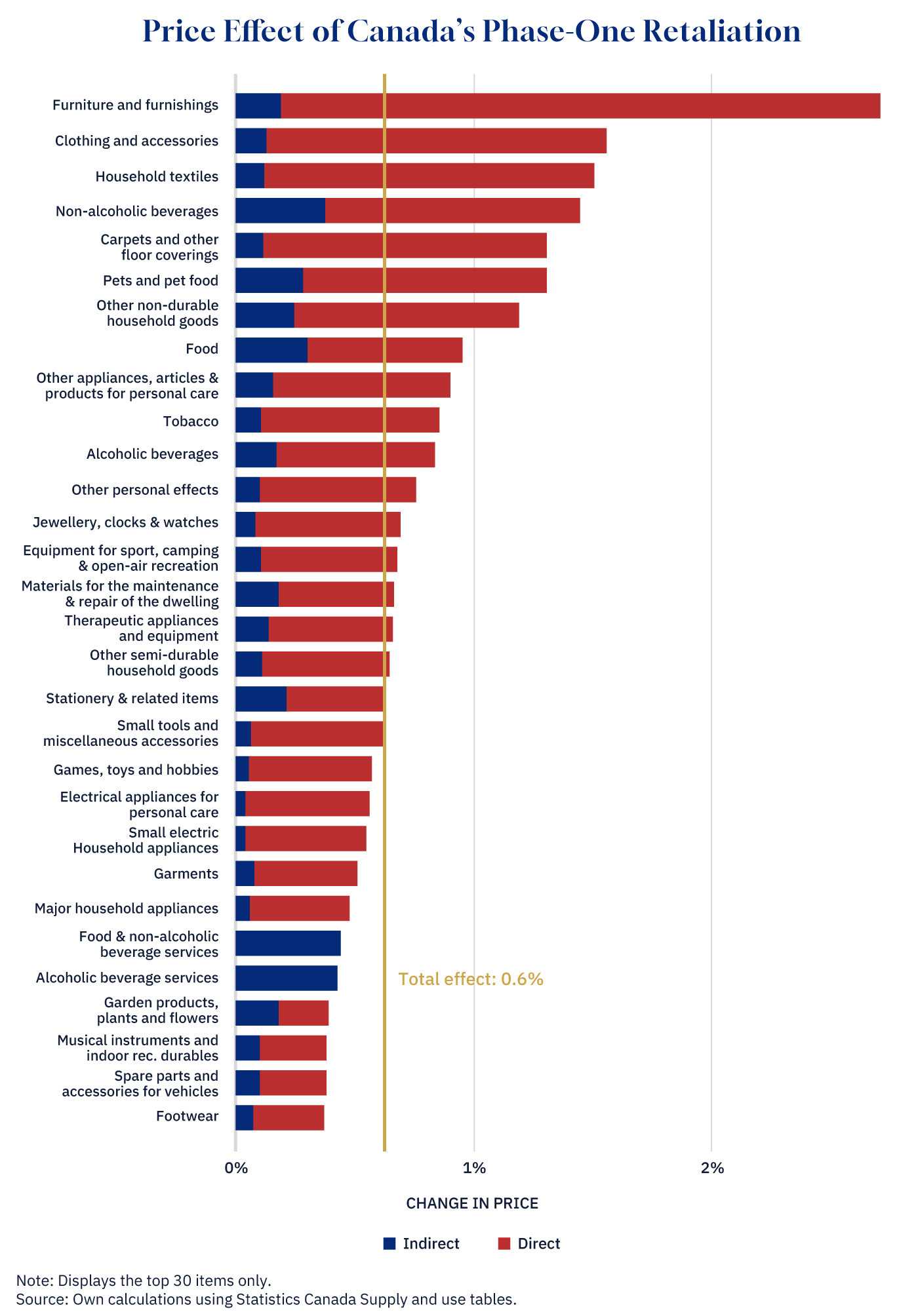

However, the impact extends beyond direct costs—tariffs ripple through supply chains, increasing costs across various industries. (Although this effect is limited, as the government avoided important inputs that businesses use.) Factoring in these cascading effects, the overall consumer price impact could be around 0.6 percent.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Some items will feel the impact more than others. For example, furniture tops the list, with potential price increases exceeding 2 percent, as about one-third of Canada’s furniture imports come from the U.S. Food prices, a particularly important category, could rise by approximately 1 percent. I display the top thirty affected categories of items below.

Canada needs a much better plan than retaliatory tariffs

By Ian Lee, associate professor, corporate and business strategy at Carleton University

The geopolitical strategist Henry Kissinger taught us it is the role of the national leadership of a country to recognize, articulate, and vigorously defend vital national interests.

The events of the past three months in Washington and Ottawa reveal the failure of Canada’s national leadership to recognize—let alone understand—Canada’s national strategic interests.

Canada’s strategic response must not be emotionally driven, ad hoc, retaliatory tariffs against the largest economy in the world, representing 25 percent of total world GDP, by a declining middle power one-tenth its size.

The strategic end game for Canada can only be the removal of all tariffs between Canada and the U.S. and full and free access to both economies.

This can only be accomplished via a treaty that is far more than CUSMA 2.0. It must be a comprehensive treaty between Canada and the U.S. that will include rules concerning illegal immigration, illegal drugs, illegal guns, defence spending, protected industries, taxation, and open access to both economies.

Contrary to the repeated claims by Trudeau, Chretien, Freeland, Carney, and Ford, retaliatory tariffs will not cause Trump to back down. It has incited exactly the opposite response—yet ever more tariffs against Canada in a downward tariff doom loop for Canada.

Canada must focus on the comprehensive restructuring of the Canadian economy that involves a repudiation of the policy framework of the past half-century of subsidize, regulate, and protect.

Yes, as Ms. Rogers demonstrated, it is time to “break the glass.”